The four and a half centuries of inhabitation of Bermuda have seen its treacherous reefs bear witness to countless shipwrecks. Shipwrecks became such a common occurrence in the region that it gave life to legends of the Bermuda Triangle and the very strange occurrences there. The English brigantine merchant ship known as the Caesar suffered a similar fate as countless ships before it. However, the fascination of this relatively common ship was the unique cargo it carried.

When the Caesar sank on 17 May 1818 after wrecking on a reef, it would the first of six merchantmen to be lost in Bermuda that year. (Marx 1987:309) The Caesar had been en-route to Baltimore, Maryland from Shields, Newcastle, England when it met its demise. The brig had been built in the town of Cumberland, County Durham in 1814 during the War of 1812. There is debate in academic circles whether Caesar was a brig or brigantine as different sources describe it as one or the other. Unfortunately, because the ship was so heavily salvaged immediately following its sinking, and given the minute difference between the designs, for the purpose of this research the two terms will be used interchangeably.

While underway towards Baltimore from Shields Caesar was sailed under a Captain James Richardson and a crew compliment of seven. A mention of the ship’s demise is found in Lloyd’s List from 3 July 1818. “The Caesar, Richardson, of and from Newcastle to Baltimore, was lost on a reef of rocks off the west end of Bermuda, on 17th May. Part of the Cargo saved with damage. Spars, rigging, etc. also saved.” There is no indication one way or the other from the report, that Captain Richardson or any of the crew survived. It should be noted however, that referring to other ships lost in the area within the same marine list, Lloyd’s List does indicate whether a crew was saved or not. This would imply; and considering the physical location of the wreck; that the crew did not survive.

The wreck was forgotten about to some degree though its physical evidence remained in the private heirlooms of Bermudans. The ship itself sits in 25 to 35 feet of water with only un-salvaged cargo and some hull remains intact. The ship’s physical location being 32°15’33.55″N, 64°58’54.12″W, it lays only a short distance southwest from Hog Bay Park on the southwest shore of the island of Bermuda. It was not until Teddy Tucker rediscovered the wreck in 1957 that several mysteries were solved regarding the Caesar.

According to Daniel Berg, when the ship went down it was known to have been carrying a cargo that included grindstones, medicine, decorative flasks, grandfather clock parts, glassware, white, red, and black lead oxide, and a marble cornice intended for a church in Baltimore. (Berg & Berg, 1991:12) Teddy Tucker confirmed this cargo’s existence and was able to explain the presence of other strange artifacts found Bermudian’s homes with his 1957 salvage operation.

Flotsam and jetsam fom the Caesar was utilized almost immediately upon its sinking as is eluded to in the Lloyds of London report. It isn’t unreasonable to presume what was left of its mast and rigging fell into the hands of Bermudians for construction material. The Bermudan Department of Environment and Natural Resources somewhat supports this assertion. They claim that many of the older docks in the west end have materials unique to the Caesar either on them or as part of their construction.

During Teddy Tucker’s salvage operation of the Caesar’s remains in 1957, he was able to recover such a significant yield of artifacts, that many were utilized in construction projects in Bermuda. Over 500 bricks were salvaged and utilized in the renovation of the old Rum Runners building, while the recovered grindstones were used to make walkways at several hotels and private residence. (Bermuda Department of Environment and Natural Resources) Even now, divers frequently find artifacts in Caesar’s final resting place in the 35 ft. sand hole. The remaining wooden hull beams are reported to appear towards the end of the winter season or on occasions where passing hurricanes stir up the sand that typically buries the timbers.

Intricately decorated 19th century masonic flasks were found passed down from island families with little to no explanation of how they came by them beyond a generic referral to a shipwreck. Masonic lodges had been present on the island since the late 18th century, but what made the flasks unlikely to have been related was the presence of American iconography on the flasks. Teddy Tucker’s rediscovery of Caesar in 1957 and its cargo confirmed that the masonic flasks in possession of the islanders. A significant question remains as to why there were such an abundance of masonic flasks present on the ship. The unique design of the flask present within the Bermuda Maritime collection an answer for at least part of the question. Several distinct markings as well as the bottles’ general appearance at least pinpoint the origination of the flasks. All combined, it creates a narrative by which someone could know where the flasks started, and their various intended destinations. The flasks would not have been a typical commodity for the average person as they were meant specifically for master masons in the various freemason lodges in the United States.

According to a conversation with Dr. Rouja, Teddy Tucker believed the flasks were being brought back from England after an important transatlantic lodge meeting. The lodge meeting would have been the first of their kind following the cessation of hostilities between the two nations after the War of 1812. Mr. Tucker believed that the flasks may have been specially made for the reunification meeting and brought back as commemorative pieces. To date no research has been done on why the masonic flasks were on the ship, and it stands to reason something important to the fraternity was occurring in England. The other possibility is that the flasks were owned by the crewmembers themselves. If this is the case, then it would be possible to positively identify them as their respective masonic lodges would have held memorial for them that would have been entered into the lodge archives.

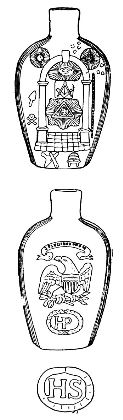

The masonic flask was part of the artifact collection that resulted from Teddy Tucker’s salvage of Caesar. This particular flask is a medium olive amber color and has several markings indication that it was affiliated with the Master Mason Degree of Freemasonry. Figure 2 has been included as a method for comparison. The time spent underwater wore away the legibility of some of the designs seen on figure 2. The designs on both flasks are derived from the Keene-Marlboro-Street Glassworks that existed from 1815 until 1850 in Keene, New Hampshire.

Starting from the top left corner to the type right is a sun moon and stars that serve as an allusion to the heavens in freemasonry. Immediately below this is an archway alluding to the entrance of a temple. Within the archway at the very top is the all-seeing eye though not readily visible on the recovered artifact due to erosion. Beginning again from the left side is a trowel representing the cement of brotherly love and affection that unites masons into one sacred band(Bahnson, 1892:56). To the right of the trowel is a depiction of a Holy Bible laying beneath a square and compass. At the next level is skull and crossbones that alludes to man’s mortality. Adjacent to the skull and crossbones is the letter G alluding to geometry. Finally, at the very bottom is a depiction of a set of stairs leading to a porch with a plum-line, level, and beehive beneath it.

The uniqueness of the recovered flask’s design allowed it to be positively identified as having come from the glassworks in Keene, NH. Experts have placed the Caesar’s recovered flasks as having been made in 1815. (McKearin & Wilson 1978:103,438) The maker’s mark of Henry Schoolcraft present on the bottom of the recovered flask was a further clue, as it meant the flask could have been made no further than February 1817. Schoolcraft made the masonic flasks with his mark on the bottom at the Keene Glass Words while he was part-owner from 1815 until 1817. Further research with the Grand Lodge of New Hampshire and the Grand Lodge of England is ongoing to determine if there is any mention of this shipment in the Masonic Archives.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bermuda 100. http://bermuda100.ucsd.edu/caeser/index.php

Bahnson, Charles F.

1945 North Carolina Lodge Manual: for the Degrees of Entered Apprentice, Fellow Craft, and Master Mason, as Authorized by the Grand Lodge of North Carolina Ancient Free and Accepted Masons; and the Services for the Burial of the Dead of the Fraternity. Grand Lodge of North Carolina, Raleigh, NC

Berg, Daniel, and Denise Berg

1991 Bermuda Shipwrecks: a Vacationing Divers Guide to Bermudas Shipwrecks. Aqua Explorers, East Rockaway, NY

Ceasar.

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Bermuda Department of Environment and Natural Resources. https://environment.bm/ceasar/

Lloyd’s List. 1817-1818.

HathiTrust. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015005778173;view

Lockhard, Bill, Beau Schriever, Bill Lindsey, and Carol Serr

Keene-Marlboro-Street Glassworks. Society for Historical Archaeology

Marx, Robert F.

1987 Shipwrecks in the Americas. Dover Publications, New York

McKearin, Helen, and Kenneth M. Wilson

1978 American Bottles and Flasks and Their Ancestry. 1st edition. Crown