Before diving into North Carolina’s Civil War Iron Clads, it is important to understand the development of steam vessel construction in North Carolina. Still and Stephenson calls 1816 to 1860 the “golden age of the river steamboat” in North Carolina (Still and Stephenson 2021:84).

In 1818, the New Bern Steamboat Company bought the Virginia-built steamer Norfolk to connect New Bern with the coastal cities and river towns (Barfield and Norris 2006). Two of the earliest North Carolina-built steamboats were Henrietta and Prometheus. Henrietta, launched in 1818 at Fayetteville, was a 100-foot side-wheeler that served on the Cape Fear River between Fayetteville and Wilmington. Built by War of 1812 hero Otway Burns in Beaufort, North Carolina, Prometheus linked Wilmington and Smithville (now Southport) on the Lower Cape Fear. President James Monroe traveled between Wilmington and Smithville on the Prometheus during his Southern Tour of 1819 (Barfield and Norris 2006).

(from https://www.ncpedia.org/steamboats)

North Carolina’s watery transportation routes depended on steam dredges to remain open year-round. The first successful steam dredge built in North Carolina was built with machinery from New York in 1826 (Still and Stephenson 2021:91, 92).

Steamboat design in North Carolina was flexible and reflected the needs of the local waterways as well as the purpose for which each steamboat was built. The need to navigate shallow rivers and sounds led to a flat-bottomed, box-like design like western riverboats. However, because the rivers of North Carolina were narrower than the rivers out west, the state’s steamboats usually had a narrower beam, as well. Sidewheel steamboats were twice as common as sternwheelers, with the downside that the broader sidewheelers could not navigate as far upriver (Still and Stephenson 2021:84-87).

Additional rudders were a common feature on North Carolina steamboats. By the 1850s, most steamboats had three rudders. Some steamboats, like Wayne II of New Bern (1848) had rudders fore and aft for responsive navigation on narrow, winding rivers (Still and Stephenson 2021:87).

Although trains grew in importance in the years before the Civil War, transportation on North Carolina’s Atlantic coast, sounds, and rivers still depended on ferries and steamboats (Still and Stephenson 2021: 90-91). The 1860 Wilmington-built ferry, Clarendon, incorporated railroad tracks on its deck to ferry trains across the Cape Fear (Still and Stephenson 221:91).

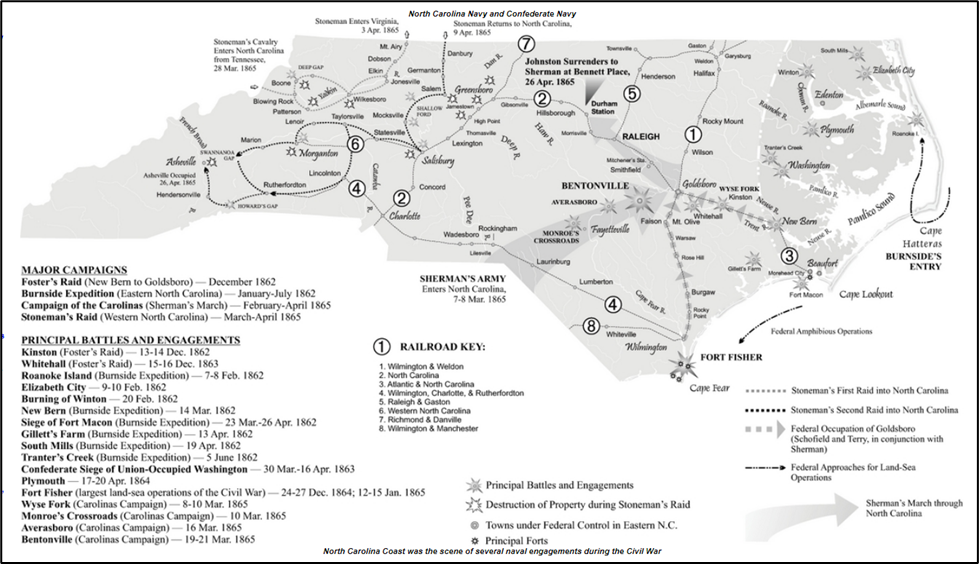

Soon after the start of the Civil War, General Burnside successfully lodged Union troops in the Albemarle region. Then, the U.S. Navy’s “Anaconda Plan” blockade tightened along the Southern coastlines. North Carolina desperately needed the Confederate Navy to defend against this Union onslaught (Duppstadt).

(from http://www.thomaslegion.net/north_carolina_and_the_confederate_states_navy.html)

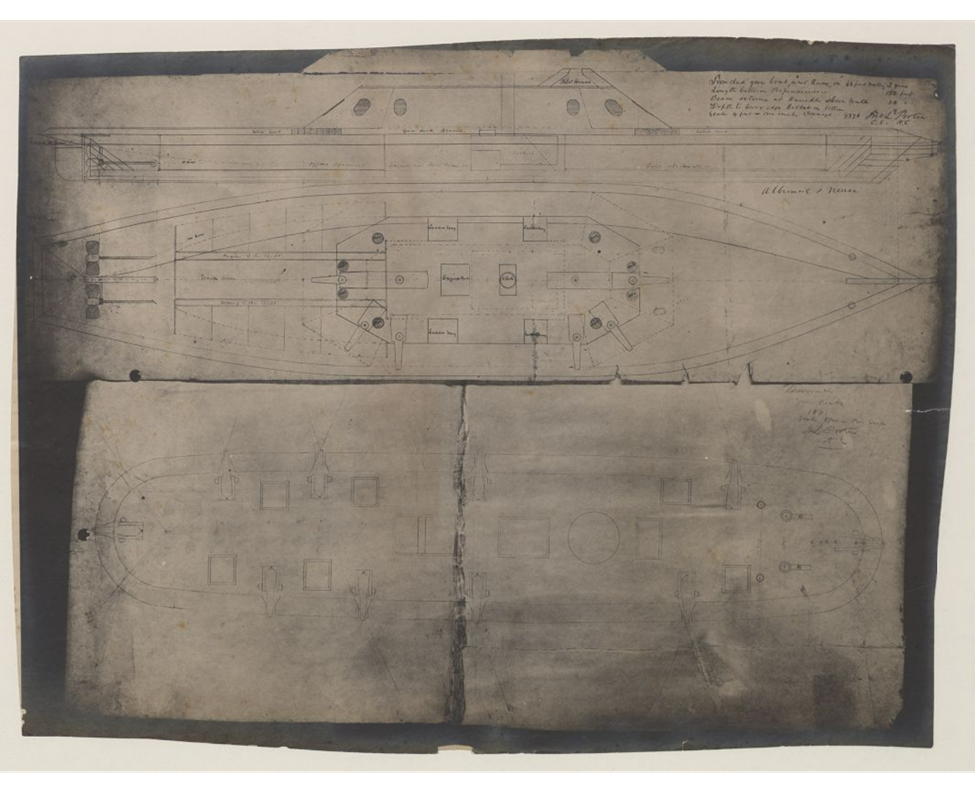

The Confederate Secretary of the Navy, Stephen Mallory, dispatched John Porter (the man who designed CSS Virginia) to North Carolina to supervise the construction of CSS Albemarle in 1862. Internecine squabbles in the Confederate Department of the Navy and a critical shortage of iron delayed the ironclad’s construction. Built in a cornfield near Edward’s Ferry, CSS Albemarle began its maiden voyage in early 864 with shipwrights and blacksmiths still hammering its casemates into place as she steamed down the Roanoke River (Trotter 1989:234-237).

East Carolina University Digital Collections (from https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/4496)

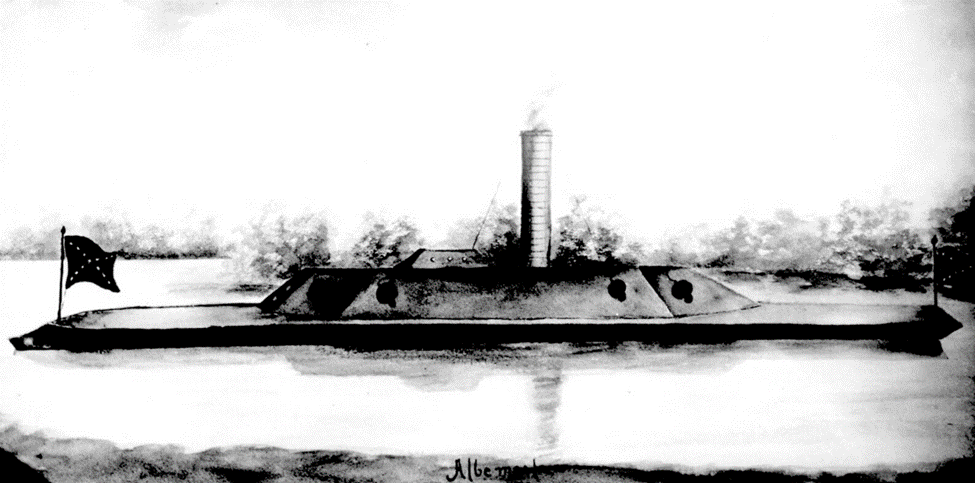

Although her naval career was short, her career was spectacular. CSS Albemarle was the most successful North Carolina ironclad. In April 1864, CSS Albemarle helped Confederate forces recapture Plymouth by sinking USS Southfield and driving away the other Union gunboats In her second battle, this time on the Albemarle sound, she drove off seven Union warships trying to enter the Albemarle. CSS Albemarle met her end at the hands of a Union torpedo boat on 27 October 1964 (Duppstadt).

(from https://www.flickr.com/photos/north-carolina-state-archives/4290829322/in/photostream/)

CSS Albemarle Van Tour – YouTube

The Washington County Historical Society and the Port o’ Plymouth Museum preserve and celebrate the history Washington County with a special focus on the CSS Albemarle. The museum is home to a working replica of the ironclad and is rated one of the “Top 10 Civil War Sites in Carolinas” (Charlotte Observer as quoted by the Port o’ Plymouth Museum).

(from https://portoplymouthmuseum.org/about-port-o-plymouth-museum/)

Although Albemarle’s sister ship CSS Neuse had a less significant combat career than the Albemarle, it is historically more significant. The crew intentionally burned CSS Neuse after she engaged advancing Union cavalry along the Neuse River on 12 March 1865. Her armor and machinery were salvaged shortly after the war, but her wood hull was eventually covered by the river’s shifting sands (Bright 2006).

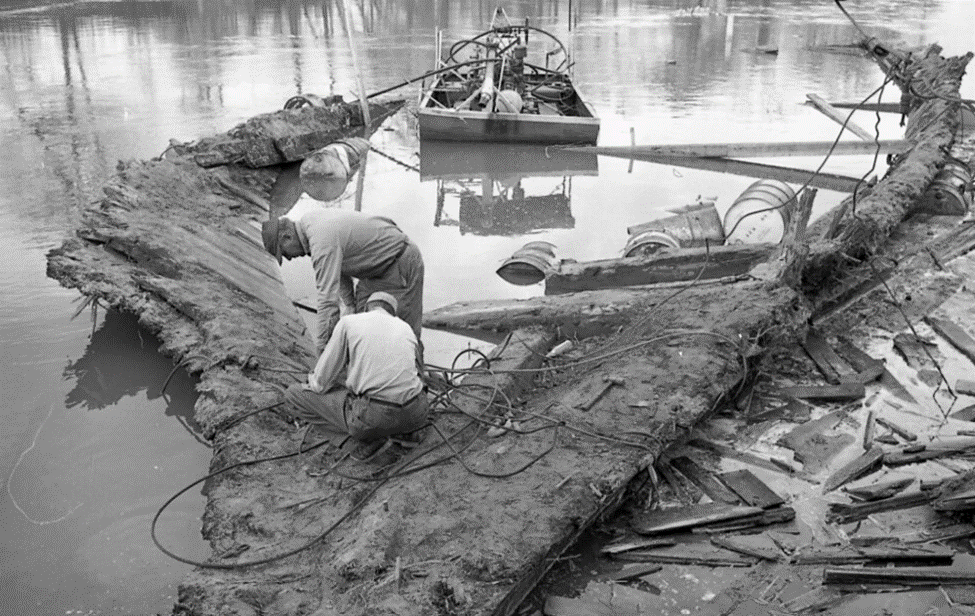

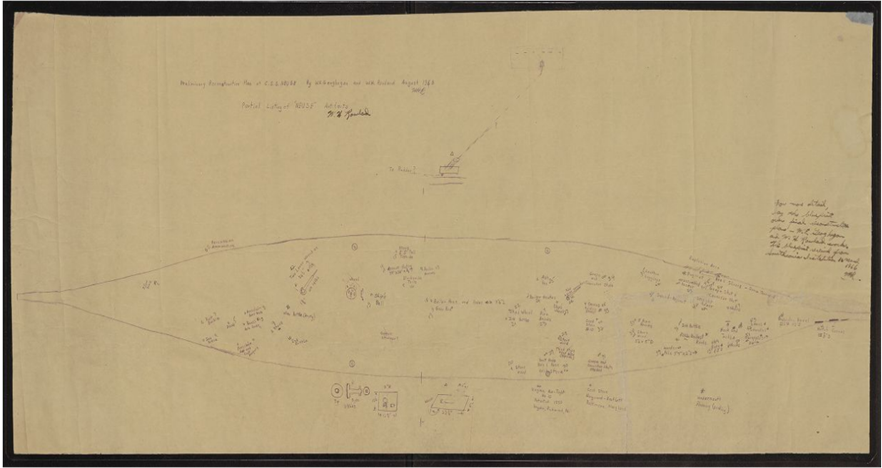

From 1961 to 1963, three citizen of Kinston salvaged CSS Neuse. She was displayed, along with many of her artifacts, at the CSS Neuse Historic Site in Kinston for decades before the CSS Neuse Civil War Interpretive Center opened. In the last decade, Master Shipbuilder Alton Ray Stapleford built a replica of the CSS Neuse that is also open for visitors in Kinston (CSS Neuse).

(from https://www.flickr.com/photos/ncculture/7368825482/in/album-72157630057463415/)

An Overview of the CSS Neuse – YouTube

Special Note:

There were two other North Carolina ironclads not mentioned in this article, CSS Raleigh and CSS North Carolina. These two ironclads were built in Wilmington and served on the Cape Fear and near Fort Fisher. These two warships deserve to be covered by future research, possibly in combination with an article covering the naval actions around Wilmington and blockade runners.

North Carolina’s Mosquito Fleet and local supporting vessels such as Scuppernong, on Indiantown Creek in Currituck County should be topics of future research as well.

https://www.ncpedia.org/mosquito-fleet

References:

Anderson, Bern – 1962 – By Sea and by River, the Naval History of the Civil War. Da Capo Press, Perseus Books Group.

Barfield, Rodney D. and David A. Norris – 2006 – Steamboats. Encyclopedia of North Carolina. Edited by William S. Powell. University of North Carolina Press. https://www.ncpedia.org/steamboats

Blair, Dan – 2006 – Albemarle, CSS. Encyclopedia of North Carolina. Edited by William S. Powell. University of North Carolina Press. https://www.ncpedia.org/albemarle-css

Bright, Leslie S. – 2006 – Neuse, CSS. Encyclopedia of North Carolina. Edited by William S. Powell. University of North Carolina Press. https://www.ncpedia.org/neuse-css

Canney, Donald L. – 2015 – The Confederate Steam Navy 1861 – 1865. Schiffer Publishing Ltd. Atglen, Pennsylvania.

CSS Neuse – The Story of the CSS Neuse. CSS Neuse Civil War Interpretive Center. https://cssneuse.org/about/history/

Duppstadt, Andrew. Confederate States Navy (in North Carolina). North Carolina History Project.

Still Jr., William N. – 1988 – Iron Afloat: the Story of the Confederate Ironclads. University of South Carolina Press

Trotter, William R. – 1989 – Ironclads and Columbiads. John F. Blair, publisher, Winston – Salem, North Carolina.

Additional References:

N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources

Salvage of the CSS Neuse from the Muck | NC DNCR (ncdcr.gov)

NC Business History — 19th Century Steamboats in North Carolina (Alphabetic List) (historync.org)

North Carolina and the Confederate States Navy (thomaslegion.net)

Museum – CSS Neuse Civil War Interpretive Center – Kinston, NC