“Dugout canoes dating back to 3095 BC have been found in the pocosin lakes at the center of the Albemarle peninsula. Nearly five thousand years later, dugouts of the same time-tested design were still being used here. When the Roanoke colonists arrived in 1584, the native Algonquins were described as exceptionally skilled watermen who routinely crossed the precarious Albemarle and Pamlico sounds in large dugouts.” [Roy T. Sawyer in America’s Wetland: An Environmental and Cultural History of Tidewater Virginia and North Carolina 2010, pg. 102]

The first boatbuilders in the region were the natives who used dugout canoes in their daily lives on the waterways and coastlines of pre-contact North Carolina as described by Sawyer in the quote above. The earliest colonists were almost certainly boat and canoe builders, if not shipbuilders, from the earliest days of the colony. They needed canoes and small sailing craft for transportation. However, very few records exist to prove that point. The first vessel recorded by English naval authorities, James of Virginia, was completed in 1688 (Stills and Stephenson 2021:24). One of the earliest known shipbuilders was Thomas Harding of Bath. Harding built a 46-foot sloop for Governor Thomas Cary in 1706 (Stick and Fontenoy 2006).

In his 1936 book, The Commerce of North Carolina1763-1789, Charles Crittenden describes the small watercraft built locally in colonial North Carolina as a mixture of canoes, perriaugers, scows, flats, yawls, small sloops, and lumber rafts (Crittenden 1932:15-18).

The typical tonnage of commercial vessels, by type, operating in North Carolina waters at that time were:

Sloop – under 50 tons, sometimes as little as 6-8 tons

Schooner – under 50 tons

Brig/brigantine – avg. 100 ton

Snow – avg 150 tons

Ship – avg 150 tons (Crittenden 1936:9,10)

Crittenden lists the number and total tonnage of vessels built in North Carolina from 1769 to 1772 as:

Year Number Tonnage

1769 12 607

1770 5 125

1771 8 241

He goes on to state that, according to Port Roanoke records for 1772, twenty-one of the one hundred and forty-six ships arriving or departing from the port were built in North Carolina. These North Carolina-built vessels accounted for 1070 of the 6304 total tons reported (Crittenden 1936:13).

Authors William Still and Richard Stephenson describe how colonial North Carolina boatbuilders and shipbuilders constructed their vessels to meet specific local needs rather than larger economic factors. This stands in contrast to the focus, in New England, on the Atlantic fisheries and commerce with Great Britain (Still and Stephenson 2021:8,9). Still and Stephenson also describe the paucity of colonial-era shipbuilding and shipyard records for North Carolina. Road and place names, local traditions and oral accounts, newspaper articles, deeds, wills, tax records, and more all mention shipyards, boatyards, and boathouses. However, they rarely describe the facility or its location. This makes it almost impossible to determine exactly how many shipyards existed in North Carolina before the 1900s (Still and Stephenson 2021:9).

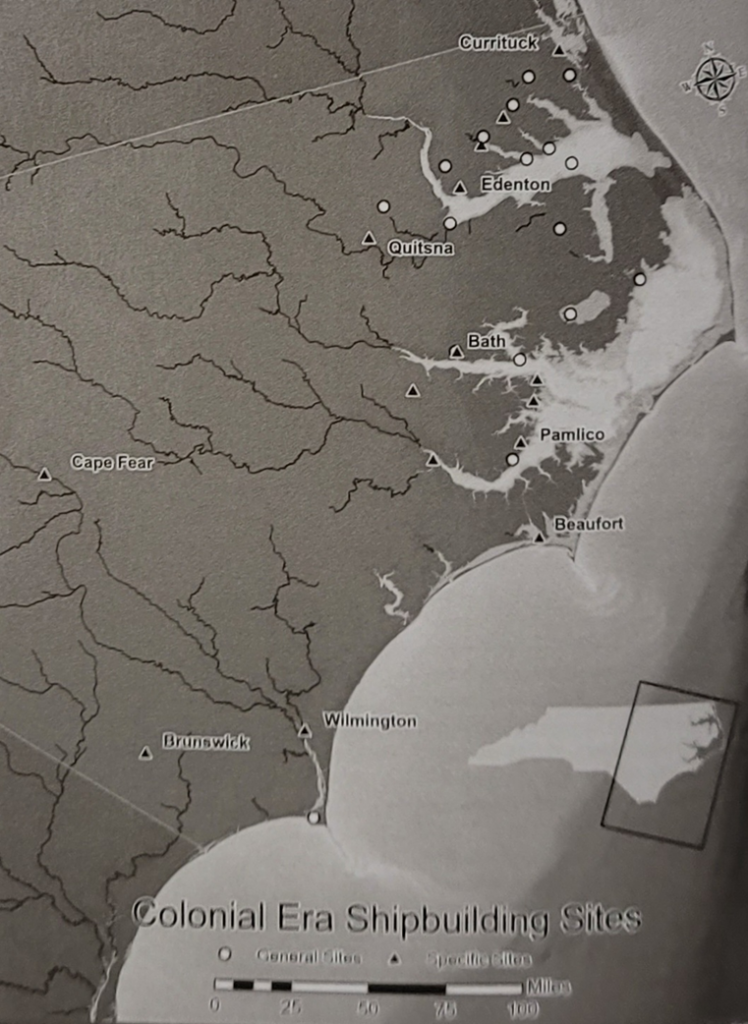

The greatest density of North Carolina’s colonial shipyards was around the Albemarle region, growing scarcer the further south one looks, as seen on the following map (Stills and Stephenson 2021:36):

Another problem in identifying early colonial era shipyards was the ad hoc nature of many of these shipyards. Rather than established facilities with purpose-built buildings and services, North Carolina’s shipyards were often just a clearing near water and timber. Some of them were used over long periods of time, but many were used for building just one specific vessel (Still and Stephenson 2021:9).

Although the home-grown, informal characteristics of North Carolina’s boat-building industry remained relatively unchanged up to the early to mid-1900s (Still and Stephenson 2021:9), established shipyards began to take shape in the early 1700s. for example, Josiah Grainger of Wilmington set up a shipyard at the bottom of Church Street. This location continued in use as a shipyard, by a succession of owners, all the way to the twentieth century (Still and Stephenson 2021:30).

One of colonial North Carolina’s well-established shipbuilders was Thomas McKnight, who came to North Carolina from Scotland. Buying property in Currituck County, McKnight built a successful shingle mill, a large plantation, and a shipyard complete with wharves and warehouses on the banks of the North River (Still and Stephenson 2021:30-32). McKnight claimed his shipyard was the best and “and most commodious” shipyard “in the province” (Still and Stephenson 2021:31). This shipyard was large enough for McKnight to launch vessels of at least 100 feet in length. He could also careen his vessels at this yard. His businesses owned and operated at least four vessels at the beginning of the American Revolution. It appears there was another vessel under construction in the yard at the outbreak of the Revolution. (Still and Stephenson 2021:31).

McKnight’s shipyard and other businesses were seized when McKnight abandoned the General Assembly during deliberations over declaring independence from Great Britain. McKnight returned to Great Britain after escaping from the colonies (Still and Stephenson 2021:31-32). Much of what is known about his career in North Carolina comes from his appeals to the British government to compensate him for the property he lost in Currituck County. These documents are available in the North Carolina State Archives.

The story of Thomas McKnight and his shipyard deserves better research and development than fits in the scope of this article.

See Also:

References:

Crittenden, Charles Christopher – 1936 – The Commerce of North Carolina 1763-1789. Yale University Press,

Sawyer, Roy T. – 2010 – America’s Wetland: An Environmental and Cultural History of Tidewater Virginia and North Carolina. University of Virginia Press.

Stick, David and Fontenoy, Paul E – 2006 – Shipbuilding. Encyclopedia of North Carolina. Edited by William S. Powell. University of North Carolina Press. https://www.ncpedia.org/shipbuilding

Still Jr., William N. and Richard A. Stephenson – 2021 – Shipbuilding in North Carolina 1688 – 1918. The North Carolina Office of Archives and History. Distributed by the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.