Hunting for Sport:

The History and Archaeology of Waterfowl Blinds in Currituck County, North Carolina

THESIS PROSPECTUS PREPARED FOR THE PROGRAM IN MARITIME STUDIES, DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY

EAST CAROLINA UNIVERSITY

Emily Steedman

Master’s Candidate

Program in Maritime Studies, East Carolina University

14 April 2014

Abstract

History has suggested that a change in waterfowl hunting methods/technologies occurred in Currituck Sound, North Carolina, after the passage of the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. The use of sinkboxes and market hunting was gradually replaced by a new system of guided/sport hunting. This system included the use of outboard motor vessels, shoving skiffs, and, of particular interest, duck blinds. The blinds were adapted not only to fit the Currituck Sound landscape, but also to accommodate guided hunting parties. Blinds were necessary to the success of sport hunting. Moreover, the blind’s design and construction reflected adaptations to and adoption of new technologies, resource opportunities, and changing social behavior in the region. An analysis of the history and archaeology of waterfowl blinds in Currituck Sound will demonstrate their significance in the history of waterfowling.

Introduction

Waterfowl hunting, or the shooting of ducks and geese for market or sport, has existed for many years as an economic and recreational activity. It was a significant source of income for many individuals during the nineteenth- and twentieth-centuries in many states, but this thesis aims to examine its presence in Currituck Sound, North Carolina (Figure 1), after the passage of Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, from approximately 1920 to 1970 (United States Congress 1918:755-7). 1970 acts as a logical cut-off point for the study because it was during this decade that the county’s industry shifted from waterfowl hunting to commercial real estate development. Particularly, the land around Corolla saw an explosive increase in development; in addition, increased activity in the conservation movement at this time limited waterfowl hunting (Davis 2004: 119-128). Consequently, this study aims to analyze blinds during their greatest period of use, the 1920-1970 time frame. Currituck Sound was chosen as the location for this study because it has a well-defined history of waterfowl hunting and its community has a strong connection to its waterfowling past. Waterfowling in this region was an industry whose form and economy evolved with the introduction of, and adaptation to, new technologies, resource opportunity, and changes in societal behavior and attitudes towards the industry. This thesis proposes to examine the construction and use of waterfowl blinds during this time period and understand how they influenced and were influenced by the region’s economic, social, and geographic landscape. Moreover, a study of the region’s waterfowl blinds provides an opportunity to look at waterfowl hunting through an archaeological lens and examine the complex relationships between humans, material culture, and the environment. The first step in understanding this relationship is understanding the history of waterfowling in general.

Historical Background

The history of waterfowling largely focuses on technical changes as a series of technological advancements. The evolution of gun design, in particular, was one of the most important technological improvements for waterfowl hunters. The transition from the hammerless breechloader to Browning’s automatic shotgun led to the crowning period in market hunting. This was not the only gun technology to bring profit to hunters. The big gun, pipe gun, and battery guns were all created/adapted to fill the needs of the waterfowl hunter. The skill of the hunter in bagging game with these tools was legendary, and, oftentimes, highly exaggerated. Still, it was not unusual for a hunter to return at the end of the day/night with thirty ducks and anywhere from eight to ten geese (Walsh 2008:25, 89, 115-117).

However, despite the importance of guns in waterfowling, they were not the only equipment that was important to the industry’s success. The boats used in waterfowl hunting also needed to fit market and sport hunter requirements. Initially, while there was a range of vernacular watercraft to fill this role, the most prevalent was the sinkbox (Figure 2). Sinkboxes looked like coffins in their construction, and were designed for only one or two people. Their shape was specifically suited to camouflage the hunters. The boat was flat-bottomed and could be sunk until it was flush to the water (Walsh 2008:136). This made it perfect for hunters to hide from their prey.

The individuals who hunted the Outer Banks of North Carolina were especially adept at using the sinkbox (or battery), and actually helped prove its efficiency in hunting waterfowl. They started the practice of tying sinkboxes together to make them more attractive, and discovered that using larger decoys helped hide the boxes better (Walsh 2008: 137). Sinkboxes represented the pinnacle of design during the era of market hunting. Their construction allowed the market hunting industry to flourish, making the significance of their place in waterfowling absolute.

The inception of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 brought changes to waterfowl hunting technologies and techniques; sinkboxes were prohibited, along with the use of corn as bait (Currituck Chamber of Commerce 2000:6). These restrictions led to the need for a new dominant system of waterfowling: sport hunting. Waterfowl blinds played an important role in this form of hunting. At first glance, these blinds appeared as little more than roughly constructed camouflage hideouts. However, much more thought went into their creation than first appeared. The hunter had to consider what type of waterfowl he wanted to hunt, and then set up a blind whose construction and placement were based on that bird’s feeding habits (Walsh 2008:7). There was no single blind design or location that worked for hunting types of waterfowl; however, there does exist a general description of their construction. Blinds were usually built on a point of marsh. Long poles were driven into the ground, then lathes were nailed to the inside of the poles to hold the floor. Lathes were then nailed to the outside of the poles for erecting the framing. Lastly, sedge was cut from the marsh and attached to the blind to act as camouflage and insulation. Blinds provided much more space for hunters and their equipment. There was a bench for them to sit on, and a narrow shelf that was used to hold small items like duck calls and shotgun shells (Morris 2011:91). A variety of blind designs were used, including marsh blinds, open water blinds, and even blinds that could be removed and placed at another location (float blinds) (Walsh 2008:7). They were diverse and versatile instruments that offered the market hunter a different and profitable way to make money/bag game.

That was not to say that sport hunting did not exist prior to the 1918 Act. North Carolina, in fact, was primed to support this style of hunting. Sport hunting in Currituck Sound dated back to the 1850s with the establishment of the Currituck Club. Yet, after the passage of the 1918 Act and the subsequent decline of commercial hunting, sport hunting emerged as the dominant form of waterfowling in Currituck Sound, North Carolina. It was for this type of business that waterfowl blinds were especially appropriate. William Wright, a hunting guide from Currituck County, stated that blinds were not widely used in the area until after the 1918 Act. He remarked that, “… back then (pre-1918) they used sinkboxes (for market hunting). Now that was some hunting. Shoot all you wanted” (Morris 2011:95, 98-99). Blinds were the next big thing in the industry, and emerged as market gunners transitioned into hunting guides.

Blinds worked with boats to provide the whole experience to the sport hunter. A gas boat ferried sport hunters out to the blinds where, usually, two men were placed in a blind with their guide in a skiff. The motor boats and skiffs were shallow draft vessels that could navigate the shallow waters of Currituck Sound. Once hunters were situated in the blinds, the men would shoot the waterfowl, and the guide would pole out in the skiff to pick them up. At the end of the day, hunters were picked up and returned to their respective hunt clubs while the guides dressed and iced down the day’s catch for its trip home with the hunters (Morris 2011:95-6). This was the new way of life for the market-hunter-turned-hunting-guide. He led paying individuals to good hunting locations for them to shoot, while handling the not-so-glamorous side of hunting (retrieving, cleaning, and dressing game). Waterfowl hunting had evolved. It began as a market industry that also attracted sport hunters, and later became a sport-centered business in which commercial hunters acted as paid guides for the economic elite. It was in this new era of hunting for sport that duck blinds emerged as a key tool in the arsenal of the waterfowl guide and sportsman.

Research Questions

The major focus of research for this project will be on the construction and use of waterfowl blinds in Currituck Sound, North Carolina, during which time guided hunting parties reigned supreme, roughly 1920-1970. Preliminary research on this topic has suggested that duck blinds were constructed differently to fit their surroundings. The major research question to be addressed is:

- How is the process of adapting to the changing anthropogenic and environmental conditions of waterfowl hunting represented in the historical and archaeological record?

Other, secondary questions include:

- How were blinds in Currituck Sound constructed? What materials were used and who built them? Where did these materials come from, and how did they affect/shape the region’s environment?

- Where were blinds constructed and why were they constructed in those places? Are certain areas better suited for the placement of blinds than others?

- Are there differences in the construction techniques and features of marsh versus open water versus portable blinds? If so, why?

- Do the blinds change through time?

- How far apart were blinds spaced? How much did human decision-making versus the natural topography of the land affect their placement?

Tertiary questions include:

- When did hunting in Currituck Sound transition from market to sport hunting?

- Did market hunters use blinds before or after the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918? What factors affected their use/non-use?

- How were skiffs used in sport hunting? What features made them ideal for this type of industry?

- How were motor boats used in sport hunting? How were they adapted to fit this industry?

- How did the guided hunting industry work in Currituck Sound? Where did the guides and sportsmen stay while hunting?

- What type of waterfowl were the most popular to hunt? How did this affect blind construction and placement?

- What other technologies (guns, boats) might have affected the shape/location of blinds? Or, how were these technologies adapted to work in blinds?

These questions are important in understanding the development and use of blinds and boats in waterfowl hunting. Blinds and boats were important tools that have been overlooked because of public interest in other technologies, mainly guns and sinkboxes. These technologies have taken center-stage because of their association with illegal market hunting, a subject that has attracted much interest over the years (see Walsh 2008). This project is attempting to provide an archaeological analysis of waterfowl blinds, placing their use and importance within the context of the industry as a whole.

Theoretical Approach

The major theoretical approach for this project is a cultural ecology perspective. This theory was first associated with Julian Steward, and is generally explained as the study of the environment and how people adapted to it and how people changed their environment (Steward 1955:5; Hirst 2013). This means that the technological innovations produced by a group/society are shaped by the physical environment in which they live. This theory was later adapted by Karl Butzer into its modern form. He argued that archaeological sites, specifically adaptive systems, should be studied as part of and in relation to the human ecosystem (Butzer 1980:419). The human ecosystem, Butzer further explained, is made up of five themes:

- Space (topography and climate)

- Scale – (the size and shape of objects and aggregates in the environment)

- Complexity

- Interaction – (how humans interact with each other and the non-human environment)

- Stability – (focuses on the readjustment of adaptive systems for either short- or long-term ends) (Butzer 1980:419)

It is by analyzing these themes within the context of archaeological sites that an accurate understanding of past structures and systems can be understood. Butzer also created a model that placed an adaptive system (such as a vernacular ship) into three categories of creation and development: technology, resource opportunity, and social behavior (Butzer 1982:286). He published this theory in an article on the agricultural systems of Mesoamerica, arguing that the techniques and technologies used in the pre-Contact era were damaging to the environment in which they were applied (Butzer 1996:141-2). A maritime archaeological example of an adaptive system would be vernacular watercraft like riverboats whose draft is determined in accordance with the depth of the water it operates in. At the same time, the river boat can keep shallow water channels open by churning up/through sandbars. If an adaptive system is studied and understood within these classifications, then an accurate analysis of their archaeological and historical significance can be articulated.

If the blinds used by sport hunters are accepted as an adaptive system (and thus applicable to cultural ecology theory), then the technology involved in their construction includes: the structures’ designs, their pieces and construction, new technological developments, and how these pieces of technology interact with each other and the land/water they are built for. Resource opportunities would include the construction materials available for building blinds and boats as well as the processes that contributed to their creation/maintenance (such as topography, climate, storms, and ice). As an example, blinds were initially built using wood boards, but eventually switched to plywood because it was faster to build with and kept the wind out better (Morris 2011:91). Lastly, the social behavior that contributed to blind construction and use would include aspects such as the rise of sport hunting and the outlawing of market hunting. All these forces worked together to influence the role and importance of blinds in the Currituck region.

Another theory that is pertinent to this study is that of maritime landscape archaeology. The term was first coined by Christer Westerdahl, an associate professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. He defined the theory as, “the network of sea routes and harbors, indicated both above and under water” (Westerdahl 2011:735). Westerdahl further expanded upon this definition, stressing the need to study more than just shipwrecks; archaeologists also need to look at sources such as archival material, place-names, and historical documents, to name a few, in order to grasp the concept of a maritime cultural landscape (Westerdahl 2011:743). As this concept received more credibility in the maritime archaeology community, its definition evolved to mean: “human utilization of maritime space by boat: settlement, fishing, hunting, shipping, and, in historical times, its attendant subcultures, such as pilotage, and lighthouse and seamark maintenance” (Westerdahl 2011:745). In other words, maritime landscape theory deals with the study of human interaction with the water. This is a rather broad theoretical approach, and it can be used to discuss a wide range of topics.

One notable maritime cultural landscape study is Ben Ford’s discussion of archaeological sites located along the northeast shoreline of Lake Ontario. He argues that environmental, cultural, and political factors influenced the location of these sites through time, and also asserts that many sites have held continuous occupation from pre-Contact times to the present (Ford 2011:63-4).

Wayne Lusardi also employs the maritime cultural landscape approach to discuss the lumber and limestone industries of Thunder Bay in Wisconsin (Lusardi 2011:81-97). Although the examples provided deal with specific Great Lakes regions, the maritime cultural landscape approach is quite easily applied to any area where people interact with a water environment. It is extremely useful, therefore, for understanding the development of blinds in and along Currituck Sound.

Maritime landscape archaeology is ideal for the study of waterfowl blinds in Currituck County because these blinds were designed and placed, in part, based on the area’s landscape. For example, looking out at Currituck Sound from the Whalehead Club, one can see open water blinds dotting the waterfront. Marsh blinds were also built based on the curvature and shape of the land. It is possible, with further analysis, to argue that economic and social factors also influenced placement of blinds within the maritime landscape, in addition to the environment. Waterfowl blinds provide an excellent example of a different way humans have utilized maritime space that has been thus far overlooked.

Methodology

The methodology for this project is separated into three phases – the collation of archival material, the collection of archaeological material, and the analysis of both datasets via quantitative analyses (charts and graphs created in Microsoft Excel) and geographical information system (GIS) software (ESRI’s ArcGIS).

Historical Methodology

Historical research, in the form of the collation of published and unpublished maps, photographs, and reminiscences, is necessary before any field archaeology can be undertaken. The Outer Banks History Center in Manteo, North Carolina, should prove useful in collecting such historical data. The Center houses a variety of archival material, including historic photographs and maps. The Outer Banks Center for Wildlife Education in Corolla, North Carolina, should also provide pertinent primary and secondary resources, including photographs and an inventory list of blinds that may relate to this thesis. Travis Morris, a hunting guide who has utilized the blinds being analyzed, is also a potential resource for this project. Morris has many photographs in his personal collection that depict various aspects of hunting on the Sound during the 1960s and 1970s, and likely has reproductions of older photographs. Further potential photographic collections identified to date include:

- The Aycock Brown Collection (Outer Banks History Center, Manteo, North Carolina)

- Currituck Shooting Club Maps (Outer Banks History Center, Manteo, North Carolina)

- The Whalehead Club Photographic Collection (Whalehead Club, Corolla, North Carolina)

Other historical resources that deserve examination are the Currituck County Historical Society as well as The Whalehead Preservation Trust (WPT). While the sites adjacent to the Whalehead Club will be included, they will not be the only blinds examined. Nevertheless, the WPT may have documents and materials that directly relate to Whalehead’s history of sport hunting. These resources will help provide a thorough background on the history of Whalehead Club (Figure 3) and its participation in waterfowl hunting.

These resources might also reveal the location of duck blinds that have fallen into disrepair, and whose recording would prove invaluable in understanding the archaeology of duck blinds in Currituck Sound; these blinds would not have any modern modifications that might limit their significance. Located within these resources may also be information on the construction materials and technique. It is also acknowledged that other hunt clubs like Whalehead also existed during this time, and may provide additional information on the hunting practices and blinds of Currituck Sound.

There are several books to consult when learning about the history of waterfowling in Currituck. The first source is The Outlaw Gunner by Harry Walsh (originally published in 1971). This book is an excellent source of information on the different technologies involved in waterfowl hunting, although an emphasis is placed on those objects/artifacts that were made famous by illegal market hunters (Walsh 2008). Despite its limitations, it is an informative resource in understanding the waterfowl hunting industry. There are also several books written by Travis Morris, a native of Currituck County, which discuss duck hunting in the area and time period of intended study. Morris’s books are a good source of information on the process of guided hunts as well as the construction and maintenance of blinds. The books that appear the most informative are: Currituck as it Used to be, Untold Stories of Old Currituck Duck Clubs, and Duck Hunting on Currituck Sound: Tales from a Native Gunner (Morris 2006, 2010, 2011). The latter two, especially, delve into the history of hunt clubs in Currituck at a time when hunting guides often used duck blinds.

The other major book to consult is The Whalehead Club: Reflections of Currituck Heritage (Davis 2004). This book is an important resource because it delves into the history of one of several hunt clubs that existed in Currituck County, North Carolina. There are also other published sources that will be consulted in this research, whose information is provided in the preliminary bibliography.

Archaeological Methodology

Archaeological recording techniques are necessary for this thesis because they allow precise documentation of waterfowl blinds, which will allow description of individual blinds and comparison of sites. This documentation is vital in understanding how blinds are constructed; it will also help answer some primary and secondary project research questions. Moreover, their recording is important because it will document modifications to blinds and test assumptions about their construction and use. There are several facets to this project’s methodological approach. The framework for this project is inspired by a survey of abandoned vessels in the intertidal zone of the River Medway in Kent, England (Milne et al. 1998:2). The survey was designed to record as many near-shore hulks as possible with limited resources and time.

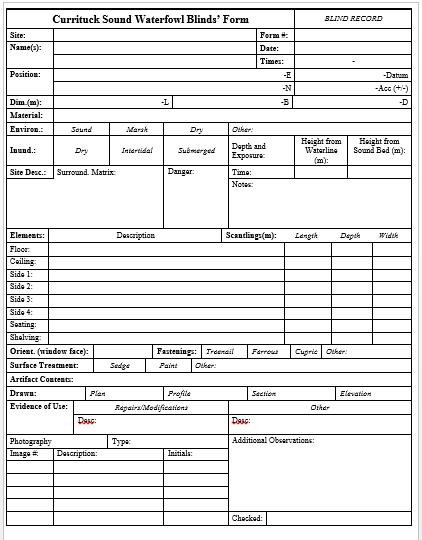

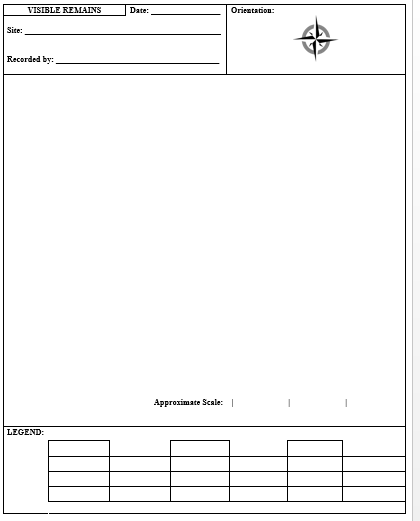

One key feature of this project was the use of a standardized form listing all key features to be recorded (Milne et al. 1998:54-7). A similar survey form document has been created to identify the major features of the blinds (see Figures 4-5). An initial reconnaissance survey of a site is necessary to establish a general orientation of the blind as well as to test the comprehensiveness of the survey form. After the reconaissance, a survey of the blinds will take place with the aid of volunteers from East Carolina University’s Program in Maritime Studies.

Blinds will be selected so that various environmental variables are represented. For example, blinds adjacent different banks of Currituck Sound will face dissimilar directions (N, S, E, W). By recording blinds adjacent to boat ramps and access points such as Corolla, Duck, Grandy, and Waterlily, it is anticipated that “mainland” versus “coastal” blinds can be examined.

In addition to the survey form, a journal will be kept that includes daily summaries of the blinds surveyed as well as detailed observations of the blinds and any other relevant data. Unmeasured and measured sketches of the blinds will also be drawn. Lastly, technical photography will be employed to acquire an accurate representation of blinds as well as to identify their key features. Using these methods, this project will identify patterns in Currituck Sound Blinds from a synchronic, diachronic, and geospatial perspective.

From visual observation alone, it is clear that there is a significant number of hunting blinds within Currituck Sound. While many abandoned, disused or relict blinds may lay underwater or adjacent currently used blinds, only above-water structures will be recorded due to financial and logistical reasons (no diving will occur). Consequently, because the extant blinds and historical research centers for this project are within driving distance of Greenville, the largest project expense will be the cost of gas (which will be covered independently). Local individuals will provide housing, and UNC-CSI will provide access to some equipment and office space. East Carolina University’s Program in Maritime Studies will also provide equipment for measuring and recording the hunting blinds. It is also likely that a boat will be required for recording the open-water blinds. A kayak or other small watercraft will be used in this case. The funds provided by the Currituck County Maritime Heritage Fellowship in 2013 will be used to fund the majority of the project.

Analysis

Technical photographs and detailed drawings obtained from field excursions will prompt enhancements to the data collected in the forms (for example, new observations regarding constructions trends). Data collected in the forms and any additional observations from the drawings, photographs and diarized observations will be transferred into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, allowing three methods of analysis to be employed:

- The sites database will be synchronically analyzed (i.e. atemporally across the dataset), by analyzing categories as pie charts. An example of this may be the categorization of the height of existing blinds. This will highlight tendencies in behavior, and will also provide transparency as to any collection bias in the dataset.

- The database of sites will be diachronically analyzed by looking at how elements of the blinds changed through time. Temporal data can be expressed in the form of bar and column charts to show when elements of construction or use may have been introduced, and how long they persisted for. An example of this might be distribution of sites with particular types or materials of fastener (i.e. a temporally diagnostic trait) across the study period, or the recurrent appearance of a form of material culture in the hunting blind.

- With the addition of spatial coordinates, the Excel spreadsheet becomes a geodatabase, which will allow for the geographical spread of sites to be imported into ESRI ArcGIS. The resulting geodatabase will also allow for geospatial patterns to be discerned and analyzed. Traits of blinds mentioned above (e.g. construction traits with temporal and non-temporal elements) can also be filtered to see if other geospatial trends emerge. GIS will also allow for the examination of other information that cannot be determined in the field, such as the distance of the blind from the nearest land, boat ramp, or settlement. Advanced geospatial analyses such as viewshed analyses, or density analyses may also allow for relationships between sites and the landscape to be revealed.

This three-tiered approach has the potential to illuminate behavioral patterns not discernible through a reading of the historical record alone, and may also highlight the interactions between humans and their environment. It is hoped that through this analysis that recognizable patterns in design and construction may be revealed and that potentially a typology of waterfowl blinds in Currituck Sound can be developed.

References Cited

Butzer, Karl W.

1980 Context in Archaeology: An Alternative Perspective. Journal of Field Archaeology. 7:417-22.

1982 Archaeology as Human Ecology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

1996 Ecology in the Long View: Settlement Histories, Agrosystemic Strategies, and Ecological Performance. Journal of Field Archaeology. 23:141-50.

Currituck Chamber of Commerce

2000 History of the Currituck Shooting Club. Currituck Chamber of Commerce, Currituck County, NC.

Davis, Susan Joy

2004 The Whalehead Club: Reflections of Currituck Heritage. Donning Company Publishers, Virginia Beach, VA.

Ford, Ben

2011 The Shoreline as a Bridge, Not a Boundary: Cognitive Maritime Landscapes of Lake Ontario, in Ben Ford (ed.) The Archaeology of Maritime Landscapes. p. 63-80, Springer Press, New York, NY.

Hirst, K. Krist

2013 “Cultural Ecology.” <http://archaeology.about.com/od/cterms/g/culturalecology.htm>Accessed 26 April 2013.

Lusardi, Wayne

2011 Rock, Paper Shipwreck: The Maritime Cultural Landscape of Thunder Bay, in Ben Ford (ed.) The Archaeology of Maritime Landscapes. p. 81-97, Springer Press, New York, NY.

Milne, Gustav, Colin McKewan, and Damian Goodburn

1998 Nautical Archaeology on the Foreshore: Hulk Recording on the Medway. Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England, Swindon, England.

Morris, Travis

2006 Duck Hunting on Currituck Sound: Tales from a Native Gunner. The History Press, Charleston, SC.

2010 Untold Stories of Old Currituck Duck Clubs. The History Press, Charleston, SC.

2011 Currituck as it Used to Be. The History Press, Charleston, SC.

Steward, Julian

1955 Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, IL

United States Congress

1918 An Act to give effect to the convention between the United States and Great Britain for the protection of migratory birds concluded at Washington, August sixteenth, nineteen hundred and sixteen, and for other purposes (Public Law 186. U.S. Code). Washington, D.C.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

1918 “Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918”.<http://www.fws.gov/laws/lawsdigest/migtrea.html> Accessed 26 April 2013.

Walsh, Harry M.

2008 The Outlaw Gunner. Tidewater Publishers. Centreville, MD.

Westerdahl, Christer.

2011 The Maritime Cultural Environment, in Alexis Catsambis, Ben Ford, and Donny Hamilton, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Maritime Archaeology. p. 733-762, University Press, Oxford.

Whalehead Club

2013 “The Knights’.” http://www.whaleheadclub.org/explore/the-knights/> Accessed 26 April 2013.

Preliminary Bibliography

Bates, Jo Anna Heath, Editor

1985 The Heritage of Currituck County, North Carolina, 1670-1985. The Albemarle Genealogical Society, Inc., Currituck, NC.

Bolen, Eric G.

2000 Waterfowl Management: Yesterday and Tomorrow. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 64(2):323-35.

Camp, Raymond R.

1952 Duck boats, blinds, decoys, and eastern seaboard wildfowling (Borzel book for sportsmen). Knopf Inc., New York, NY.

Carver, Heather

2010 The Duck Bible. Lulu Press, Inc., Raleigh, NC.

Conoley, William Neal

1982 Waterfowl heritage: North Carolina decoys and gunning lore. Webfoot, Wendell, NC.

Denmead, Talbot

1928 Duck Blinds and Decoys: Concerning Several Styles of Wildfowl Shooting. Forest and Stream; A Journal of Outdoor Life, Travel, Nature Study, Shooting, Fishing Yachting, p. 690.

Dudley, Jack

2001 Wings: North Carolina waterfowling traditions. Coastal Heritage Series, Morehead, NC.

Hepp, Gary Richard

1982 Behavior ecology of waterfowl (Anatini) wintering in coastal North Carolina. North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC.

Jennings, A. Burgess

2012 Images of America: Currituck County. Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, SC.

Johnson, Archie and Coppedge, Bud

1991 Gun Clubs and Decoys of Back Bay & Currituck Sound. CurBac Press, Virginia Beach, VA.

Kaminski, Richard M.

2002 Status of Waterfowl Science and Management Programs in the United States and Canadian Universities. Wildlife Society Bulletin. 30(2):616-22.

Meverden, Keith

2005 Currituck Sound Regional Remote Sensing Survey, Currituck County, North Carolina. Unpublished MA thesis, Program in Maritime Studies, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

Morris, Travis

2007 Currituck Memories and Adventures: More Tales from a Native Gunner. The History Press, Charleston, SC.

Richards, Nathan

2002 Deep Structures: An Examination of Deliberate Watercraft Abandonment in Australia. (PhD dissertation). Flinders University of South Australia, Adelaide, South Australia.

Seeb, Sami Kay.

2007 Cape Fear’s Forgotten Fleet: The Eagles Island Ships’ Graveyard, Wilmington, North Carolina. (Master’s thesis), Department of History, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

Saunders, Sr., Roy Mervin

1993 Information of the Outer Banks of Dare and Currituck County from 1776 to 1993. Pierce Printing Company, Inc., Ahoskie, NC.

Williams, Byron K., Koneff, Mark D., and David A. Smith

1999 Evaluation of Waterfowl Conservation under the North American Waterfowl Management Plan. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 63(2):417-40.