Illuminating the Lighthouse: An Historical and Archaeological Examination of the Causes and Consequences of Economic and Social Change at the Currituck Beach Light Station

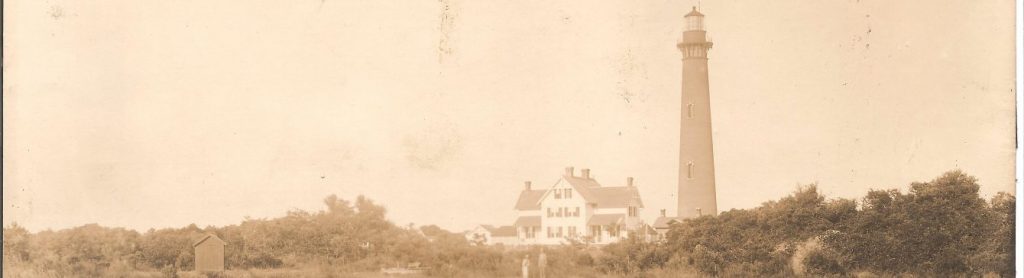

![[photo]](http://www.currituckbeachlight.com/photos/hist1.jpg)

PROSPECTUS

Scott Rose

MA Candidate

Program in Maritime Studies, Department of History, East Carolina University

11 May 2015

Abstract

The purpose of this project is gather historical and archaeological data in order to illuminate potential relationships between economic and social investment in lighthouse complexes, and enhance our understanding of the multitude of factors that drive the establishment and development of lighthouse communities. In order to do this the community surrounding the Currituck Beach Light Station in Corolla, North Carolina will serve as a case study. Historical and archaeological information will be gathered from several sources and will be assessed for correlation.

Introduction

Most research pertaining to lighthouses can be divided into four main categories. The first category of studies focuses on the architecture and technology of a lighthouse and other supporting structures on site. The focus ranges from the moving of Cape Hatteras (North Carolina) lighthouse (Snead 2010), to reconstructing lighthouse privies (Cummings 2007). Second, there are studies focused on the conservation, maintenance, and management of a lighthouse. These studies include maintenance guidelines (Schweikert 1995), environmental impacts (Amos 2002) and preservation status assessments (Hubbell 1988; Holthof 2008). The third group of studies focuses on the day to day life of the residents of the light station. Light stations were often isolated and created their own unique living environments. The children of keepers were many times unable to attend school outside of the home. These extreme living conditions have generated human interest topics. For example, the lighthouse lifestyle of female light keepers was researched and documented in a M.A. thesis (Thomas 2010). Last, there are studies focused on specific roles of lighthouses. This topic covers a variety of research interests, from the role of a lighthouse as a tourist destination and their interpretation to the public (Thomas 2008) to how lighthouses connected industries on the Great Lakes (Gillis 2011).

However, a “Light Station” is no mere beacon – it is a complex of changing buildings on a footprint that has altered considerably over time due to fluctuations in its management and the world that surrounds it. Once people began populating the area around a lighthouse, the dynamics of culture around the light station inevitably changed. What were those changes? Does economic growth correlate with other increases (such as shipping activity, or shipwrecking events)? This prospectus proposes a study which will look to expand how we perceive of the evolving roles of lighthouses within the landscape and community that surrounds it. It proposes to use the Currituck Beach Light station (located in Corolla, North Carolina) as a case study in order to ask whether there is evidence in the archaeological and historic record that demonstrates how local, state, and federal economic investment in tandem with social developments impacted and guided the development and changing role of the light station within its community.

In order to answer this overarching question, the study will look at a series of secondary research questions which consider some of the economic and social conditions that affect, and are affected by adjacent light station communities:

- What are the economic factors that guided the development of the Currituck Beach Light Station?

o What role did federal investment play in this process? What trends influenced this investment?

o What role did state investment play in this process? What trends influenced this investment?

o What role did local investment play in this process? What trends influenced this investment? - What are the social factors that guided the development of the Currituck Beach Light Station?

o What are the changes in population trends over time in this specific coastal community? Is there a correlation between population trends and any other factors?

o What risk management strategies were implemented, and when?Who implemented these risk management strategies and why?

o How did technological change affect the community? - What historical and archaeological data indicates a need for a lighthouse structure at the location of the Currituck Beach Light Station during the last half of the 19th century?

Historical Background

The United States Civil War decimated the south. Lighthouses along the Atlantic coast did not escape the destructive nature of war. Many were destroyed or their lenses demolished or removed for maritime tactical advantage. As reconstruction began, several lenses were recovered or rebuilt and many lights came back on. There were, however, a few dark spots along the coast. One of these dark spots was a sparsely inhabited strip of presumably dangerous coast along the North Carolina’s northern Outer Banks. Several structures were contracted along the coast to light the way. One of these was the Currituck Beach Light Station, which was established in 1873 at Corolla, North Carolina and began operating on 1 December, 1875 (Edwards 1999:9).

In 1873 the State of North Carolina purchased the site for the Currituck Beach Light Station and ceded the jurisdiction of it over the federal government. That same year construction began on the 162 foot structure located between the Cape Henry Light Station in Virginia and the Bodie Island Light Station in North Carolina. At Currituck, temporary living quarters for the workers, a carpenter’s shop, blacksmith’s shop and cement shed were all erected at the site. All of the construction materials were transported by barges that docked at the wharf. A rail system ran from the end of the wharf to the base of the lighthouse. Construction on the lighthouse began with piles that were driven 22 to 24 feet into the ground. Similar to the Bodie Island Lighthouse, a wooden grillage system was placed on top of the pilings. The piles had to be driven in by a steam pile driver (U.S. Lighthouse Board 1874). A multi-component foundation was placed between the grillage system and the brick conical tower.

The lighthouse boasts iron and granite window decorations and a copper sheeting roof. The Currituck Beach Lighthouse has a first order Fresnel lens. The lens was made by Sautter, Lemonier et Cie., a French optics manufacturer. Construction of the lighthouse was completed in 1875. The lighthouse tower contains over one million bricks. There are six exterior and 214 interior steps to reach the top. The exterior is still its original red brick color. This day mark distinguishes it from the other tall coastal lighthouses along North Carolina’s coast (Shelton-Roberts 2011: 121). The other three, Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, Cape Lookout Lighthouse and Bodie Island Lighthouse all have white and black painted exteriors. In 1876, the two and a half story Keepers’ house was completed (Figure 1). These were the main structures until 1920 when a second, smaller keeper’s house was added to the complex. The supporting structures for both of the keeper’s houses included cisterns, privies and storehouses (United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service [NPS] 1999:7.3-5).

After its construction, the lighthouse had its first keeper. Although small in number, the keeper and his family increased the population percentage substantially. There was very little service of any kind for most lighthouse workers. Most supplies and mail were brought to the complex periodically. What many today be perceive as isolation was an accepted lifestyle among keepers of the time. In fact, many such locations became a hub of activity in an otherwise

sparsely populated areas. The few inhabitants around Whalehead, as it was known by locals, were subsistence farmers who raised livestock and exploited feral pigs. The area was originally called Coratank, which is a term used by local Native Americans when referring to wild geese. A few people came to work and live at the light station, but the activity of construction and supply of the structure created a farther reaching impact on the area (National Park Service [NPS] 1999:8.4).

A contemporary development occurred in 1874. The lifesaving station was established nearby in Jones Hill. With the lighthouse and lifesaving station being in close proximity, this arrangement provided for an environment conducive to cultural and economic growth. The lifesaving station site may have been chosen for its proximity to the lighthouse site. The lighthouse and the lifesaving station was under construction at the same time (Marano 2012:20).

With increased traffic to the area, Whalehead’s reputation as a hunting haven soon spread. The Whalehead Club was built adjacent to the light station in 1925. It was established by a businessman from New Jersey as a hunting club and second home (Davis 2004:48). The 21,000 square foot home was later sold in 1939. The house’s Art Nouveau style architecture was a stark contrast to the simple life evident on the island (NPS 1999:7.2) (Figure 2).

An improvement in technology in 1939 could have resulted in the deterioration of most of the complex. When the Currituck Beach Lighthouse’s signal was automated by an electric generator, the light keepers were no longer necessary and were let go. With the exception of a brief period of construction and use by the Coast Guard during World War II, the site was abandoned until 1980. Eventually, efforts were made to conserve and maintain what was left on site (NPS 1999:8.8).

In 1952 the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission took over the surrounding property at Currituck Beach Light Station, but the lighthouse tower remained in U.S. Coast Guard control. The property was used by the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission for muskrat research (Shelton-Roberts 2011:112).

In 1980, Outer Banks Conservationists was formed. John Wilson IV, great-grandson of the last keeper at the Currituck Beach Lighthouse, was one of the founding members of Outer Banks Conservationists. Wilson, an architect visited the lighthouse complex and was shocked at the state of disrepair of the structures other than the tower. The group signed a lease with the

state of North Carolina for the property and-began restoration of the structures remaining on the property. By 1990 the lighthouse tower was reopened to the public for climbing. Outer Banks

Conservationists currently owns the tower and maintain controls of the property. The tower and grounds are open to the public (Shelton-Roberts 2011:112).

The study will also look at the means of transportation in the area. Profound changes occurred in waterway and road usage in the area..This change in transportation reflects technological improvements that have a direct impact on the area throughout its history.

The lighthouse structure one sees today, in its original unpainted form is now well preserved. Many original structures are still in place. It also retains its first order Fresnel lens intact. This makes it a very good example of a state of the art lighthouse in 1873. It has been listed in National Historic Register for this reason (NPS 1999). There have been some loss of structure and several changes in placement of structures on the land. The changing footprint of

buildings, the evolving property lines, and the myriad economic and social changes occurring around the station make it a very good candidate for considering how the causes and consequences of social and economic change in northeastern North Carolina may be discerned in the historical and archaeological record at the light station, and interpreted.

Theory

This research will utilize a behavioral archaeological approach to understand the cultural site formation processes in the Currituck Beach Light Station community. Schiffer says, “Behavioral approaches bring to landscape studies an explicit framework for (1) investigating formation processes at the landscape level, and (2) understanding how people interact with places, spaces and landscapes over time in their explorations, alterations, use and maintenance of these elements” (Schiffer 2010:186). Formation processes include both non-cultural transformation processes and cultural transformation processes. This study’s primary focus will be on the cultural transformation processes that shaped the lighthouse complex and surrounding

community. Cultural formation processes include five subcategories: reuse, cultural deposition through loss, cultural deposition through abandonment, reclamation, and disturbance (Schiffer 2010:31-41). Each of these processes potentially occurred at the light station. The behavioral approach framework is well-suited for understanding the lighthouse complex and its everchanging relationship to the community surrounding it. Schiffer also provides three specific dimensions that should be considered when attempting to understand what attracted people to the

site and the sequence of activities that occurred there. These three dimensions are: formal, relational, and historical. Research of the formal dimensions includes analyzing the formal land attributes to understand why people used or avoided particular sections of the landscape. Formal land attributes include size, color, location, and history of use. The relational dimension examination consists of finding how the movement of people connects land elements. Finally, the historical dimension uses the life history model to explore the formation, maintenance and transformation of the landscape (Schiffer 2010:192). By utilizing these basic approaches to cultural formation processes and the human decision making involved, a new understanding of the Currituck Beach Light Station through time will be reached.

Research Methodology

The research methodology for this project consists of three phases: historical research, archaeological research, and analysis. Each phase consists of multiple sub-phases of research. When combined, this methodology will serve to support and expand the current knowledge of the Currituck Beach Light Station.

Historical Research

Consultation of secondary sources will include currently available and attainable sources that document the development and evolution of seamark technology, life experiences of lighthouse keepers, and other studies. These other studies have been effective in attaining similar goals with other central topics. Examples of these topics are: cultural impacts of lifesaving stations, sea ports, fishing communities, and the evolution of other maritime based communities. Some of these secondary sources are held by the author. Others are obtainable through purchase or through loan or download from the library system at East Carolina University.

There are many resources regarding lighthouses that are intended for the general public audience. The most prominent writers on North, Carolina lighthouses are David Stick (1952) and Cheryl Shelton Roberts and Bruce Roberts (2004, 2011). Most of these lighthouse guides provide brief information about the Currituck Beach Light Station and when they do provide information it is centered on the lighthouse and is lacking in culturally relevant data.

All the previous documentation concerning this light station is lacking in information about cultural and social change. There have been numerous studies done on coastal communities; however, none have been completed that have a light station as their primary focus. One example of a similar study is Amy C. Leuchtmann’s Master’s thesis “The Central Places of Albemarle Sound: Examining Transitional Maritime Economies through Archaeological Site Distribution” (2011). Ms. Leuchtman’s study focused on several different centralized locations and may provide a broad sweep of economic trends in the region within which the lighthouse is a part.

A thorough search of historical documents and photographic evidence will be conducted. This search will include the National Archives in downtown Washington DC. This facility holds records from the US Lighthouse Board which will prove to be useful. The records labeled as 26.6.4 are of primary concern. These records pertain to the 5th Coast Guard District, Portsmouth, VA (DC, MD, NC, and VA). The Currituck County Historical Society archives data concerning the local history of the area. Historic records at the Outer Banks History Center in Manteo will be consulted regarding local history. There is a collection in their archive entitled “Shipwrecks, Lighthouses and Aids to Navigation.” US Census Bureau data will also be consulted for population statistics for the area. Lighthouse historic societies in the area will also be consulted, as well as ongoing investigations at the Currituck Light Station itself. Particular attention will be paid to photographic documentation of the lighthouse complex and surrounding properties.

The historical research will have two main components. First, research will be performed on the history of the construction of the light station. The first objective will be to compile a historical description of the station. This will include changes is ownership and structural additions and removals on the property. The purpose of the light station at the various stages of its existence will be investigated. The second objective will be to examine the economic and community factors involved in building and maintaining the light station. The last objective of this component will be to examine the site’s evolution in relation to the economic climate and demographic changes along the coast. Evidence of time, effort and monetary investments by federal, state and local entities will be compiled from the listed sources and will be evaluated in context according to interest and motives.

The second component of the historical research will be an investigation of the reciprocal influence of the light station on the community through time. This will entail examining important events occurring around the light station. The frequency of shipwrecks before and after construction and major funding events would be an example of the type of research that would be conducted. An additional historical research element that falls between these categories is the reported wreck of Brooklyn. Local lore suggests this ship was supposedly delivering bricks to the lighthouse complex for construction of the tower (though no historical records have thus far been found). Due to its connection with the light station, a thorough historic investigation into the Brooklyn is warranted. If this research proves advantageous, underwater archaeological survey may be necessary to try and locate the wreck.

Archaeological Methodology

The archaeological research component of this study can be divided into five phases. The goal of the stages is to culminate in a complete description of the light station will be developed, that can later be depicted in a virtual model.

Survey of the Currituck Light Station complex

Building upon a survey already conducted by the UNC-Coastal Studies Institute and East Carolina University’s Program in Maritime Studies during their 2013 fall field school, this phase will be comprised of non-disturbance techniques including a ground survey and total station mapping of structures and other exposed features such as remaining wharf structures, concrete slabs and fencing. Some of these structures are underwater and cannot be mapped except through the use of a Total Station. Total station mapping allows for precise location of points three-dimensionally that will be mapped into a three dimensional modeling program as well as statistical analysis. These points will be added to the map in order to aid in understanding the layout of the original site and changes to the site throughout time. This study will utilize reflector-dependent total station and data-logger for accurate three-dimensional mapping of cultural features and topography.

Terrestrial Remote Sensing

Remote sensing techniques may be used to possibly locate and identify buried objects, structures and features located in the lighthouse complex. The property will be systematically divided into quadrants and then surveyed. Several techniques may be utilized for surveying. This work will be completed in the context of the present-day property boundaries of the lighthouse complex. If work needs to be done on adjoining properties, attempts will be made to acquire permission from owners and any permits required. These details will be determined before archaeological work begins. Fellow East Carolina University students will aid in these endeavors on a volunteer basis. All of the equipment needed to fulfill this research will be provided by East Carolina University, or by the UNC Coastal Studies Institute. Most of the research will occur during July of 2015 and when time and resources permit throughout the remainder of 2015 and 2016.

First, a magnetometer (Geometrics Magmapper G-858 Gradiometer) survey will be completed. Magnetometry and gradiometry are passive techniques that reveal ferrous anomalies in the subsurface. Passive techniques measure magnetic fields as they exist without any active injection of energy into the ground. Anomalies could indicate areas of activity such as animal pinning, trash disposal areas, and metal working areas. All of these areas would be of great interest for future researchers. If these anomalies can be matched with historic information, it may be possible to locate sites of previous buildings, and add to our understanding of the sequential occupation of the site and its occupants. Gradiometers are most useful for locating large anomalies like foundations (Johnson 2006:110). Some of this data has already been gathered during the aforementioned 2013 field school, and is held by the UNC-Coastal Studies Institute’s Maritime Heritage Program.

The second technique that may be used is metal detection. This active technique involves using metal detectors to reveal metal signatures that the gradiometer is not able to recognize, Small anomalies, such as nail clusters, are more likely to be located with a metal detector (Green 2004:159-161).

Another possible phase of research is the use of laser scanning technology to acquire data point clouds of existing structures on the property for use in modeling software. As the need arises and schedules dictate, a laser scanning device may be sought. This phase may not be actualized if the photogrammetry phase (below) is successful.

Photogrammetry

One other technique used will be photogrammetry. This will be undertaken in order to capture accurate three dimensional models of the present-day standing structures at the light station. Software called Photoscan (Agisoft) will be utilized. This program allows numerous photos to be stitched together to form a three dimensional model (see Figure 3). This model will then be combined with information gathered from the total station survey and possibly information gathered from laser scan of the subject. The primary investigator will also provide the photographic equipment required for data collection in this phase.

Underwater Survey

The Currituck Beach Light Station extends beyond the terrestrial environment into the adjacent waterways. To fully understand the construction and development of the station a survey of these areas is needed. The original construction included a wharf, a railway on the property and a platform on Church’s Island. Deep draft cargo ships unloaded materials at the platform. Materials were then transported across the sound to the wharf and railway. The relocation and recording of the wharf, railway, platform and any lost delivery vessels is possible with in-water survey. Surveying these features will enhance our understanding of the station’s previous extent and impact on the landscape.

Additionally, local residents report the loss of a shipwreck named Brooklyn within close proximity to the light station which was delivering building materials for the construction of the lighthouse at the time of its loss. A survey of the presumed area should prove useful in determining if the wreck is present at the location. The discovery and inspection of the shipwreck may provide clues to the placement of lighthouse, and will further enhance our understanding of the extent of the lighthouse’s influence on the landscape.

The data gathered through each of these techniques will have its own inherent data uncertainties. These uncertainties will be described in detail, and quantified if possible. This data will be stored and archived at two locations. The first location is at Eller House Library. The second location will be at the Currituck Beach Light Station where the visualizations can hopefully be used in an educational context.

Analysis

The analysis phase of this project will be composed of three activities – quantitative analysis of historical records, digital modeling of archaeological data and the merging of aggregated historical data into the virtual modeling for geospatial analysis.

After the historical and archaeological data has been gathered, statistical analysis must be conducted in order to locate correlations between economic change and archaeological evidence or between the construction of the Currituck Beach Light Station and an increase or decrease in shipwreck events.

The economic and social investments made by local regional and federal entities in the events affecting the lighthouse complex throughout its history will be evaluated through qualitative analysis of gathered historic documentation describing time and effort expended on the topic. Where possible, a more quantitative approach will be used to illuminate any correlative patterns in economic and social data. This will be accomplished through the use of statistical software such as SPSS. Any correlations will be graphed and displayed. These illustrations will provide justification for assumptions and conclusions made based on the datasets. Fiscal data will be acquired from several sources including the United States Census Bureau, The United States Lighthouse Board, the Underwater Archaeology Branch of the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, and the United States Coast Guard. This methodology follows precedents set by previous students in the Maritime Studies Program (Leuchtmann 2011) (Marano 2012) and (Price 2006).

While the methods outlined in the archaeological methodology can capture the presentday standing structures at the light station, and may provide visual datasets for examination, some past features may need to be reconstructed virtually. For example, once blueprints or construction plans for the lighthouse complex can be located, they may be used in concert with other information to establish a three dimensional model of the Currituck Beach Light Station complex as it was originally built. Measurements for previous structures will be based on data gathered from historic photographs, archaeological remains, historic accounts, and original construction plans. Such a model will be created using McNeel Rhinoceros software. After it is created, the model will then be geo-rectified in ESRI ArcGIS to situate it into the appropriate spot on the landscape map. Several layers will be included in order to illustrate changes over time. Each of the documented changes to the complex, as well as each of the changes indicated by archaeological evidence will be assigned a separate layer. One layer will indicate the original survey of the land used for construction. The next will indicate the first stage of construction. Subsequent layers will indicate continued construction and changes to the property as each relates to a date or date range. The final layer will represent the site as it exists today. The data uncertainty of current and previous research will be noted and explained whenever necessary. Each instrument used to gather information will be tested to discover its accuracy. Error will be determined for each user and each variation in use of the instrument. This information will then be made available for future reference.

The final stage of the methodology will be the creation of a geodatabase and a diachronic spatial visualization. In order to do this, two programs by ESRI (ArcMap and ArcScene) will be used. All of the data from the first four phases will be input into ArcMap. The total station data will be logged along with GPS coordinates that can be input into a GIS to correlate with current and historical maps. These historic maps will have to be geo-rectified in ArcMap after finding reference points on the ground. Some of these points have already been located, and recorded with GPS (Translating to UTM WGS84). Second, 3D model of the light station buildings created using photogrammetric techniques will be merged onto the two-dimensional “footprints” created via the total station survey data and geo-rectified maps of the area. This methodology will allow digitized architectural features as well as possible archaeological discoveries such as evidence of fencing, animal corrals, midden piles or other ephemeral objects to be layered separately and viewed separately or together on a map. Known features that will possibly be located and identified include the original granite boundary markers, granite fencing, shipwreck sites and wharf pilings. The layered method will allow for a three dimensional model that will illustrate the changes through time at the site. The timeframe of these changes through history will be determined through historic research. Much of the documents have already been gathered by Megan Agresto, the Managing Director of the Currituck Beach Light Station. Other features discovered on site will be dated according to historic photographic evidence, or relative dating according to material culture and diagnostic artifacts. If these methods fail, a decision will be made to either include the new features in the report only, or to make assumptions about the dates of each feature and include them in the illustrations. This will probably be done in a separate layer, and the uncertainty will me noted. This final product will resemble a recreation of the light station in a three dimensional virtual environment. It will allow for greater insight into its evolution within the surrounding landscape through time. This will be primarily a qualitative explanation of the changes to the site over time. There will be quantitative data and explanations of historic occurrences and its effects on population, economy, and various industries included in the presentation. Information from the historical record, as well as aggregated economic and social data may also be associated with elements of the light station model. The process of model creation will allow researchers to look at the site from many different viewpoints and perspectives that may be impossible otherwise. It will also allow a comparison of planned construction, actual construction, and deterioration and change through time based on economic and cultural change in the area. Finally, although it is not the focus of the study, it could allow for a rudimentary comparisons of the accuracy of large scale models produced through photogrammetry, to those produced through computer aided drafting software and possibly through laser scanning methods.

The combination of the historical and archaeological research will allow for a reassessment of the construction and development of the Currituck Beach Light Station. The thorough archaeological research of the station will potentially supplement, support or refute the historical record and provide a new research paradigm for lighthouse archaeology. The three dimensional model anticipated should prove useful for historians and public archaeologists in their attempt to convey the narrative of this historic location, as well as shed light on the development of other similar coastal communities.

References

Amos, Jenifer Lee

2002 Nondestructive Stress Wave Evaluations of the historic Port Isabell Lighthouse Masonry Tower Wall during Restoration Process. PhD Dissertation. University of Texas at Austin.

Cummings, Margaret A.

2007 Cape May Point Lighthouse: the reconstruction of privies for study as cultural artifacts. Master’s Thesis. California State University, Dominguez Hills.

Davis, Susan Joy

2004 The Whalehead Club: Reflections of Currituck Heritage. The Donning Company Publishers. Virginia Beach.

Gillis, Lisa M.

2011 Lighthouses as an overlapping boundary between maritime and terrestrial landscapes: How lighthouses served to connect the growing industries of the Keweenaw Peninsula with the world market. PhD Dissertation. Michigan Technological University. University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI.

Green, Jeremy

2004 Maritime Archaeology, a Technical Handbook. 2nd Ed. Elsevier Academia Press, San Diego, CA.

Holthof, Benjamin Lee

2008 Lighthouse Archaeology: the Port MacDonnell and Cape Banks Lights. Master’s Thesis. Flinders University of South Australia.

Hubbell, Robin

1988 Historic Georgia Lighthouses: a study of their history and an examination of their present physical state for historic preservation purposes. Master’s Thesis. University of Georgia.

Leuchtmann, Amy C.

2011 The Central Places of Albemarle Sound: Examining Transitional Maritime Economies Through Archaeological Site Distribution. Master’s Thesis. East Carolina University

Marano, Joshua

2012 Ship Ashore! The Role of Risk in the Development of the United States Life-Saving Service. Master’s Thesis, Department of History, East Carolina University, Greenville.

Price, Franklin

2006 Conflict and Commerce: Maritime Site Distribution as Cultural Change on the Roanoke River, North Carolina. Master’s Thesis, Department of History, East Carolina University,

Greenville.

Schiffer, Michael Brian.

2010 Behavioral Archaeology: Principles and Practice. Equinox Publishing Ltd. London.

Schweikert, Carol Ann Johnson.

1995 The Development of Exterior Maintenance Guidelines for Lighthouses in Six Geographic Regions. Master’s Thesis. Ball State University, IN.

Shelton-Roberts, Cheryl, and Bruce Roberts.

2004 North Carolina Lighthouses: A Tribute of History and Hope. Our State Books. Greensboro, NC.

2011 North Carolina Lighthouses: Stories of History and Hope. Globe Pequot Press. Guilford, CT.

Snead, Nathan.

2010 Moving a Lighthouse: Cape Hatteras. Master’s Thesis. East Carolina University,Greenville, NC.

Stick, David.

1952 Graveyard of the Atlantic: Shipwrecks of the North Carolina Coast. The University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill, NC.

Thomas, Virginia Neal.

1997 Woman’s Work: Female Lighthouse Keepers in the Early Republic, 1820 – 1859. Master’s Thesis. University of North Carolina Greensboro.

United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service. [USDI]

1999 section 7, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Currituck Beach Lighthouse Complex. US Government Printing Office.

Tentative Bibliography:

Adamson, Hans Christian

1955 Keepers of the Lights: a Saga of Our Lightships and the Men Who Guide Those Who Sail the Seas. Greenberg Press, NY.

Amos, Jennifer Lee.

2002 Nondestructive stress wave evaluations of the historic Port Isabel lighthouse masonry tower wall during restoration processes. PhD Dissertation. University of Texas at Austin.

Angley, Wilson.

1997 North Carolina shipwreck references from newspapers of the late eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Microfilm 629, Series 3, Number 14, North Carolina Division of Archives and History Research Branch, Historical Research Reports, Raleigh,

NC.

Clifford, Mary Louise, J. Candace Clifford

1993 Women Who Kept the Lights: An Illustrated History of Female Lighthouse Keepers. Cypress Communications. Williamsburg, VA.

Cummings, Margaret A.

2007 Cape May Point Lighthouse: the reconstruction of privies for study as cultural artifacts. Master’s Thesis. Calfiornia State University, Dominguez Hills.

Edwards, Jenny

1999 To Iluminate the Dark Space: Oral Histories of the Currituck Beach Lighthouse. Outer Banks Conservationists, Inc. Corolla, NC.

Friedman, Adam

2008 The Legal Choice in a Cultural Landscape: An Explanatory Model Created from the Maritime and Terrestrial Archaeological Record of the Roanoke River, North Carolina. Master’s Thesis, Department of History, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

Gillis, Lisa M.

2011 Lighthouses as an overlapping boundary between maritime and terrestrial landscapes: How lighthouses served to connect the growing industries of the Keweenaw Peninsula with the world market. PhD Dissertation. Michigan Technological University. University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI.

Green, Jeremy

2004 Maritime Archaeology, a Technical Handbook. 2nd Ed. Elsevier Academia Press, San Diego, CA.

Hatch, Heather E.

2013 Harbour Island: The Comparative Archaeology of a Maritime Community. Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University.

Holland, F. Ross.

1989 Great American Lighthouses. The Preservation Press, Washington, D.C.

Holthof, Benjamin Lee.

2008 Lighthouse Archaeology: the Port MacDonnell and Cape Banks Lights. Master’s Thesis. Flinders University of South Australia.

Hubbell, Robin.

1988 Historic Georgia lighthouses: A study of their history and an examination of their present physical state for historic preservation purposes. Master’s Thesis. University of Georgia.

Johnson, Jay K.

2006 Remote Sensing in Archaeology: An explicitly North American perspective. The University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa.

Johnson, Matthew

2010 Archaeological Theory, an Introduction. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell. Oxford.

Kemp, Peter, editor

1976 The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea. Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Kozma, LuAnne Gaykowski, editor

1987 Living at a Lighthouse: Oral Histories from the Great Lakes. Great Lakes Lighthouse Keepers Association. Detroit, MI.

Leuchtmann, Amy

2011 The Central Places of Albemarle Sound: Examining Transitional Maritime Economies through Archaeological Site Distribution. Master’s Thesis, Department of History, East

Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

Levitt, Theresa

2013 A Short, Bright Flash: Augustin Fresnel and the Birth of the Modern Lighthouse. W. W. Norton & Company, New York, NY.

MacKenzie, Morgan

2011 American Lightships, 1820-1983: History, Construction, and Archaeology within the Maritime Cultural Landscape. Master’s Thesis, Department of History, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

McCabe, Christopher

2007 The Development and Decline of Tar-Pamlico River Maritime Commerce and its Impact upon Regional Settlement Patterns. Master’s Thesis, Department of History, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

McErlean, Thomas, Rosemary McConkey, and Wes Forsythe

2002 Strangford Lough: an archaeological survey of the maritime cultural landscape. Northern Ireland Archaeological Monographs NO 6. The Blackstaff Press, Belfast, Ireland.

Marano, Joshua

2012 Ship Ashore! The Role of Risk in the Development of the United States Life-Saving Service. Master’s Thesis, Department of History, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

Naish, John

1985 Seamarks: Their History and Development. Stanford Maritime, London.

Putnam, George R.

1937 Sentinel of the Coasts: The Log of a Lighthouse Engineer. W.W. Norton & Company Inc., New York, NY.

Schiffer, Michael Brian.

2010 Behavioral Archaeology: Principles and Practice. Equinox Publishing Ltd. London.

Schweikert, Carol Ann Johnson.

1995 The Development of Exterior Maintenance Guidelines for Lighthouses in Six Geographic Regions. Master’s Thesis. Ball State University, IN.

Shelton-Roberts, Cheryl, and Bruce Roberts.

2004 North Carolina Lighthouses: A Tribute of History and Hope. Our State Books. Greensboro, NC.

2011 North Carolina Lighthouses: Stories of History and Hope. Globe Pequot Press. Guilford, CT.

Snead, Nathan.

2010 Moving a Lighthouse: Cape Hatteras. Master’s Thesis. East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

Stick, David.

1952 Graveyard of the Atlantic: Shipwrecks of the North Carolina Coast. The University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill, NC.

Thomas, Virginia Neal.

1997 Woman’s Work: Female Lighthouse Keepers in the Early Republic, 1820 – 1859. Master’s Thesis. University of North Carolina Greensboro.

United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service.

1999 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Currituck Beach Lighthouse Complex. US Government Printing Office.

U.S. Light House Board

1874 Annual Report of the Light House Board to the Secretary of the Treasury. Government Printing Office. Washington, DC.

Weir, Andrew

2007 A Historical and Archaeological Analysis of the Middle Island Life-Saving Station: Applying Site Formation Theory to Coastal Maritime Infrastructure Sites. Master’s Thesis, Department of History, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

Westerdahl, Christer.

1992 The Maritime Cultural Landscape. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 21(1): 5-14.

Archives to be consulted:

National Archives, Washington, D.C

Currituck County Records Office

Currituck County Historical Society

North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, Underwater Archaeology Branch

North Carolina Maritime Museum