“But the first film had to show the crime – and the lie. The crime: that was indeed my father who was murdered there. The lie: my mother was one of the ladies who was constantly trying to find information, she was writing to the Red Cross in London and Switzerland, she clung on to the hope that her husband would return from the war. She was lied to that he didn’t die in Katyń, and only gradually did we discover the truth. We learnt that there were other camps, and those camps were also liquidated. In short, we learnt about the machinery of death.”

Andrzej Wajda, quoted in The Krakow Post, June 19, 2009.

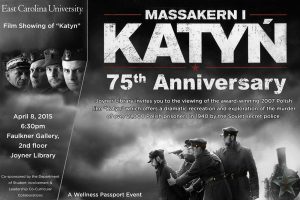

Tonight, Joyner Library is pleased to present, in commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the Katyn Forest Massacre, the award-winning 2007 Polish film Katyn. The film is directed by Andrzej Wajda, a highly-acclaimed filmmaker who has directed nearly 40 films in a career spanning over five decades. Wajda’s contributions as a director would be recognized in 2000 with an Academy Award for Lifetime Achievement, an honor for which he was nominated by Steven Spielberg. Katyn would be the fourth of Wajda’s films to be nominated for the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film.

1. The Context

Katyn is a deeply personal film for Wajda, one that he spent decades hoping he could make, yet doubting that he would ever be permitted the opportunity. Among the 21,857 Poles murdered at the behest of Josef Stalin in April-May 1940 was Wajda’s father Jakub, a Captain in the Polish army. Only 14 years old at the time, Wajda watched how his mother was consumed by years of grief and uncertainty. Communist authorities in Poland suppressed almost all discussion of the Katyn atrocities, especially if they hinted at Soviet guilt. Finally, the fall of the Soviet empire in eastern Europe in 1989 made it possible to openly discuss the Katyn massacre without fear of official repercussions. In addition, Soviet admission of guilt for Katyn in 1990, followed by the unraveling of the USSR, revealed many previously unknown facts about the killing operation of April-May 1940.

Seventy five years later, the Katyn Forest Massacre remains a highly-charged symbol of historical memory that shapes the distrustful way many Poles, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, and Ukrainians view Russia. It is an integral part of the current struggle over the history of World War II in eastern Europe, in which Russia portrays itself as the heroic liberator of Poland and the Baltic states from the Nazis, while the latter see themselves as victims of Soviet oppression and occupation. Wajda’s film has become a key part of this struggle, a cinematic symbol of the numerous Soviet deportations and mass killing actions during the 1930s and 1940s conducted in the region that historian Timothy Snyder has called the “Bloodlands”. Both Ukraine and Estonia have honored Wajda for his achievement in making Katyn.

While keeping this context in mind, it is important to note that Wajda’s Katyn is not an anti-Russian film. It even includes a sympathetic Russian character in the form of a Soviet army officer who saves the wife and daughter of the main Polish protagonist from the secret police. In April 2010, the film was shown twice on Russian television in a gesture of reconciliation, and Russia even presented Wajda with the Order of Friendship in December of that year.

2. The Film

While Katyn is a deeply personal film, it is not autobiographical. The film is strongly rooted in the historical record; however, the characters themselves are fictional archetypes who represent broader themes and ideas. The specific events portrayed in the film, while in accord with historical scholarship, are there at least in part for their symbolic value. For example, the film’s opening sequence set on the bridge, where one crowd of terror-stricken Poles flees east to escape the Nazis, only to encounter another, equally terrified crowd fleeing west from the advancing Soviets.

Most of the film is spent not on the massacre itself, but rather on the impact of the atrocity and subsequent Soviet cover-up on the families and friends of those murdered. After the Soviets drive the Nazis from Poland in 1945, the characters in the film are confronted with a terrible dilemma: either to be part of the building of a “new” Poland, albeit on Soviet terms and requiring them to accept the Soviet lie that their loved ones were murdered by the Germans; or, to insist on telling the truth about what happened at Katyn, at the risk of marginalization or worse.

Finally, after taking us through 1945, Wajda uses the device of a recovered diary to take us back to April 1940 and show in stark, unsparing fashion the fate of those taken by the Soviet secret police into the Katyn Forest. In Wajda’s view, giving the viewer a window on the killings was a necessity. As he told the Krakow Post in July 2009, “For the first film, I had to show the crime and its consequences.” (Hodge, “Katyn”)

As Alexander Etkind and his fellow authors have noted, most historical films have uplifting endings. (Etkind, 49-50) Even a film as harrowing as Schindler’s List gradually lifts the audience out of the horrors into which they have been submerged for most of the film. Wajda’s Katyn grants the audience no such luxury. It ends with the horrifying spectacle of the Katyn executions. It is left to the audience to supply its own “happy” ending: to note that the very film they are watching is a reminder that Poland would ultimately shed Soviet domination; that the truth about Katyn would eventually prevail; that Wajda was, in fact, able to make the film he needed to make, showing both the crime that claimed the life of his father, and the lie that consumed his mother.

Katyn will be shown tonight, Wednesday, April 8, at 6:30 PM in the Faulkner Gallery of Joyner Library. The screening is co-sponsored by the Department of Student Involvement & Leadership Co-Curricular Collaborations. This is a Wellness Passport event.

Sources:

Etkind, Alexander, Rory Finnin, et al. Remembering Katyn. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2012. (Joyner Stacks: D804.S65 R45 2012)

Hodge, Nick. “Andrzej Wajda on Katyń: The Full Transcript.” Krakow Post, June 23, 2009. (via Internet Archive)

Hodge, Nick. “Katyń: An Interview with Director Andrzej Wajda.” Krakow Post, June 19, 2009. (via Internet Archive)

“Katyn,” Wajda.pl, n.d.(via Internet Archive)