This spring marks the 75th anniversary of one of the gravest affronts to civil liberty in American history, the forcible internment of an estimated 117,000 Japanese-Americans living in the states of California, Oregon, Washington, and Arizona in the spring of 1942. A complex combination of fear and anger sparked by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and subsequent victories in the Pacific, paranoid countersubversive fear of a “fifth column,” and long-standing racial prejudice, all converged in the two months following Pearl Harbor to create an almost irresistible momentum in favor of the deportation of Japanese-Americans from the west coast. While the House Special Committee on Un-American Activities played no real role in bringing about internment, it did hold hearings that attempted to justify the federal government’s actions.

1. “A Jap’s a Jap”: The Decision for Internment

In December 1941, there were an estimated 120,000 persons of Japanese descent living in the Pacific coastal region of the United States. Approximately two thirds of this number were, in fact, American citizens. Despite persistent racial prejudice from much of the native white population, Japanese-American communities had grown and thrived on the west coast since the early 20th Century. Despite this population’s embrace of their new country, there were many who feared that Japanese in America would become a “fifth column” on behalf of Japan in the event of war between the two countries.

At first, in the immediate aftermath of Pearl Harbor, there was no real momentum for internment of Japanese residents on the Pacific coast. However, as Japanese forces won victory after victory against American, British Commonwealth, and Dutch forces in the Far East, fear mounted of a possible Japanese attack on the west coast. Sadly, all too many Americans directed their anger over Japanese actions at their fellow citizens of Japanese descent. Unfounded rumors spread like wildfire, alleging widespread sabotage and espionage activities by Japanese-Americans on behalf of Tokyo. Racial prejudice further fueled such fears, as nativist groups exploited this overheated environment to demand the expulsion of Japanese-Americans from the Pacific coast. Finally, many newspapers and prominent west coast politicians, such as the mayor of Los Angeles, the governor of California, and numerous congressmen, joined the growing chorus demanding action against Japanese-Americans.

Federal authorities initially resisted these calls. Attorney General Francis Biddle resolutely opposed any form of mass internment, or incarceration based solely on race or national origin. The organizations directly responsible for coping with domestic pro-Axis subversion, the FBI, military intelligence, and naval intelligence, all insisted that internment was unnecessary and the problem of possible subversion among Japanese-Americans was well in hand.

Initially, the Army likewise opposed the deportation of persons of Japanese descent from the west coast. However, as the public outcry against Japanese-Americans grew, the commander of military forces along the Pacific coast, Lt. General John L. DeWitt, allowed himself to be persuaded of the necessity of mass internment. On February 14, 1942, DeWitt recommended that all Japanese-Americans, citizens and non-citizens, be removed from “sensitive areas.” Bowing to both the recommendation of his general, and to the growing public hysteria, President Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, issued Executive Order No. 9066, which authorized the removal of all persons of Japanese descent from the western areas of California, Oregon, and Washington.

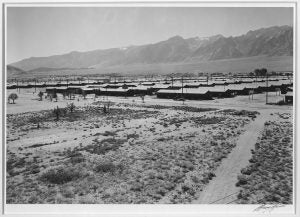

In all, some 117,000 Japanese-Americans were deported from the west coast during the spring of 1942. At first they were encouraged to leave voluntarily, and to go anywhere else in the US that they wished. Starting in March, remaining Japanese residents were ordered to report to the authorities, and taken to government-run internment centers. Allowed to bring only what they could carry, many of the internees lost almost everything. Eventually, most deportees ended up in one of 10 major internment camps, most located in remote areas of the western US. These camps were run by an organization called the War Relocation Authority (WRA), which was part of the Interior Department. Japanese-Americans living elsewhere in the continental United States were not interned, nor were those living in Hawaii, despite their closer proximity to the theater of military operations.

The crude, racialist logic behind the mass internment of Japanese-Americans was clearly illustrated in comments made by General DeWitt. Testifying before a congressional subcommittee in April 1943, he defended his decision in the following terms:

…The danger of the Japanese was, and is now, -if they are permitted to come back- espionage and sabotage. It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen, he is still a Japanese. American citizenship does not necessarily determine loyalty. (Walker, “A Slap’s a Slap”)

As DeWitt infamously told the press, “a Jap’s a Jap.” No similar logic was applied to German-Americans or Italian-Americans.

2. HUAC Investigates Japanese-Americans

While the House Special Committee on Un-American Activities, which would become better known starting in 1945 as simply the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), played a relatively minor role in Japanese-American internment, the committee did support the decision. In particular, HUAC published several volumes and reports on the activities of Japanese “patriotic societies” that allegedly fostered loyalty to Tokyo at the expense of Washington (see list of sources below.)

HUAC’s main contribution to the internment of Japanese-Americans was a series of public hearings focused on the internment facilities, in June-July, 1943 by a three-member subcommittee, consisting of Reps. John M. Costello (D-CA), Karl E. Mundt (R-SD), and Herman P. Eberharter (D-PA). On September 30, 1943, HUAC issued a report summarizing the results of this investigation. Costello and Mundt, supported by the bulk of the committee, criticized the WRA for allowing the internment camps to become, in HUAC’s view, hotbeds of pro-Tokyo subversion. Among other offenses, the committee condemned the WRA for permitting the teaching of judo and other Japanese cultural activities, which allegedly inhibited the inculcation of “positive Americanism” among the internees. Finally, the HUAC majority called for more rigorous efforts to separate loyal from disloyal internees, and demanded the implementation of a “thoroughgoing program of Americanization” in the camps. (Establishment of the War Relocation Centers, 8, 16)

Alone among HUAC’s membership, Rep. Eberharter dissented strongly from this viewpoint. In a scathing critique published along with the majority report, Eberharter wrote that “I cannot avoid the conclusion that the report of the majority is prejudiced, and that most of its statements are not proven.” (Establishment of the War Relocation Centers, 17) Rejecting the report’s depiction of life in the camps, and its single-minded focus on subversion, Eberharter strongly defended the WRA against HUAC’s charges. His comment on the Americanization proposal is especially telling, bitingly pointing out the absurdity behind it:

Certainly, we would need an extraordinarily intensive Americanization program for loyal American citizens who are detained in seeming contradiction of American principles and the “four freedoms.” (Establishment of the War Relocation Centers, 28)

Few statements so eloquently expressed how the countersubversive obsession at the heart of HUAC all too often made a mockery of the American ideals the committee claimed to defend.

3. Conclusion

Starting in 1943, Japanese-Americans gradually began to be released from the internment facilities. In December 1944, the Roosevelt Administration announced that all remaining internees would be freed. No credible evidence of widespread subversion or espionage among Japanese-Americans was ever found. In 1980, Congress created a commission to investigate the internment. Its report, released in December 1982, in many ways offers the final word on a sad chapter in American history:

The promulgation of Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity, and the decisions which followed from it….were not driven by analysis of military conditions. The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership. Widespread ignorance of Japanese Americans contributed to a policy conceived in haste and executed in an atmosphere of fear and anger at Japan. A grave injustice was done to American citizens and resident aliens of Japanese ancestry who, without individual review or any probative evidence against them, were excluded, removed and detained by the United States during World War II. (Personal Justice Denied, 18)

In 1988, the Civil Liberties Act was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Reagan. This legislation condemned the internment of Japanese-Americans, and offered a presidential apology and financial compensation to the internees.

CWIS Materials on the Internment of Japanese-Americans:

Establishment of the War Relocation Centers: Report and Minority Views of the Special Committee on Un-American Activities on Japanese War Relocation Centers. September 30, 1943. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4. Un 1/2: Un 1/RPT.717)

Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Appendix VI: Report on Japanese Activities, Hearings before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Seventy-Seventh Congress, First Session. 1942. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4: Un 1/2: Un 1/app./pt. 6-8)

Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Appendix -Part VIII: Report on the Axis Front Movement in the United States: Second Section -Japanese Activities, Hearings before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Seventy-Eighth Congress, First Session. 1943. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4: Un 1/2: Un 1/app./pt. 6-8)

Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States, Volume 15, Hearings before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Seventy-Eighty Congress, First Session. June-July, 1943. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4: Un 1/2: Un 1/v. 15)

Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States, Volume 16, Hearings before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Seventy-Eighty Congress, First Session. November-December, 1943. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4: Un 1/2: Un 1/v. 16)

War Relocation Centers. Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Military Affairs, United States Senate, Seventy-Eighth Congress, First Session. 4 v., 1943-44. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4. M 59/2: W 19/10)

Additional Federal Government Sources:

Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. ‘The War Relocation Authority & the Incarceration of Japanese-Americans During World War II.’ February 2005. (Collection of primary source documents from Truman’s papers, including items from the War Relocation Authority.)

Library of Congress. ‘Japanese – Behind the Wire.’ February 2005.

Manzanar National Historic Site, Tule Lake Unit, National Park Service. ‘A Brief History of Japanese American Relocation During World War II.’ February 2005.

National Archives and Records Administration: Educator Resources: Japanese Relocation During World War II. (Brief background, with links to primary source items from the National Archives.)

National Archives and Records Administration: Japanese American Internment. (“To commemorate the 75th Anniversary of FDR’s Executive Order 9066 that interned Japanese Americans during World War II, the National Archives makes widely available its extensive related holdings including photos, videos, and records that chronicle this chapter in American history.”

National Archives and Records Administration: Japanese Relocation and Internment. (Directory of relevant, high-quality sources.)

National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. ‘Japanese Americans in World War II.’ A National Historic Landmark Theme Study (draft), February 2005.

Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. 1983; 1992. (Joyner Docs Stacks: Y 3.W 19/10:J 98 (2 v.); and Joyner Docs Stacks: Y 4.In 8/14:P 43; Joyner Stacks D769.8.A6 P47 1983)

Unrau, Harlan D. Manzanar National Historic Site, California: The Evacuation and Relocation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry during World War II: A Historical Study of the Manzanar War Relocation Center. United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1996. (Joyner Docs Stacks: I 29.58/3:M 31/V.1) (An extensive history of the Manzanar relocation camp.)

Walker, Alan. “A Slap’s a Slap: General John L. DeWitt and Four Little Words.” The Text Message Blog, National Archives and Records Administration.

Other Sources:

Adams, Ansel. Born Free and Equal: Photographs of the Loyal Japanese-Americans at Manzanar Relocation Center, Inyo County, California. New York: U.S. Camera, 1944. (Joyner Rare Collection: F870.J3 A57)

Goodman, Walter. The Committee: The Extraordinary Career of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1968. (Joyner Stacks E743.5 .G64)

Grodzins, Morton. Americans Betrayed: Politics and the Japanese Evacuation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1949. (Joyner Stacks D769.8.A6 G7)

Muller, Eric L. American Inquisition: The Hunt for Japanese American Disloyalty in World War II. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007. (Joyner Stacks D 769.8.A6 M85 2007)

Myer, Dillon, S. Uprooted Americans: The Japanese Americans and the War Relocation Authority during World War II. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1971. (Joyner Stacks D769.8.A6 M9) (Myer was head of the WRA from 1942-1946.)

Stone, Geoffrey R Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime from the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terrorism. New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 2004. (Joyner Stacks JC591 .S76 2004)