In the last several years, the rise of domestic right-wing extremism, in the form of the “alt-right” or white nationalism, has become a major issue in American politics. Events such as the violent “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, VA in August 2017, the October 2018 Pittsburgh synagogue massacre, and the August 2019 racist mass shooting in El Paso, TX prompted congressional committees to hold a number of hearings during 2019 investigating white nationalism and white supremacy.

These recent hearings are not the first occasion in which congressional committees have examined right-wing radicalism. In fact, congressional investigations of the radical right date back to the 1930s, and even helped lead to the creation of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Awareness of this background can help provide a deeper understanding of our current situation.

1. The 1930s and 40s

The rise of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party to power in Germany in 1933 inspired the creation of a number of radical right-wing movements here in the United States. This growth in domestic fascism and right-wing radicalism soon produced what historian Leo Ribuffo has called the “Brown Scare”: an often exaggerated fear of the threat posed by the radical right, in response to the alarming rise of the Third Reich in Europe and the frequently repellent activities of its supporters in the U.S. These concerns reached Congress, where, on March 20, 1934, the House of Representatives passed House Resolution 198 (H. Res. 73-2), which created a special committee to investigate:

“The extent, character, and objects of Nazi propaganda activities” in the U.S.; “The diffusion within the United States of subversive propaganda that is instigated from foreign countries and attacks the principle of the form of government as guaranteed by our Constitution”; and “All other questions in relation thereto” (78 CR 4934)

This Special Committee on Un-American Activities disbanded after releasing its report. However, in 1938, the body was reestablished as a continuing committee tasked with investigating “The diffusion within the United States of subversive and un-American propaganda that is instigated from foreign countries or of a domestic origin and attacks the principle of the form of government as guaranteed by our Constitution.” (83 CR 7568) Strengthened by this broader mandate, the committee would investigative both left-wing and right-wing extremism through the end of World War II. Made a standing committee in early 1945, HUAC as it became known soon focused its efforts on exposing real and alleged communist subversion.

Congressional Sources:

Investigation of Nazi and Other Propaganda, House Report No. 153, 74th Congress (74-1), Serial Set 9890 (1935) (Available in U.S. Congressional Serial Set; ECU users only)

Investigation of Nazi Propaganda Activities and Investigation of Certain Other Propaganda Activities. Public Hearings Before the Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Seventy-Third Congress, Second Session. 1934-35, 8. v. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4: Un 1: N 23)

Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Appendix. Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives. 1940-44, 9 v. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4.UN 1/2:UN 1/APP)

Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Executive Hearings. Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives. 1939-43, 7 v. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4.UN 1/2:UN 1/3)

Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Hearings Before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives. 1938-44, 17 v. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4.UN 1/2:UN 1)

2. The 1950s and 60s

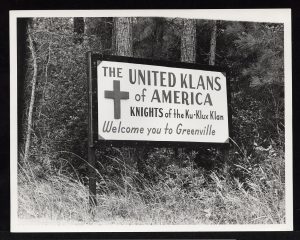

In the post-World War II period, HUAC mostly confined itself to investigating the Communist Party USA and other perceived sources of left-wing subversion. By the mid 1960s, however, with the civil rights revolution at its height, the committee was prompted to begin an investigation of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK).

HUAC began examining the KKK in the spring of 1965. A special subcommittee held public hearings from October 19, 1965 to February 24, 1966, and published a final report in December 1967. The committee found that there were a number of separate Klan organizations in the United States, of which the United Klans of America (UKA) was the largest and most powerful. October 1965 testimony by HUAC investigator Philip Manuel revealed that there were an estimated 112 UKA klaverns (local chapters) in North Carolina, making it, in Manuel’s words, “by far the most active state in terms of Klaverns and membership of the UKA.” (Activities of Ku Klux Klan in the U.S., pt. 1, p. 1553)

Of these 112 local Klan chapters, seven were found in Pitt County. Each of the counties adjacent to Pitt also contained at least one UKA klavern (Lenoir County had five).

Many historians have questioned the impact of HUAC’s investigation in bringing about the demise of the UKA. Scholar David Cunningham has argued, however, that it played an important role in generating negative publicity about the extent of UKA influence in North Carolina, thus prompting authorities in Raleigh to crack down on the organization.

Congressional Sources:

Activities of Ku Klux Klan Organizations in the United States. Hearings Before the Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Eighty-Ninth Congress, First (-Second) Session. 1965-66, 5 pts. + index (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4: Un 1/2: K 95; additional circulating copy in Joyner Docs Stacks: Y 4: Un 1/2: K 95)

The Present-Day Ku Klux Klan Movement. Report by the Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Ninetieth Congress, First Session. December 11, 1967. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 1.1/7: 90-377; additional circulating copy in Joyner NC Stacks: HS2330 .K63 A56)

3. The 1990s

The 1990s saw a further wave of concern regarding right-wing extremism. The spread of anti-government “militia” movements, in response to tragic incidents at Ruby Ridge, Idaho, and Waco, Texas, prompted fears of right-wing violence. These fears were magnified after the April 1995 destruction of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, one of the deadliest acts of domestic terrorism in American history.

In the wake of the Oklahoma City bombing, several congressional committees conducted hearings into the threat posed by right-wing domestic terrorists or by elements of the militia movement.

Congressional Sources:

The Militia Movement in the United States. Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Terrorism, Technology, and Government Information of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, One Hundred Fourth Congress, First Session. 1997. (Joyner Docs Stacks: Y 4.J 89/2:S.HRG.104-804)

Nature and Threat of Violent Anti-Government Groups in America. Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Crime of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, One Hundred Fourth Congress, First Session. 1996. (Joyner Docs Stacks: Y 4.J 89/1:104/51)

Terrorism in the United States: The Nature and Extent of the Threat and Possible Legislative Responses. Hearing Before the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, One Hundred Fourth Congress, First Session. 1997. (Joyner Docs Stacks: Y 4.J 89/2:S.HRG.104-757)

4. 2019 Congressional Committee Hearings on Right-Wing Extremism

Confronting the Rise of Domestic Terrorism in the Homeland: Hearing Before the Committee on Homeland Security, House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixteenth Congress, First Session. May 8,2019.

–Committee Website

-Published Transcript

Confronting Violent White Supremacy (Part III): Addressing the Transnational Terrorist Threat. Joint Hearing Before the Subcommittee on National Security and the Subcommittee on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties of the Committee on Oversight and Reform, House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixteenth Congress, First Session. September 20, 2019.

–Committee Website

–Published Transcript

Confronting White Supremacy (Part I): The Consequences of Inaction. Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties of the Committee on Oversight and Reform, House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixteenth Congress, First Session. May 15, 2019.

–Committee Website

–Published Transcript

Confronting White Supremacy (Part II): Adequacy of the Federal Response. Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties of the Committee on Oversight and Reform, House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixteenth Congress, First Session. June 4, 2019.

–Committee Website

–Published Transcript

Countering Domestic Terrorism: Examining the Evolving Threat. Hearing Before the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, United States Senate, One Hundred Sixteenth Congress, First Session. September 25, 2019.

–Committee Website

–Published Transcript

Hate Crimes and the Rise of White Nationalism. Hearing Before the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixteenth Congress, First Session. April 9, 2019.

–Committee Website

Meeting the Challenge of White Nationalist Terrorism at Home and Abroad. Joint Hearing Before the Subcommittee on the Middle East, North Africa, and International Terrorism of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, with the Subcommittee on Intelligence and Counterterrorism of the Committee on Homeland Security, House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixteenth Congress, First Session. September 18, 2019.

–Committee Website

–Published Transcript

Additional Sources:

Belew, Kathleen. Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018. (Joyner Stacks: HS2325 .B45 2018)

Churchill, Robert H. To Shake Their Guns in the Tyrant’s Face: Libertarian Political Violence and the Origins of the Militia Movement. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2009. (Joyner Stacks: HN90.R3 C485 2009)

Cunningham, David. Klansville, U.S.A. The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights-Era Ku Klux Klan. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. (Joyner NC Stacks: HS2330 .K63 C75 2013)

Hawley, George. Making Sense of the Alt-Right. New York: Columbia University Press, 2017. (Joyner Stacks: E184.A1 H3377 2017)

Neiwert, David. Alt-America: The Rise of the Radical Right in the Age of Trump. London: Verso, 2017. (Joyner Stacks: E184.A1 N365 2017)

Ribuffo, Leo P. The Old Christian Right: The Protestant Far Right from the Great Depression to the Cold War . Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1983. (Joyner Stacks: E806 .R47 1983)

Smith, Geoffrey S. To Save a Nation; American Countersubversives, the New Deal, and the Coming of World War II. New York: Basic Books, 1973. (Joyner Stacks: E806 .S684)

Wade, Wyn Craig. The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1987. (Joyner Stacks: HS2330.K63 W33 1987)