The current film Judas and the Black Messiah depicts the life and death of Fred Hampton, a leader of the Chicago branch of the Black Panther Party (BPP). Hampton was killed on December 4, 1969, in a raid by Chicago police officers on the apartment where he was staying with eight other members of the BPP. At the time, the Chicago Police Department and the Illinois State’s Attorney’s Office claimed the police shootings of Hampton and another Panther killed during the raid were acts of justified self-defense. Subsequent investigation made it abundantly clear that these explanations were false.

The Black Panther Party

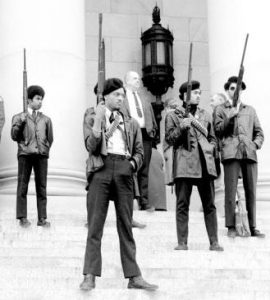

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded in Oakland, CA, in late 1966, and soon spread to a number of urban areas with large African-American populations. From its beginnings the BPP saw itself as a revolutionary movement that embraced Maoism and, if necessary, armed resistance to local, state, and federal authorities. They regarded racism as endemic to the American socio-political system, and believed that only a total rejection of that system could free African-Americans from its effects. The various BPP chapters stockpiled weapons, often confronted police while armed, and cultivated a militant, paramilitary culture in their ranks. The movement’s rhetoric was often violent, and glorified if not incited anti-police violence.

The BPP’s militantly anti-police posture was very much a response to the all-too widespread police violence against African-American communities. Not simply acts of police brutality and even killing, but also daily acts of harassment and petty humiliation. Coupled with the widespread urban unrest of the 1960s, and rising overall crime rates, tensions between many urban police departments and African-American communities reached the breaking point. As a 1973 independent report on the killing of Fred Hampton described it, there was now an “atmosphere of anger, fear, and mutual hostility…between black Chicagoans and the police.” The report continued:

That such an atmosphere existed could come as no surprise to

anyone even casually familiar with the state of police-community

relations in black areas of American cities at that time. Chicago’s

experience during the late 1960s may have been especially violent and

tense, but it was fundamentally no different from the situation that

prevailed in almost every major urban center in the country. (Wilkins and Clark, Search and Destroy, 28)

Through their often violent words, and occasional actions, the BPP both reflected this dynamic and contributed to it. Their radical ideology and rhetoric soon made them a major target of local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover described the BPP as “without question…the greatest threat to the

internal security of the country [among] violence-prone black-extremist groups.” (Quoted in Wilkins and Clark, Search and Destroy, 11)

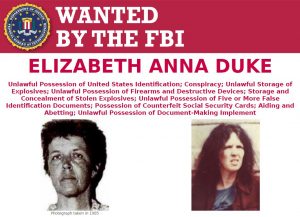

At Hoover’s direction, the Panthers soon became one of the top targets of the FBI’s controversial Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO). Initiated in 1956, expanded starting in 1965, and continued until 1971, COINTELPRO was designed not simply to monitor groups suspected of seeking the violent overthrow of the U.S. government, but sought to actively disrupt and sabotage their operations, through the use of informants and disinformation. The BPP branch in Chicago, established in 1968, soon became a major COINTELPRO focus.

The Killing of Fred Hampton

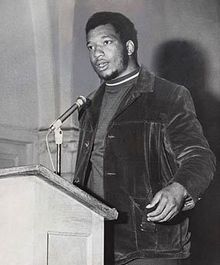

Fred Hampton, eloquent and charismatic, soon emerged as the leader of the BPP in Chicago. While using rhetoric typical of the Panther movement, most of his activities involved non-violent organizing and community outreach efforts. Over the course of 1969, however, a number of violent incidents between Panthers and Chicago police took place, often instigated by the latter. According to a May 1970 federal grand jury report, as a result of these incidents “two police and one Panther were killed; fourteen police and four Panthers were wounded or injured; and there had been over sixty arrests of Panthers for violations ranging from attempted murder and kidnapping to minor traffic violations.” (United States District Court, Report, 12)

The evidence makes clear that, by the time of the December 4th raid, Chicago police saw themselves as at war with the BPP. The raid itself was prompted in part by information provided by the FBI, and facilitated by an FBI informant. Of the nine individuals in the apartment at 2337 W. Monroe Street, Hampton and another Panther, Mark Clark, were killed, and four others were wounded. Two policemen suffered light injuries. The police and state’s attorney insisted that the deaths and injuries were the result of the officers being met with armed resistance while trying to serve a lawful warrant. All seven survivors were charged, with a total of 31 criminal counts between them.

The immediate aftermath of the raid sparked a huge outcry, especially among the African-American community. An estimated 5,000 mourners came to Fred Hampton’s funeral. Almost immediately, the Panthers questioned the official version of events. Evidence soon bore out their complaints. An FBI forensics analysis showed that only one shot was fired by the Panthers at 2337 W. Monroe. By contrast, the police fired as many as 99 rounds. This clearly refuted the claims of a shootout, and the charges against the survivors were soon dismissed. Hampton, who was unconscious and possibly drugged during the raid, was shot four times while laying in bed.

The independent 1973 investigation concluded that:

Every indication is that the raid, contrary to its stated objectives, was

conceived and planned as an armed confrontation with leaders of the

Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party under circumstances in which the planners of the raid knew-or should have known-that loss of life was almost inevitable. (Wilkins and Clark, Search and Destroy, 237-8)

The killing of Fred Hampton and the federal/state law enforcement campaign against the BPP reflect a number of strands of American history, including racism, police brutality, and the often violent tumult America experienced during the late 1960s. It also marked perhaps the culmination of the 20th Century countersubversive mindset that saw almost any form of social protest as simply the product of radical subversion, to be suppressed by extralegal and even unconstitutional means if necessary. As civil rights leader Reverend Ralph Abernathy stated at Fred Hampton’s funeral:

If they can do this to the Black Panthers today, who will they do it to

tomorrow? If they succeed in repressing the Black Panthers, it won’t be long

before they crush any party in sight-maybe your party, maybe my party.

(Quoted in Wilkins and Clark, Search and Destroy, 5)

CWIS Sources:

Black Panther Party. Hearings Before the Committee on Internal Security, House of Representatives, Ninety-First Congress, Second Session. 1970-71, 4 pts. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4: In 8/15: B 56)

The Black Panther Party: Its Origin and Development as Reflected in its Official Weekly Newspaper The Black Panther, Black Community News Service: Staff Study. Committee on Internal Security, House of Representatives, Ninety-First Congress, Second Session. 1970. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4: In 8/15: B 56/2)

Domestic Intelligence Operations for Internal Security Purposes: Part 1: Hearings Before the Committee on Internal Security, House of Representatives, Ninety-Third Congress, Second Session. 1974. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4: In 8/15:IN 8/4/PT.1)

-Discusses FBI investigations of alleged domestic subversion, including the BPP.

Extent of Subversion in the New Left, Part 4: Testimony of Charles Siragusa and Ronald L. Brooks: Hearings Before the Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Ninety-First Congress, Second Session. June 10, 1970. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4.J 89/2:L 52/3/ PT. 4)

-The witnesses were representatives of the Illinois Crime Investigating Commission. Their testimony includes 10 references to Fred Hampton.

Gun-Barrel Politics, the Black Panther Party, 1966-1971. Report by the Committee on Internal Security, House of Representatives, Ninety-Second Congress, First Session. August 18, 1971. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 1.1/8: 92-470)

Riots, Civil and Criminal Disorders, Part 20: Hearings before the United States Senate Committee on Government Operations, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Ninety-First Congress, First Session. 1969. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4.G 74/6:R 47/PT. 20)

-Focuses on the alleged role of the Black Panthers in fomenting urban unrest. Includes 14 references to Fred Hampton

Riots, Civil and Criminal Disorders, Part 25: Hearings before the United States Senate Committee on Government Operations, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Ninety-First Congress, Second Session. 1970. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4.G 74/6:R 47/PT. 25)

-Includes testimony on the Black Panthers and the situation in the south side of Chicago.

Additional Federal Government Sources:

FBI FOIA Vault: Black Panther Party.

-“This release consists of Charlotte’s file on BPP activities from 1969 to 1976.”

FBI FOIA Vault: Fred Hampton.

-Contains material on the investigation into Fred Hampton’s killing.

FBI FOIA Vault: Stokely Carmichael.

Intelligence Activities Senate Resolution 21: Vol. 6: Federal Bureau of Investigation. Hearings before the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, United States Senate, Ninety-Fourth Congress, First Session. 1975. (Joyner Docs Stacks: Y 4.IN 8/17:IN 8/ V. 6)

-Exhaustive investigation into COINTELPRO and other FBI domestic surveillance activities.

National Archives and Records Administration: African American Heritage: Fred Hampton (August 30, 1948 – December 4, 1969)

National Archives and Records Administration: Rediscovering Black History: Fred Hampton: Vanguard Revolutionary. December 4, 2019.

United States District Court, Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division. Report of the January 1970 Grand Jury. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1970. (Available via Internet Archive)

Additional Sources:

Austin, Curtis J. Up Against the Wall: Violence in the Making and Unmaking of the Black Panther Party. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2006. (Joyner Stacks: E185.615 .A88 2006; Click here for E-book – ECU users only)

The Black Panthers Speak. ed. Philip S. Foner. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2014. (Joyner Stacks: E185.615 .B54646 2014)

Blackstock, Nelson. Cointelpro: The FBI’s Secret War on Political Freedom. New York: Vintage Books, 1976. (Joyner Stacks: HV8141 .B6 1976)

Haas, Jeffrey. The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books/Chicago Review Press, 2009. (E-book on order)

Seattle Black Panther Party — History and Memory Project:

-Highly detailed historical resource, featuring lengthy narratives, photographs, newspaper articles and other primary documents and oral histories. Includes transcripts and exhibits from the 1971 HCIS hearing into the Seattle-area Panthers. Part of the University of Washington’s Pacific Northwest Labor and Civil Rights Projects.

Taylor, Flint. The Torture Machine: Racism and Police Violence in Chicago. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2019. (Joyner Stacks: HV8148 .C42 T39 2019)

Wilkins, Roy and Ramsey Clark. Search And Destroy: A Report by the Commission of Inquiry into the Black Panthers and the Police. New York: Metropolitan Applied Research Center, 1973. (Available via Internet Archive)

-Independent report on the December 4, 1969 raid in which Hampton was killed.

Williams, Jakobi. From the Bullet to the Ballot: The Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party and Racial Coalition Politics in Chicago. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. (Joyner Stacks: F548.9 .N4 W55 2013)