One consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the numerous charges and counter-charges regarding the origins of the virus. In particular, the allegations by the Trump administration that the pandemic was the result of research done at a scientific laboratory in Wuhan, China that then leaked out. Both China and Russia have countered with claims that the COVID pandemic was actually created, purposefully or not, by the United States.

Such competing political claims regarding the origins of diseases are nothing new. They were, in fact, a regular staple of the Cold War information and propaganda contest. The USSR and its allies from the early 1950s regularly blamed domestic diseases and crop failures on American efforts at biological warfare (BW). Most famously, the 1980s KGB active measures campaign “Operation Denver” claimed that the AIDS virus was created at a U.S. Army biological research facility at Fort Detrick, MD. In turn the U.S. alleged that a 1979 anthrax outbreak in the Soviet city of Sverdlovsk was the result of a biological warfare accident (true), and that in the early 1980s the USSR used a mycotoxin dubbed “yellow rain” in Afghanistan and Southeast Asia (unproven: likely false.)

The earliest major Cold War controversy involving allegations of BW was a series of claims by China and North Korea in 1951-52 that the United States employed biological weapons during the Korean War. While vehemently denied by the US, these charges were treated as credible by much of the left in Western Europe, and by a large part of what would soon become known as the Third World. Most western scholars have rejected the allegations, noting that credible evidence of US BW use is lacking. Post-Cold War Soviet and Chinese revelations, in particular, have cast tremendous doubt on the communist charges.

Unit 731 and the Origins of the Campaign

It is difficult to understand the Korean War BW controversy without putting it in the context of Japan’s WWII biological weapons program. Imperial Japan had an extensive BW program between 1932-45, with its largest, most infamous element, Unit 731, located in Manchuria, directly north of the Korean peninsula. According to scholar Sheldon H. Harris, Japan’s horrific BW activities, both gruesome experiments and actual use of bacteriological weapons, killed some 250,000 people in China and Manchuria. After the war, many of the leading figures in Japan’s BW program were captured by American occupation authorities. This included the longtime head of Unit 731, General Shiro Ishii. Shamefully, the American authorities granted Ishii and his colleagues immunity from prosecution, in return for providing US intelligence with the results of their research.

In contrast, the USSR, in December 1949 staged a trial at Khabarovsk in the Soviet Far East, in which 12 captured Japanese officers tied to Unit 731 were tried for war crimes. On the one hand, the trial did much to expose the terrible truth of Japan’s BW program. However, it was also a propaganda event designed to embarrass the United States and Japan. In addition to noting that Ishii and his colleagues were protected by the U.S., the Soviets claimed that Ishii was continuing his BW efforts at American behest, and even demanded the extradition of Emperor Hirohito for complicity in Unit 731’s activities.

The crimes of Unit 731 played a key part in the communist allegations of American BW use in Korea. Many of the reported biological attacks directly matched Japanese methods used during WW II. In addition, Unit 731 was prominently featured in communist propaganda even before the first allegations of American bacteriological warfare were made. In the words of scholar Milton Leitenberg:

In the first five months of 1951, the Chinese press and radio made repeated references to Gen. Ishii and the Japanese wartime BW programs, the Khabarovsk trial, Gen. Ishii’s subsequent employment by the United States, and the claim that the United States was preparing to use BW in the Korean War.

(Leitenberg, “New Russian Evidence,” 188)

Two Waves of Charges

The Korean War began on June 25, 1950, when communist North Korea invaded pro-western South Korea. As noted above, after communist China entered the war in late 1950 to save North Korea from defeat, Chinese media outlets offered frequent warnings that the US was preparing to resort to BW. It was not until May 8, 1951, that the first allegation of actual BW use was made, when North Korea’s foreign minister accused the US of having spread smallpox in parts of North Korea. Occasional Chinese and North Korean claims of American biological weapons use continued into the summer of 1951. In addition to BW, the Chinese also claimed during this period that US forces employed poison gas.

The main communist campaign claiming that America was using BW came in the winter and spring of 1952. On February 22, 1952, the North Korean Foreign Minister once again accused the United States of using biological weapons. This time, the allegations were that American planes dropped a variety of insects over North Korea, carrying diseases such as plague, anthrax, and cholera. The methods described were virtually identical to those used by the Japanese in China during WWII. The charges were soon echoed by the Chinese, who claimed that US aircraft were engaged in such activities over both North Korea and northeast China, with American planes allegedly flying about 1,000 BW-related sorties over the latter region between January-March 1952. As evidence, the Chinese produced insects they claimed were dropped from US aircraft, American leaflet bombs that they claimed had been used to deliver these insects, and coerced interrogations from several dozen captured American airmen.

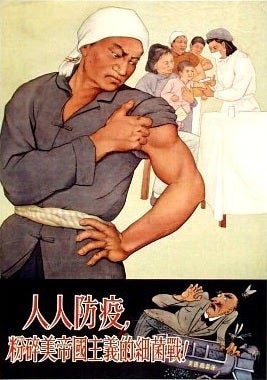

By-mid March, the two communist countries, joined by their patron the Soviet Union, had embarked on a massive propaganda campaign based on the BW charges. The Soviets, through their front organization the World Peace Council, stirred up anti-American sentiment in western Europe and elsewhere. China, while spurning offers of an investigation by the International Red Cross or World Health Organization, assembled two investigative committees composed of sympathetic individuals that released reports supporting the communist allegations. Within China, the Maoist regime used the hysteria whipped up by the BW charges to launch a “patriotic hygiene” campaign that mobilized much of the Chinese population in support of a sweeping vaccination and public health effort.

Starting in early March, the United States vehemently denied the communist allegations. The biological warfare controversy began to fade by the fall of 1952, and soon became a historical footnote with the Korean War armistice of May 1953.

Recent Revelations

Since the Korean War, the question of whether the United States engaged in biological warfare has occasionally fostered controversy. China and North Korea insist to this day that the BW allegations were true. Most western historians disagree. A small group of radical left western scholars have periodically tried to validate the communist charges and prove the US guilty of employing BW in Korea. The most recent effort in this regard is writer Nicholson Baker’s 2020 book Baseless. The book summarizes the case for American guilt, but is ultimately shoddy and unconvincing.

The bulk of the evidence strongly indicates that the communist charges are false if not outright fabricated. For one thing, there is no direct documentary evidence that America tried to employ BW in Korea, While the US did have a biological warfare program at the time, scholars such as Conrad Crane have shown that America lacked the ability to wage a campaign such as the Chinese and North Koreans alleged. Also, there were no actual widespread epidemics reported in China, and none in North Korea that couldn’t be explained by natural methods of disease spread. The only evidence produced in support of the charges was by the communists themselves. The “confessions” by American POWs were repudiated as soon as those men returned to the United States.

The most conclusive evidence refuting the communist allegations emerged in the 1990s from China and the former Soviet Union. In 1997, Wu Zhili, the head of medical services for Chinese forces during the Korean War, wrote a brief memoir reflecting on his 1952 investigation of alleged US BW use. Discovered after his death in 2008, the document was published in a Chinese publication in 2013:

(1) Imperialism is capable of carrying out all manner of evils, and bacteriological war is not an exception. (2) Severe winter, however, is not a good season for conducting bacteriological war. When the weather is cold the mobility of insects is weakened, and is not conducive to bacteria reproduction. (3) Dropping [objects] on the front line trenches, where there are few people and sickness does not spread easily, and where the U.S. military’s trenches are not more than ten meters away, allows for the possibility of ricocheting. (4) Korea already had an epidemic of lice-borne contagious diseases. All the houses in the cities and towns had been burned down, and the common people all lived in air-raid shelters. Their lives are already difficult, but the Korean people are extremely tenacious and bacteriological warfare cannot be the greater disaster that forces them to surrender. (5) Our preliminary investigation still could not prove that the U.S. military carried out bacteriological warfare.

(“Wu Zhili, ‘The Bacteriological War of 1952 is a False Alarm'”)

In conclusion, Wu wrote, “the bacteriological war of 1952 was a false alarm.”

Even more damning, in 1998 a Japanese newspaper obtained copies of a number of high-level Soviet documents from April and May 1953 concerning the Korean War BW allegations. The documents show that the senior leadership of the Soviet Communist Party, who had just taken power after the March 1953 death of Joseph Stalin, quickly and unabashedly labeled the allegations as fabricated. Perhaps the most important document is a May 2, 1953 message from the new Soviet leadership directly to Mao Tse-Tung:

The Soviet Government and the Central Committee of the CPSU were misled. The spread in the press of information about the use by the Americans of bacteriological weapons in Korea was based on false information. The accusations against the Americans were fictitious.

(Resolution of the Presidium of the USSR Council of Ministers)

While it appears that the Chinese and North Koreans may have genuinely believed in early 1952 that the United States was using BW against them, they soon realized that this was not the case. Nonetheless, they cynically continued making the charges, for purposes of international propaganda and domestic mobilization. This would be only one of many such situations during the Cold War in which real and fictitious incidents of disease and BW activity would become tools of global political warfare.

Sources:

Baker, Nicholson. Baseless: My Search for Truth in the Ruins of the Freedom of Information Act. New York: Penguin Press, 2020.

Crane, Conrad C. “‘No Practical Capabilities’: American Biological and Chemical Warfare Programs During the Korean War,” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 45, no. 2 (Spring 2002): 241-249. DOI: 0.1353/pbm.2002.0024.

Harris, Sheldon H. Factories of Death: Japanese Biological Warfare, 1932-1945, and the American Cover-Up. New York: Routledge, 2002. (Joyner Stacks: DS777.533.B55 H37 2002)

Jager, Sheila Miyoshi. Brothers at War: The Unending Conflict in Korea. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2013. (On order for Joyner Library)

Leitenberg, Milton. China’s False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United States during the Korean War. Cold War International History Project Working Paper #78, March 2016.

Leitenberg, Milton. “New Russian Evidence on the Korean War Biological Warfare Allegations: Background and Analysis.” Cold War International History Project Bulletin 11 (Winter 1998): 180-199.

Materials on the Trial of Former Servicemen of the Japanese Army Charged with Manufacturing and Employing Bacteriological Weapons. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1950. (Joyner Stacks: KLA44.Y36 Y3613 1950)

Regis, Ed. The Biology of Doom: The History of America’s Secret Germ Warfare Project. New York: Henry Holt, 1999. (Joyner Stacks: UG447.8 .R44 1999)

“Resolution of the Presidium of the USSR Council of Ministers about Letters to the Ambassador of the USSR in the PRC, V.V. Kuznetsov and to the Charge d’Affaires for the USSR in the DPRK, S.P. Suzdalev,” May 02, 1953, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Archive of the President of the Russian Federation. Translated by Kathryn Weathersby. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/112030

Wilson Center Digital Archive: ‘Korean War Biological Warfare Allegations.”

-“A collection of primary source documents related to the Korean War. Obtained largely from Russian archives, the documents include reports on Chinese and Soviet aid to North Korea, allegations that America used biological weapons, and the armistice.”

“Wu Zhili, ‘The Bacteriological War of 1952 is a False Alarm’,” September 1997, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Yanhuang chunqiu no. 11 (2013): 36-39. Translated by Drew Casey. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/123080