Note: Dr. David Cunningham, author of Klansville USA: The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights-Era Ku Klux Klan, the definitive history of the Klan in eastern North Carolina, is speaking at Sheppard Memorial Library on Wednesday, October 16, at 4:30 PM. Anyone interested in this topic is strongly encouraged to attend. Dr. Cunningham’s visit is sponsored by the ECU Department of Sociology.

1. HUAC Turns its Attention to the Klan

By 1965, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) had grown increasingly unpopular and controversial. As the transformation of American culture and society in the 1960s unfolded, HUAC increasingly looked like an anachronism at best and a serious threat to civil liberties at worst. Despite its origins as a special committee to investigate Nazi propaganda in 1934 and its periodic inquiries into domestic Nazi and fascist groups in the 1930s and 40s, by the late 1950s HUAC had adopted the position that it was only empowered to investigate the Communist Party (CPUSA) and other left-wing groups believed to be “subversive” or “un-American.” This bias was one of the major factors contributing to the growing outcry against HUAC and other congressional countersubversive committees. Thus, by 1965 the committee now welcomed the opportunity to investigate a right-wing extremist organization. With the civil rights revolution at its height, just such a target was readily at hand: the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK).

HUAC had begun a preliminary inquiry into the Klan in late 1964. On March 30, 1965, just five days after the Klan murdered Viola Liuzzo, a Detroit woman working with the civil rights movement in Alabama, HUAC voted unanimously to launch a full investigation of the KKK. Interestingly, many civil rights organizations opposed HUAC’s investigation, fearing that it would be turned against themselves instead of the Klan.

The most important driving force behind HUAC’s decision to initiate a full-scale inquiry into the KKK was one of the committee’s newest members, Rep. Charles L. Weltner (D-GA). Weltner, representing a district from Atlanta, was the only representative from a former Confederate state to vote for passage of the final version of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. He joined HUAC in 1965 eager to use its broad investigative powers against the Klan.

2. The Klan in Eastern North Carolina

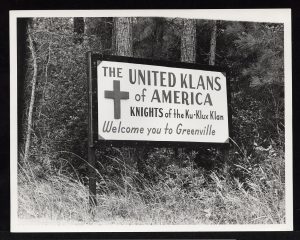

HUAC began its hearings into the KKK in October 1965. A special subcommittee held hearings from October 19, 1965 to February 24, 1966, and published a final report in December 1967. The committee found that there were a number of separate Klan organizations in the United States, of which the United Klans of America (UKA) was the largest and most powerful. October 1965 testimony by HUAC investigator Philip Manuel revealed that there were an estimated 112 UKA klaverns (local chapters) in North Carolina, making it, in Manuel’s words, “by far the most active state in terms of Klaverns and membership of the UKA.” (Activities of Ku Klux Klan in the U.S., pt. 1, p. 1553)

Of these 112 local Klan chapters, seven were found in Pitt County. Like all UKA klaverns, the ones in Pitt County had innocuous sounding cover names. According to Manuel’s testimony, these seven klaverns were the following:

- Benevolent Association No. 53 (Greenville)

- Ogden Christian Fellowship Club No. 53 (Greenville)

- The Benevolent Association (Winterville)

- Pitt County Improvement Association No. 37 (Farmville)

- Ayden Christian Fellowship Club (Ayden)

- Grifton Christian Society (Grifton)

- Fountain Klavern (cover name not given)

Each of the counties adjacent to Pitt also contained at least one UKA klavern (Lenoir County had five). In short, as noted journalist Stewart Alsop wrote in a April 1966 profile of the Klan in North Carolina for the Saturday Evening Post: “The hard core of the Klan is in the flat, sandy, cotton-and-tobacco country in the eastern part of the state.” (Alsop, “Portrait”)

3. HUAC Investigates the Klan in Pitt County

With the UKA heavily active in North Carolina, and in eastern North Carolina in particular, it is no surprise that HUAC’s investigation would eventually impact Greenville and Pitt County. Two witnesses, one non-cooperative, one very much cooperative, would travel from Pitt County to testify before HUAC.

James Huey “Sonny” Fisher was a native of Farmville, where he was a leader of the Pitt County Improvement Association (aka: the Farmville UKA Klavern). He also served as the Grand Klokkard (state lecturer) for the North Carolina Realm of the UKA. As such, he was one of a number of North Carolina Klan leaders subpoenaed to testify before HUAC. He duly appeared before the committee on October 22, 1965, where he was accompanied, as were most UKA witnesses, by Raleigh-based attorney Lester V. Chalmers, Jr. During his testimony, Fisher politely declined to answer any questions, nor produce any requested documents, citing his rights under the 5th, 1st, 4th, and 14th amendments to the Constitution – as did most UKA witnesses – after which Fisher was excused . (Activities of Ku Klux Klan in the U.S., pt. 1, p. 1869-1876)

The testimony of the other witness from Pitt County, George Leonard Williams, was much more informative in nature. A former Klansman and resident of Greenville, Williams appeared before HUAC on January 28, 1966. In his testimony, Williams recounted that he had joined the Greenville Klavern (Benevolent Association No. 53) on July 28, 1965, In October, he switched to the Pactolus Klavern (Pactolus Hunting Club), where he would remain as a member until he left the Klan in mid-November 1965. Williams testified that he was motivated to join the Klan by its strident opposition to civil rights and racial integration. On August 31, 1965, he was shot and wounded in an altercation with an African-American man in Plymouth, NC, where he was one of nearly 1,000 UKA members, nearly all from outside Plymouth, who made a show of force in response to local civil rights demonstrations. This incident, along with a violent incident between members of the Greenville and Pactolus Klaverns and perceived financial irregularities, persuaded Williams to leave the Klan. Subsequent threats made against him by the Klan motivated him to appear before HUAC.

Williams testified that the Klan had about 40 active members in the Greenville area, with about 340 listed on the books. He explained this discrepancy by stating that “Most of the Klan, the people that get into the Klan go and join, and after they get in and find out what they are in, they don’t never come back no more.” (Activities of Ku Klux Klan in the U.S., pt. 3, p. 2891) According to his account, the Pactolus Klavern itself split off from the UKA to join a local Klan offshoot.

While HUAC conducted a number of investigations pertaining to North Carolina, even holding hearings in Charlotte in 1956 on the CPUSA presence in the state, the 1965-66 Klan investigation is the only one in the committee’s history that directly involved Greenville and Pitt County.

The author gratefully acknowledges the cooperation of Matt Reynolds, Digital Collections Librarian, with the research for this post.

CWIS Sources:

Activities of Ku Klux Klan Organizations in the United States. Hearings Before the Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Eighty-Ninth Congress, First (-Second) Session. 1965-66, 5 pts. + index (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4: Un 1/2: K 95; additional circulating copy in Joyner Docs Stacks: Y 4: Un 1/2: K 95)

The Present-Day Ku Klux Klan Movement. Report by the Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Ninetieth Congress, First Session. December 11, 1967. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 1.1/7: 90-377; additional circulating copy in Joyner NC Stacks: HS2330 .K63 A56. Also available in U.S. Congressional Serial Set; ECU users only)

Additional Sources:

Alsop, Stewart. “Portrait of a Klansman.” Saturday Evening Post, 239, 8 (April 9, 1966): 23-27.

Cunningham, David. Klansville USA: The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights-Era Ku Klux Klan. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. (Joyner NC Stacks HS2330 .K63 C75 2013)

Goodman, Walter. The Committee: The Extraordinary Career of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1968. (Joyner Stacks E743.5 .G64)

Oakley, Christopher Arris, Matthew Reynolds and Dale Sauter. Greenville in the 20th Century. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2013. (Joyner Special Collections Ref. F264.G8 O25 2013)