The week of October 25-31 is National Lead Poisoning Prevention Week (NLPPW), a time for public and environmental health professionals to spread awareness and educate the public about lead poisoning prevention strategies (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020). The main goal of NLPPW is to reduce childhood lead exposure, a condition affecting millions of children each year (WHO, 2019). According to the CDC, children under the age of six are at highest risk for lead poisoning due to their developing bodies and the likelihood of putting hands (potentially contaminated with lead particles) into their mouths (CDC, 2020). Also, lead absorption occurs at a much faster rate in children than in adults (Wani et al., 2015). Other individuals at high risk for health impacts of lead poisoning include pregnant women, refugees, and children that have immigrated into the United States from areas where lead exposure is common (CDC, 2020).

In preventing childhood lead exposure, it is important to understand sources and routes of exposure. Inhalation of lead particles and ingestion of lead-contaminated substances are two common lead exposure routes. Lead particles can be released into the air during lead paint removal, using leaded gasoline, and burning of lead-based materials during smelting and recycling (WHO, 2019). Ingestion typically occurs when an individual drinks water from leaded pipes or eats food from lead-coated containers (WHO, 2019).

Primary Exposure Prevention

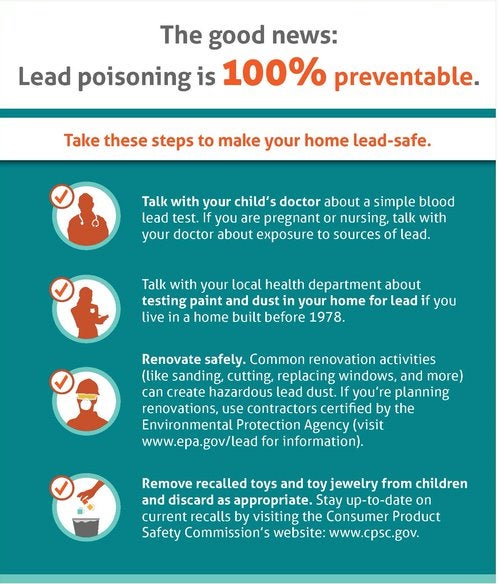

Physically removing lead hazards from a child’s environment is one of the first steps in preventing lead exposure. This is the most effective way to reduce the possibility of a child contacting lead-based substances (CDC, 2020). Recommendations for primary prevention also include good hand hygiene (frequent handwashing), frequent vacuuming (to eliminate lead particles in the home and other environments), increasing calcium and iron intake, and teaching children to avoid putting their hands in their mouths (Wani et al., 2015).

Secondary Exposure Prevention

For children or others suspected of lead exposure, blood testing can be conducted to determine degree of lead poisoning. Investigation and subsequent removal of the lead source are essential for preventing further exposure. Follow up blood testing can be conducted to mitigate potential further negative health outcomes (CDC, 2020).

No level of lead exposure is safe for individuals of any age. Even the lowest lead concentrations in a child’s blood may harm their health (WHO, 2019). Common health effects from lead exposure include behavioral and cognitive deficits like reduced intelligence quotient (IQ), reduced attention span, and antisocial tendencies. Anemia, hypertension, reproductive toxicity, and renal impairment may also occur after prolonged lead exposure. Serious consequences of lead exposure on children include coma, convulsions, and even death (WHO, 2019).

The Lead Contamination Control Act of 1988 mandates that the CDC must develop programs and policies to prevent childhood lead exposure, educate the public and medical providers about lead poisoning, work side-by-side with local and state health departments in lead screening and community outreach, and conduct research to determine effective prevention strategies on all levels of government (CDC, 2020). Lead poisoning is 100% preventable and it is our duty as health professionals to protect public health by educating the public on preventing lead exposure in children and others.

Photo source: hud.gov

Photo source: hud.gov

Photo Source: CDC Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention

Photo Source: CDC Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). National Lead Poisoning Prevention Week. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/national-lead-poisoning-prevention-week.htm

Wani, A.L., Ara, A., Usmani, J.A. (2015). Lead Toxicity: A Review. Interdisciplinary Toxicology, 8(2):55-64. doi:10.1515/intox-2015-0009

World Health Organization. (2019). Lead Poisoning and Health. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning-and-health

*This article is contributed by MS Environmental Health student, Jordan Mazzara.