Kari Carr

She was 14 years old and running away from abuse. Within 24 hours a man approached her and asked if she was hungry and needed a place to stay. She hadn’t eaten in days and it had just begun to rain. He seemed nice. He was well dressed. It seemed a better alternative to staying on the streets. The first few weeks were amazing. He seemed to love her, and she loved him. She had never known so much kindness—food, trips out to the mall, even to the movies. Then one day he tells her that he needs help with the rent. She’d only have to do it one time and she knows the guy—it’s a friend. Just this once, if you love me. But it wasn’t just once and it was with dozens of different men, hundreds over the years. Four years go by. She’s 18, a legal adult. What is she supposed to do now? She has no job experience. No education beyond 9th grade and the mindset that she’s only good for one thing and that no one wants her anyway.

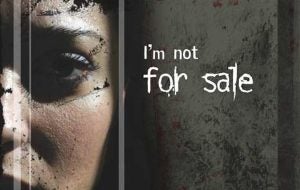

Some people argue that sex work can be liberating and that not all prostitutes are victims of human trafficking—some prostitutes are instead willing participants. I argue, however, that the system of prostitution requires objectification of humans and the commoditization of these “human objects.” This modern system of slavery commoditizes human beings while humans who maintain autonomy consume the commoditized bodies. With exploitation at its core, “sex work” cannot serve as a means of empowerment or liberation. And for those in favor of “sex work” as a means of false liberation I stand by the statement that personal empowerment does not take precedence over another person’s exploitation.

Human trafficking involves the objectification and subsequent commoditization of a subset of the population — the rest of the population that maintains agency, has the power to purchase/receive bodies that are an economic hybrid of a gift and a commodity. Furthermore, individuals with less autonomy (i.e. children, homeless individuals, adults with a history of childhood abuse, financially vulnerable individuals, etc.) are more likely to be victimized in systems of sexual exploitation. Commodity is defined as “a raw material or primary agricultural product that can be bought and sold, such as copper or coffee.” Commoditization refers to something, such as a person, being devalued and objectified into an everyday object such as coffee.

All value is created, not intrinsic, and when humans are devalued to mere objects, this is creation not human nature. Trafficking victims belong to their primary traffickers, and whether a “gift” to a friend or a “business transaction” the trafficked seem to be an economic hybrid of gift and commodity. Igor Kopytoff writes, “Commoditization, then, is best looked upon as a process of becoming, rather than as an all-or-none state of being.” This combined with the role of culture in decommoditization and commoditization explains how human trafficking allows some people to be commodities and others to be autonomous humans in society. Actual behavior often outweighs laws or otherwise expected behaviors in society. Although prostitution is illegal in most U.S. states, for example, the culture allows the purchase of humans for sex to continue. Kopytoff also proposes that the career of slaves involve successive phases of original commoditization, followed by decommoditization, and then there is a possibility of recommoditization. This means that once a human becomes a commodity they then begin to garner a social identity in the society they have been sold into (i.e. prostitute, whore, etc.). These individuals, however, are part human and part object at this stage, and this step then allows for easier consumption from people with full autonomy (purchasers). There is enough humanization present to rationalize that they “want” to be there, but enough dehumanization present to rationalize that the trafficked objects cannot say “no” to their traffickers. Therefore, people in the sex industry do not have agency. Buyers can choose to pay less than the agreed upon price, not pay the prostitute at all, and/or force the human trafficking victim to do things he/she does not want — in a sense, decommoditizing the human body by ignoring the agreed upon value or price. Additionally, traffickers can provide prostitutes as gifts to others with whom they desire to have a familial or business relationship. At the same time, pimps often have no ties with purchasers beyond the transaction and the exchange of the commodities (money for a human body). The trafficker’s “private property” is temporarily transferred to the possession of the purchaser. At the end of the “contract” the possession returns to the pimp. This relationship is understood, meaning that the pimp “gifts” prostitutes to purchasers even though money is exchanged.

Part of the disagreement regarding “sex workers” as autonomous individuals as opposed to sex trafficking victims revolves around economic income. Marissa Fuentes eloquently states, “But focusing on economic prosperity alone obscures the coercive nature of the enterprise of enslaved prostitution.” Furthermore, “economic freedom” and “personal rights” defined by Richard Pipes as “the right freely to use and dispose of one’s assets,” and “the claim of the individual to his life and liberty…in other words, absence of coercion.” Prostitutes, as described, do not have agency over their own bodies, and systems of prostitution do not allow human trafficking victims to practice economic freedom or experience personal rights, preventing these individuals from liberation or empowerment.

In summary, prostitution or “sex work” cannot be liberating as objects cannot be liberated. As a hybrid between a commodity and a gift, the objectified person in question cannot achieve personal or economic freedom. Furthermore, as the opening anecdote shows, many people do not wind up “in the life” on their own ambition but through force, fraud, or coercion. Next time someone says that prostitution is liberation, remember 14 year old Jane Doe and how her life was taken from her, along with her choices.

Kari Carr will graduate with her MA in Anthropology in May of 2018. She has been an intern with ENC Stop Human Trafficking Now and volunteers to promote community awareness of trafficking and to promote anti-trafficking policies and initiatives (https://encstophumantrafficking.org/).