This post is in support of our current exhibit titled Active Measures (Активные Mероприятия). The exhibit is on display on the First Floor of Joyner Library through the end of September. Feel free to contact David Durant (durantd@ecu.edu) with any questions or comments.

A term used to refer to Soviet efforts to influence and manipulate public opinion in other countries during the Cold War, Active Measures has gained a newfound currency in light of the 2016 election influence campaign by Russian intelligence, as well as their overall attempts to shape popular opinion and discourse in the social media environment. This post seeks to put current Russian active measures efforts into a broader historical context.

What are Active Measures?

“Our friends in Moscow call it ‘dezinformatsiya.’ Our enemies in America call it ‘active measures,’ and I, dear friends, call it ‘my favorite pastime.’”

—Col. Rolf Wagenbreth, Director of Department X, East German foreign intelligence (STASI) (Schoen and Lamb, Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications, 8)

According to the authors of a 2017 study, “The term “Active Measures’ came into use in the USSR in the 1950s to describe overt and covert techniques for influencing events and behaviour in foreign countries. Disinformation – the intentional dissemination of false information – is just one of many elements that made up active measures operations.” (Cull, et.al., Soviet Subversion, Disinformation and Propaganda, 6) Other techniques included circulating forged documents, false or misleading news stories (“fake news”), and using agents of influence to shape both public opinion and policymaking.

The Height of Active Measures

During the Cold War, Soviet active measures reached their height during the 1970s and early 1980s. Numerous forgeries and fake news stories were disseminated to influence foreign governments and populations against the United States. Examples include a forged US military document implying American desire to use nuclear weapons on European soil in the event of war; and a forged letter, purportedly from the US Naval Attache in Rome, meant to lend credence to a KGB disinformation story that the US was storing chemical and bacteriological weapons at a base in Naples, Italy.

Most famously, a disinformation campaign begun in 1983 and intensified in 1985 claimed that the AIDS virus had been created in a US biological warfare research facility. Dubbed Operation Denver, the campaign incorporated the efforts of the KGB’s Service A, responsible for active measures efforts, along with their counterparts in the East German Stasi, and other Warsaw Pact secret services.

In a September 7, 1985 message to the Bulgarian intelligence service, the KGB stated that:

We are conducting a series of [active] measures in connection with the appearance in recent years in the USA of a new and dangerous disease, “Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome – AIDS”…, and its subsequent, large-scale spread to other countries, including those in Western Europe. The goal of these measures is to create a favorable opinion for us abroad that this disease is the result of secret experiments with a new type of biological weapon by the secret services of the USA and the Pentagon that spun out of control. (quoted in Selvage and Nehring, Operation “Denver”)

Beginning in 1981, the US government began aggressively pushing back against Soviet active measures efforts, bringing to light and debunking numerous Soviet forgeries and disinformation stories. A special interagency Active Measures Working Group, relying heavily on the State Department and the US Information Agency, was formed for this purpose. It released its first publication, Forgery, Disinformation, Political Operations: Soviet Active Measures, in October 1981. By 1986-87, rebutting the AIDS campaign became a special focus for this body. The Soviets began to back away from the AIDS active measures campaign by late 1987, without abandoning it entirely. They also launched new active measures efforts, such as allegations that Latin American children were being abducted and having their organs harvested for the benefit of wealthy Americans in need of an organ transplant.

The Return of Active Measures

With the end of the Cold War, the concept of active measures seemed to be merely a footnote to history. Under pressure from the United States, the post-Soviet Russian intelligence services abandoned the term “active measures”. However, they remained committed to the general concept, and simply re-dubbed it “support measures.” (Juurvee, The Resurrection of “Active Measures”, 3)

With Vladimir Putin’s return to the Russian presidency in 2012, and the subsequent deterioration of relations between Russia and the West, active measures have reemerged as a key part of the Kremlin’s foreign policy. In particular, the Russian efforts to influence the 2016 American presidential election shows post-Soviet Russia’s continued commitment to active measures, as well as its adaptation of them to the digital age.

As documented in Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s March 2019 report on Russian interference in the 2016 election, the Russians pursued a two-track approach. On the first track, Russia’s military intelligence service, the GRU, began hacking into email accounts of individuals and organizations affiliated with the Democratic Party and Hillary Clinton campaign in March 2016. In July of that year, they used an online cutout to begin sharing the hacked emails with WikiLeaks, who began publishing them later that month. The hacked emails released through WikiLeaks, were, in Mueller’s words, “designed and timed to interfere with the 2016 U.S. presidential election and undermine the Clinton Campaign.” (Mueller, Report on the Investigation, 36)

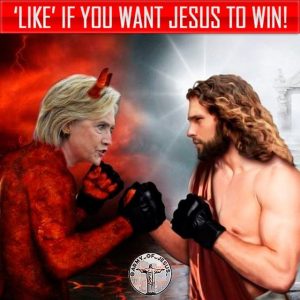

The second track once more involved the spreading of disinformation and “fake news”, in this case through social media via troll and bot accounts. This social media active measures campaign was not conducted directly by the Russian government, but through a private organization called the Internet Research Agency (IRA). Funded by Yevgeniy Prigozhin, a Russian oligarch with close ties to Putin, “The IRA conducted social media operations targeted at large U.S. audiences with the goal of sowing discord in the U.S. political system.” (Mueller, Report on the Investigation, 14) The IRA’s widespread use of fake accounts on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram soon saw it dubbed the “troll farm”. As with the GRU’s efforts, the IRA campaign “favored presidential candidate Donald J. Trump and disparaged presidential candidate Hillary Clinton.” (Mueller, Report on the Investigation, 1)

The Russian campaign to interfere in the 2016 U.S. presidential election shows beyond doubt that active measures have returned with a vengeance.

The Active Measures exhibit is on display through the end of September. The curator thanks Jennifer Daugherty, Larry Houston, Linnea Vegh, and Layne Carpenter, for all their assistance.

Relevant CWIS Blog Posts:

The “Neighbors”: The GRU in America, from “Ales” to “Fancy Bear”

“Putin’s Chef” and the “Troll Farm”: Russian Social Media Subversion in 2016

Recent Revelations About “Fancy Bear”: Russia’s Military Hacking Unit

Exhibit Items:

Forgery, Disinformation, Political Operations: Soviet Active Measures. U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Public Affairs, Office of Public Communication, Editorial Division, 1981. (S 1.129:88)

Image shared on social media in 2016 by Russian Internet Research Agency troll account called “Army of Jesus.” Released by Senator Mark Warner (D-VA), Senate Intelligence Committee, November 1, 2017. Source: Social Media Influence in the 2016 U.S. Elections Exhibits. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, November 1, 2017.

Mueller, Robert S,, III. Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election: Submitted Pursuant to 28 C.F.R. ʹ600.8(c). March 2019. P. 14.

Soviet Active Measures: An Update. U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Public Affairs, Office of Public Communication, Editorial Division, 1982. (S 1.129:101) P. 2-3

Soviet Active Measures: Hearings Before the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, House of Representatives, Ninety-Seventh Congress, Second Session, July 13, 14, 1982. (Y 4.In 8/18:So 8/5) P. 74-75

Soviet Active Measures: September 1983. U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Public Affairs, Office of Public Communication, Editorial Division, 1983. (S 1.129:110) P. 4-5

Soviet Covert Action (The Forgery Offensive): Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Oversight of the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, House of Representatives, Ninety-Sixth Congress, Second Session. 1980. (Y 4.In 8/18:So 8/4) P. 136-137

Soviet Influence Activities: A Report on Active Measures and Propaganda, 1986-87. U.S. Department of State, 1987. (S 1.2:SO 8/12/986-87) P. 79

Soviet Influence Activities: A Report on Active Measures and Propaganda, 1987-1988. U.S. Department of State, 1989. (S 1.2:SO 8/12/987-88) P. 6-7

The U.S.S.R.’s AIDS Disinformation Campaign. U.S. Department of State, 1987. (S 1.126/3:Ac 7)

Usage statistics for the most popular Russian troll accounts on Facebook. Source: Howard, Philip N., Bharath Ganesh, Dimitra Liotsiou, John Kelly & Camille François. “The IRA, Social Media and Political Polarization in the United States, 2012-2018.” Working Paper 2018.2. Oxford, UK: Project on Computational Propaganda. P. 35

Additional Sources:

Boghardt, Thomas. “Operation INFEKTION: Soviet Bloc Intelligence and Its AIDS Disinformation Campaign.” Studies in Intelligence 53 (4), December 2009.

Cull, Nicholas J., Vasily Gatov, Peter Pomerantsev, Anne Applebaum and Alistair Shawcross. “Soviet Subversion, Disinformation and Propaganda: How the West Fought Against it. An Analytic History, with Lessons for the Present: Final Report.” LSE Consulting, October 2017.

Jones, Seth G. Russian Meddling in the United States: The Historical Context of the Mueller Report. CSIS Briefs, Center for Strategic & International Studies, March 27, 2019.

Juurvee, Ivo. Strategic Analysis April 2018: The resurrection of ‘active measures’: Intelligence services as a part of Russia’s influencing toolbox. Hybrid CoE, May 2, 2018.

Schoen, Fletcher and Christopher J. Lamb. Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference. Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press, 2012.

Selvage, Douglas and Christopher Nehring. Operation “Denver”: KGB and Stasi Disinformation regarding AIDS. Sources and Methods Blog, Woodrow Wilson Center, July 22, 2019.