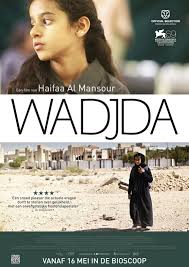

Review of the film, Wadjda, by Haifaa al-Mansour

Lizz Grimsley

Ten-year old Saudi girl, Wadjda, is best friends with a boy, wears blue jeans and sneakers under her abaya, and longs for a bike. She is the subject of strikingly different kind of film about Saudi women, written and directed by Saudi Arabia’s first female filmmaker, Haifaa al-Mansour. This film illustrates the influential role of the media on social institutions and the ways that it can impact how people view the world and think about their cultures.

Saudi Arabia is known for a strict interpretation of Sharia law that oppresses women by denying them the same freedoms and rights as men. As a result, Saudi women have had difficulty breaking out of the restrictive walls built around them. However, Haifaa al-Mansour, shows how the media is capable of challenging oppressive gender roles. It follows the story of a young girl who is interested in purchasing a bicycle that she has seen at a store in her town. Though she is faced with criticism from her family and peers, it does not deter Wadjda from finding ways to save money to purchase the bike. We are also shown an interesting friendship dynamic between her and Abdullah, a young neighbor boy with whom she spends a great amount of time with throughout the movie. As the film progresses, she navigates though her relationships with authority figures in her attempt to understand the world around her. As a result, Wadjda is placed in many situations that alert her to the roles and behaviors traditional Saudi culture views as appropriate for women and girls.

Saudi women have been oppressed by legislation that has denied them the same freedoms and rights as men. This form of systematic oppression has also been responsible for the harsh gender roles and the general mistreatment of women. As a result, Saudi women have little autonomy over themselves or their family units. However, the tides appear to be turning. Windsor reports that In September of 2017, women in the kingdom were finally granted the right drive, and in March of 2018, women who have been divorced were given the right to retain custody of their children without needing to file a lawsuit. But these changes alone are not enough in the fight for equality.

To show audiences the true nature of oppression that exists in Saudi Arabia, al-Mansour uses symbolism throughout the film. One example of this, according to al-Mansour herself, is the bicycle: it is an object that is meant to represent freedom. It is the freedom of adulthood and the freedom of women as separate beings from their male guardians. Thus, Wadjda’s attempts to purchase the bicycle are attempts to gain freedom and control within her own life. By creating an ending where Wadjda owns the bicycle, al-Mansour leaves the audience with a message of hope that things can change for women in Saudi Arabia. Though this is only one interpretation of the film, it has seemed to have a positive impact on the Saudi people. Nikki Baughan quoted al-Mansour in her article, The Reel World, saying “I have a lot of positive feedback from young Saudi women; it means so much to me when they say how much they loved and related to the film.”

As a Saudi woman, al-Mansour had the best knowledge on how to approach the issue of promoting women’s rights. She stated in an interview with Nikki Baughan, “If you try to be confrontational or scream at them about how stupid you think they are, you aren’t going to get through to them. You have to be respectful of the world they come from and present your ideas through that prism.” She said that she wanted her film to reach the average Saudi person, and she knew that she would have to organize her methods in a way that would not deter them. Al-Mansour emphasizes the importance of approaching this social issue with caution instead of as an outsider. Her identity was beneficial in that it allowed Saudi people to trust her and the message she was trying to portray in her film.

Thankfully, her hard work has paid off. Saudi women flocked to watch the film upon its release in 2012 by traveling outside the country. Al-Mansour’s sisters thought the film was “authentic” in the way it depicted the average life in Saudi Arabia. If the goal of the film was to change the perceptions of women and break away from traditional views of women, then Wadjda did just that. As the world inevitably progresses, so do countries like Saudi Arabia. Through social media and educational programs that send their citizens abroad, Saudi people have the opportunity to witness other cultures on a global scale. These interactions will inevitably cause ripples that will disrupt the traditional views imbedded in Saudi cultural practices. Women are being represented in government, legislation is changing, women are being represented in films that point out the flaws of their society. Change may come slowly and with resistance, but with people like al-Mansour advocating for women and girls, their voices are being given a platform that they have never had before.

Lizz Grimsley is a senior at ECU majoring in Sociology and minoring in Anthropology. She plans on graduating in May and has hopes to join the Peace Corps shortly afterwards. She is particularly interested in social issues and understanding how different media sources influence social norms and beliefs surrounding marginalized groups of people.