By Giana Williams

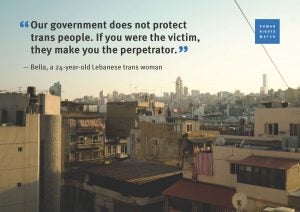

Nancy, a 35-year-old transgender woman living in Beirut, Lebanon, was woken by armed and masked General Security personnel and was arrested and was taken to a detention facility along with other transgender women. She was tortured and was coerced into confessing to fabricated charges of prostitution. She was thrown into an all-male cell, denied medication for her heart condition, access to a lawyer, and was forced to go through HIV testing despite it being illegal under Lebanese law. She was barely given food and water for nearly ten days during her arrest and when she asked to see a doctor, the guards said, “Leave him to rot and die.”

Nancy, a 35-year-old transgender woman living in Beirut, Lebanon, was woken by armed and masked General Security personnel and was arrested and was taken to a detention facility along with other transgender women. She was tortured and was coerced into confessing to fabricated charges of prostitution. She was thrown into an all-male cell, denied medication for her heart condition, access to a lawyer, and was forced to go through HIV testing despite it being illegal under Lebanese law. She was barely given food and water for nearly ten days during her arrest and when she asked to see a doctor, the guards said, “Leave him to rot and die.”

Believe it or not, these situations often happen to transgender individuals in Lebanon. Many are accused of being sex workers because of their appearance and are sent to detention centers without access to a lawyer. They are forced to take HIV tests and if one of them tested positive, the guards would tell everyone in the cell about them and ruin the person’s life by verbally or physically harassing them. Transgenders in Lebanon are often faced with systematic discrimination because of who they are despite how progressive Lebanon is.

Lebanon is one of the few Middle Eastern countries that’s considered progressive when it comes to the recognition of transgender individuals. It’s not illegal to go through sex reassignment and they have the right to change their legal gender once they do. There are often disagreements on sex reassignment surgery in the Middle East from a religious standpoint; is it changing the way the person was created by God or is it to correct his work? Transgender individuals also do not have access to many basic needs such as healthcare, education, a home, a job, and much more. So why are they still being discriminated against even though their country allowed them to be able to legally change their sex and go through reassignment?

Lebanese people value the family as integral to well-being and health as a whole, so it’s not uncommon in their culture to show social support and integration, but the concept of being transgender or part of the LGBT community is not fully accepted. As a result, transgender women often experience threats to their emotional safety due to a lack of support from family, friends, and the community. They are either cut off or shunned from society, causing them to often feel alone and show increased signs of depression and suicidal behavior. It’s unknown if it’s encouraged in Lebanese culture to seek help for mental illnesses or if there is a stigma towards it. Either way, transgender people are often unable to get the help they need because of who they are. The lack of ability to receive health care and other basic needs such as education and home are maybe all possible reasons for the increasing signs of depression and suicidal tendencies for transgender women.

It’s hard to say how we can solve a problem or get more people to accept transgenders in a very religious area like the Middle East. Whenever I hear about the anti-LGBT laws in various Middle Eastern countries, which the majority of their laws are based on their religion, I understand from a religious standpoint but not ethical one. Learning about transgender individuals in the Middle East and the things they go through and the discrimination they face in their country is an upsetting thing to read about. Even though there have been debates on gay and lesbian rights in several Middle East countries, transgender rights are still ignored and those individuals are forced to hide who they truly are to avoid the possibility of being abused physically or verbally.

One thing that could be done is for the area to understand tolerance rather than acceptance. It’s okay to not accept someone’s lifestyle due to your beliefs but being tolerant of their choices and recognizing that they feel more comfortable in the opposite gender is one way to progress in the right direction. By being tolerant of their choices, there will be less of a stigma to being transgender and they will be able to have more access to basic life necessities. Instead of discriminating against transgenders and shunning them from society, people in the Middle East should highlight and recognize not only transgenders but everyone else in the LGBT community and the accomplishments they have made. Having them being more recognized in their society could possibly help broaden their views on people in the LGBT community and have them known as just human beings.

Giana Williams is a sophomore communication and anthropology double major who is set to graduate in May 2022. She currently works for The East Carolinian as the arts and entertainment editor and soon the opinion editor over the summer. Her future plans is to go to graduate school and become a foreign correspondent for Japan.