Courtesy of YouTube, from the 1981 film Reds, Louise Bryant (Diane Keaton) testifies before the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Brewing and Liquor Interests and German and Bolshevik Propaganda, February 20, 1919. The dialogue is substantially derived from the official transcript. (Brewing and Liquor Interests, V. 3, p.465)

When America entered the First World War in April 1917, the country witnessed a major upsurge of nationalistic sentiment, encouraged and often instigated by the federal government. Through a combination of governmental bodies such as the Committee on Public Information (CPI), dubbed America’s “first ministry of information,” and private organizations such as the American Protective League (APL), popular intolerance of anti-war sentiment, and fear of pro-German and radical subversion, reached a fever pitch.

It is thus unsurprising that World War One spawned what historian Alex Goodall has called “the first countersubversive investigative committee in American history,” the forerunner of the House Un-American Activities Committee and the other mid-20th Century congressional committees tasked with rooting out real or alleged subversion. (Goodall, Loyalty and Liberty, 45) A subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by North Carolina’s first popularly-elected senator, briefly immortalized in the 1981 Academy Award winning film Reds, the colorfully named Subcommittee to Investigate Brewing and Liquor Interests and German and Bolshevik Propaganda set the stage for all the countersubversive investigations to come.

The Overman Committee

Fear of German-sponsored subversion was widespread upon the USA’s entry into World War One. While such worries were certainly stoked by the CPI, the popular press, and groups such as the APL, it is important to note that German efforts at espionage, sabotage, and subversion were more than merely the figments of overheated imaginations. In the words of historian Francis MacDonnell:

During the period from 1914-17, the Central Powers mounted repeated acts of intrigue against America. The German and Austrian embassies supervised this clandestine warfare. It included attempts to forge passports, blow up bridges, incite labor unrest, disrupt munitions production, and plant incendiary devices aboard merchant ships. (MacDonnell, Insidious Foes, 11-12)

A particular concern was the brewing industry, dominated as it was by individuals of German descent. In this, wartime fears merged with prohibitionist and anti-immigrant sentiment. A. Mitchell Palmer, the Attorney General, openly denounced the brewing industry as a source of both funding for pro-German subversion as well as moral corruption. In response to Palmer’s accusations, the Senate, in September 1918, passed Resolution 307, which created a subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee tasked with investigating “Brewing and Liquor Interests and German Propaganda.”

The subcommittee consisted of five members. Chairing the group was North Carolina’s Lee Overman. A senator since 1903, Overman made history in 1914 when, in the wake of the passage of the 17th Amendment to the constitution in 1913, he became North Carolina’s first popularly elected senator. Overman was a loyal supporter of President Woodrow Wilson, and strongly opposed to immigration.

The new subcommittee held its first hearing on September 27, 1918, and continued its investigation into early 1919. By the end, the committee had branched out beyond the brewing industry into a broader look at German espionage and subversion. The Overman committee documented a campaign by the Imperial German government to pursue “extensive and far-reaching acts of violence,” directed at the American munitions industry, as well as a widespread effort to fund and disseminate pro-Central Powers propaganda. (Brewing and Liquor Interests, v.1, XIII)

The Overman committee’s work also reflected not only wartime fears, but prevailing concerns about the importance of preserving “Americanism,” and the dangers allegedly posed by large populations of unassimilated immigrants. Its report stated that “a large number” of foreign language publications were “unpatriotic and disloyal to the United States, its principles and institutions.” English-language newspapers that opposed the war were denounced by the committee as encouraging “Germany and German sympathizers.” (Brewing and Liquor Interests, v.1, XXVII)

In terms of the brewing industry, the Overman committee found that they sought to fund, influence, and gain control over numerous politicians, news outlets, and civic organizations. While not directly charged by the subcommittee with aiding the German war effort, the negative publicity the hearings generated for the brewing industry coincided with the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment (Prohibition) in January 1919. In the words of Goodall, “the publicity surrounding Overman’s hearings undoubtedly contributed to the final push for Prohibition.” (Goodall, Loyalty and Liberty, 28)

Turning Attention to Bolshevism

In February 1919, with the defeat of Imperial Germany, and growing fears of radicalism sparked by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, the Senate passed Resolution 436, expanding the mandate of the Overman subcommittee to include the study of Bolshevik-related subversion.

The committee began its hearings into Bolshevism on February 11, 1919. In so doing it became the first congressional committee investigation into communism. In hearings running until March 10, 1919, the Overman committee heard testimony from roughly 25 witnesses. Ironically, in light of the committee’s countersubversive mandate, the bulk of its investigation focused on conditions in Russia and the nature of the Bolshevik regime.

Most witnesses were anti-Bolshevik, but it was the handful of pro-Bolshevik witnesses who provided some of the most memorable testimony. Most notably, on February 20-21, the radical journalist John Reed, and his wife, Louise Bryant, appeared before the Overman committee. The confrontation between the conservative southerner Overman and the radical feminist Bryant was particularly heated at times. Her testimony was marked, as Goodall puts it, by a “deeply gendered hostility” that “produced an almost total impasse between witness and senators.” (Goodall, Loyalty and Liberty, 52)

In its final report, published in July 1919, the Overman committee correctly noted that “only a portion of the so-called radical revolutionary groups and organizations accept in its entirety the doctrine of the Bolsheviki.” The committee nonetheless insisted that domestic radicalism was still a threat:

The radical revolutionary elements in this country and the Bolshevik government of Russia have, therefore, found a common cause in support of which they can unite their forces. They are both fanning the flame of discontent and endeavoring to incite revolution. (Brewing and Liquor Interests, v.1, XLII)

Conclusion

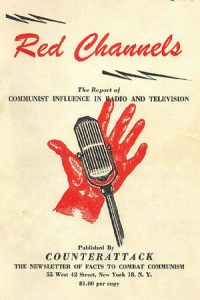

As the first congressional countersubversive committee of the 20th Century, the Overman committee established the precedent that ultimately led to HUAC, the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, and the activities of Senator Joseph McCarthy. It also reflected the trend among countersubversives to tie the threat of foreign or domestic radical subversion to broader social phenomena that they found disturbing, such as fear of further immigration, and worries over unassimilated immigrants. The Overman committee, for example, insisted on “the necessity of Americanizing the residents of this country.” (Brewing and Liquor Interests, v.1, XLVII)

The notion of “Americanism” represented by the Overman committee and its successors remained a potent force in American society until the cultural revolution of the 1960s. When it found itself marginalized in the wake of that revolution, the countersubversive committees it spawned quickly vanished.

CWIS Sources:

Brewing and Liquor Interests and German and Bolshevik Propaganda: Report and Hearings of the Subcommittee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Submitted Pursuant to S. Res. 307 and 439, Sixty-Fifth Congress, Relating to Charges Made Against the United States Brewers’ Association and Allied Interests. 1919, 3v. (Joyner Docs CWIS: Y 4.J 89/2:P 94/4/)

Other Sources:

Goodall, Alex. Loyalty and Liberty: American Countersubversion from World War I to the McCarthy Era. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013. (Joyner Stacks: E743.5 .G63 2013)

Daly, Christopher B. “How Woodrow Wilson’s Propaganda Machine Changed American Journalism.” Smithsonian.com, April 28, 2017.

Eagles, Brenda Marks. “Overman, Lee Slater.” NCpedia.

Inman, Michael. “Spies Among Us: World War I and The American Protective League.” New York Public Library, October 14, 2014.

MacDonnell, Francis. Insidious Foes: The Axis Fifth Column and the American Home Front. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. (Joyner Stacks: E743.5 .M15 1995)

Morgan, Ted. Reds: McCarthyism in Twentieth-Century America. New York: Random House, 2003. (Joyner Stacks: E743.5 .M578 2003)