A fieldwork activity for ECU students includes a study of a maritime cemetery recording and researching grave headstones. In 1813 the Old Burying Ground was erected to contain the bodies of the civilians of Simon’s Town and the sailors aboard the Royal Navy’s Ships, it is now know as the Garden of Remembrance. The Garden of Remembrance is important to Simon’s Town, and to South Africa as a whole because of the history that it contains in regards to the Royal and South African Navy, the development of Simon’s Town as a naval port, and the historical importance of the Kroomen aboard the Naval ships.

Simon’s Town was officially named after the Dutch Governor, Simon van der Stel, who originally assessed the bay and discovered the shelter that it provided in the winter months for maritime seafarers. In 1743, the Dutch East India Company established a working dockyard in Simon’s Town, South Africa. After 50 years of control, the British Royal Navy took over the facility and continued to develop the dockyard and town. Without the presence of the Dutch East India Company’s initial habitation of Simon’s Town, and later on the Royal Navy’s inhabitance, it is very likely that Simon’s Town would have remained a very small backwater town at the end of the Cape Peninsula. The Royal Navy brought prosperity to the town, and it’s shops and taverns. The Dutch East India Company originally chose Simon’s Town because it was a safe haven in the middle of the Cape of Storms. The Netherlands’ Government decided that Simon’s Town was an excellent port to pass men, supplies, and equipment through; simply because it was sheltered off from the stormy, windy weather that was and still is often present in the Cape.

Due to the steep land that surrounds the harbor, the bad weather and incredible swells that give the Cape of Storms its name is blocked off in the small port of Simon’s Town, making it a reliable and safe docking sanctuary for sailors. Although the Dutch East India Company founded Simon’s Town as a dockyard and later on as a safe passage port, the British Royal Navy took control of the harbor in the 1790’s. After the shift of control over to the Royal Navy, they continued to develop the dockyard; eventually, turning it into a Naval Base. The base continued to grow in both practicality and productivity. The Royal Navy issued for the construction of a dry dock, known as the Selborne Graving Dock. This dry dock was of large importance to Simon’s Town’s Royal Naval port; it allowed for the quick and easy repairs to be made to those ships that anchored in said dry dock. Due to the fact that the Cape often had violent storms, many ships were often damaged in this harsh weather, and found that with the help of the dry dock they were easily repaired. Due to the rapid repairs, they were able to continue on their passage through the continuance of the Cape, and the additional storms that they were bound to encounter.

The Royal Navy was prominent, not just for its advancement on the marina, but also for its employment of a particular kind of sailor, one that helped to aid in the growing progression of the Navy. These especial mariners were known as Kroomen, the first black sailors to serve the British Royal Navy. Kroomen were originally from the Kru Tribe, in West Africa. Their homeland assisted in the development of the term “Kroomen”, labeled for their lineage and place of origin. It was very common for ships, in passage through the Cape, to stop at major ports; such as, Freetown, Sierra Leone, to collect their Kroomen. Freetown is coincidentally located on the West Coast of Africa, bordering the country of Liberia, where the Kru tribe was based. These initial black sailors played a cardinal role in the history of the Royal Navy.

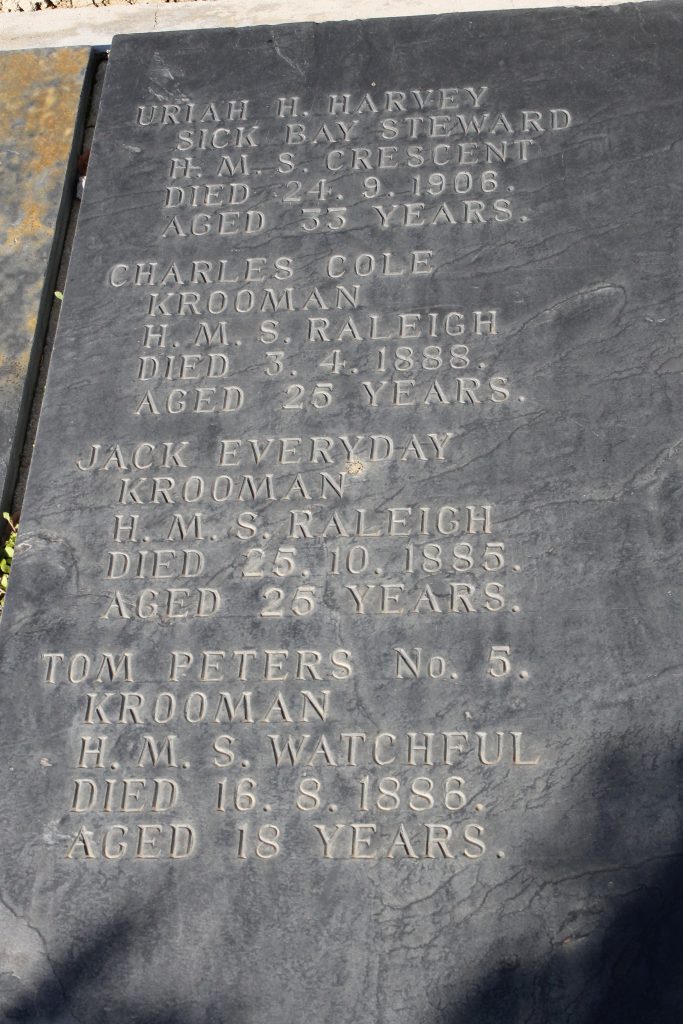

Eighty nine Kroomen are commemorated in the Garden of Remembrance in Seaforth, Simon’s Town. Although these West Africans from Sierra Leone were engaged on British ships since the 1790s, the earliest record of those buried in Simon’s Town was Benjamin Jumbo, head Krooman on HMS Southhampton in 1842. The first employed in the dock yard came from HMS Melville in 1843. The last death commemorated was George Williams on HMS Flora in 1923.

Slavery was abolished in the Cape Colony in 1834. Yet, all enslaved people at the Cape continued to work a four year apprenticeship for their owners, so only technically freed in 1838. Up until 1838, business and the farming sector were in a state of panic as they feared the loss of labour. The Navy had similar labor needs and Kroomen provided an extremely convenient alternative from 1838 to 1935. Many others, only served a three-year work contract at the Cape, then headed home. Others remained in the area, discharged themselves and married local women, or were pensioned off in the community. Their jobs in the Simon’s Town dockyard included mooring ships, clearing coal from lighters, watering ships, coaling ships, and serving as cooks, mates, stewards, carpenters and deck hands on board. They used these skills in port too, as domestic servants and for public services. Outlying services included horse riding companions for the Admiral’s daughters and a local cab business.

Local rules about fraternizing with the False Bay community were largely ignored and the Kroomen, in their jaunty sailor’s outfits of bell-bottoms trousers and tally caps, were very popular, especially with local women. As a result marriages proliferated, further entrenching them in the local community. In a 1898 a Cape Government Commission report the Mayor, Mr. F.H.S. Hugo, described them as excellent servants, well-behaved, non-drinkers and cleanly in their habits. They were the hardest working men he had ever encountered. To stay connected to the Cape colony, they extended their shipboard service contract with the British navy earning certificates, pensions and good service medals. Those that stayed aboard ships or returned to shipboard service also continued to play a role in South African colonial history. For example Lieutenant L.T. Dow of HMS Boadicea served in a naval force for the second Anglo Boer War and received wounds at the battle of Majuba.

The Navy housed the Kroomen in the West dock yard where they were not allowed to leave without permissions. By 1901 the Kroo-town expanded as far as the railway station and tents were erected. There were strict laws about repatriation once contracts expired unless, as on one occasion in 1920, they deserted ship. Five men Palm Tree, Jim Thomas, Bestman, Peasoup, and Sierra Leone were pardoned for their deeds and employed in the Royal Observatory, a step up from the hard labor of the Dock Yard. Amongst West African Kroomen burials are those of a few east African Tindals. Due to political instability in Liberia, plus an expansion of the suppression of slave trade to east Africa in 1870s, replacements on ships were East African Muslims from the coast between Mombasa and Aden known as Seedies. The head of the Seedies unit was termed a Tindal. Although these ships stopped in at the Simon’s Town, most Seedies were discharged into ports of Zanzibar. Prior to World War 1 both Seedies and Krumen served in Naval Brigades around Africa and received campaign medals for Abyssinia 1867-68, Ashantee 1873-4, Zulu 1879, Egypt1882-89, East and West Africa 1889-1900, Queen’s South Africa 1899-1902. They shared a rating system and commanded only amongst themselves. This comprised Kroomen: Head Krooman. Second Head Krooman, and Krooman and a more elaborate system for Seedies: Head Tindal of Seedies, First Tindal, Stoker Tindal, Second Tindal, Second Stoker Tindal, Seedies, Stoker Seedies.

After several years of prosperity and slight expansion the Royal Navy handed over control of the Simon’s Town Naval base to the South African Navy. The port was handed over in 1957, upon the Simon’s Town Agreement. This agreement arranged for the Royal Navy to transfer their control of the Naval base to the South African Navy, and in doing so they relinquished their hold on the port over to the South African Government. South Africa, in exchange, guaranteed the use of the port to the Royal Navy’s ships. This arrangement proved to be mutually beneficial, allowing the British Royal Navy to use the harbor that they worked so diligently on, for many years, to develop; as well as granting the South African Navy the rights to use a well refined inlet, on what was originally South Africa’s endemic territory.