By Mikayla Goode

The sound of an alarm rings as the sun is dressing the sky to signify another day of classes. As you prep and get ready to start the day, a feeling of dread washes over you. “Why must classes be so early?” “I’m tired of school.” These thoughts can run through any university student’s mind on the daily. Let’s picture something for a minute. Imagine finishing fifth grade and never returning school. Sound exciting? This means you can enjoy being home and playing all day, right? When the new school year comes around, you watch as all of your brothers and male friends start middle school while you sit at home tending and helping with all chores. The further you watch your brothers succeed and be praised, the more trapped you feel in your own skin. A couple years go by and as you turn fourteen, and you are married off to a boy of your parent’s choosing to then take care of his home and bear his children, forever suffering from lost opportunities.

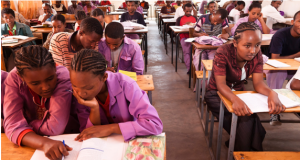

The underlying reality is that education is one of human’s overlooked luxuries. While here in the U.S., we view school as a prison sometimes, we take for granted the hard work and immense payoff education provides us. Currently, with the constant growth of the population, more girls lose the opportunity to receive a thorough education. Sub-Saharan Africa currently holds the largest population of children in general and females in particular out of primary school. In numerous developing countries access to education is limited due to its availability and affordability. Women persuing higher education struggle with the ability to stay safe from the numerous citizens who believe that what they are doing is wrong. Many of these women face discrimination and harassment not only out in public but in their own homes, caused by the deep ideology set in Africa. These attitudes often create an unsafe school environment.

Denying the women of sub-Saharan Africa the opportunity to better their education affects the economy in many ways. An important reason for Africa’s gender bias against the education of women is due to its extreme poverty level. In 2019, seventy percent of the world’s poor lived in Africa; a steady increase from fifty percent in 2014. According to the Institute of Women’s Policy Research, as of 2018, women that worked full-time, year-round made only eighty-two cents for every dollar earned by men, a gender wage gap of eighteen percent.

Why is this important? A large percentage of females living in sub-Saharan Africa suffer from not only the inability to be educated financially, but also from a nation’s outdated ideology. They are discriminated and harassed because of disrespecting the rules place for their gender. While the entire world suffers from the industry monopolized by men, we all as the female gender are suppressed. If the government would support these women and allow access to further their education whether that be primary level to tertiary level, not only will that allow them to succeed and support themselves and their country’s economy, but also aid in the encouragement to prove that women deserve equality in education.

How can we help? Aid for America’s “EFAC: Education for All Children” is a nonprofit organization that provides scholarships based on merit and need for the brightest and most vulnerable youth in Kenya to pursue secondary and post-secondary education. Their message explains that money isn’t the only thing that can help these children to getting an efficient education and rise from extreme poverty. This organization provides an education-to-employment program that will prepare students for careers by developing their leadership and life skills.

To find more information or to donate, please follow the link https://www.aidforafrica.org/member-charities/education-children/

Mikayla Goode is a junior at East Carolina University who is set to graduate May 2021 with a BA degree in psychology and a minor in anthropology. Her future plans are to pursue a graduate degree in counseling and work on helping others struggling under the stigma of mental illness. In her free time, she enjoys reading and journaling.

from a murder charge when she killed the rapist who abducted her. The film brings to light the ongoing issue of child marriage in many parts of the world. This custom of abduction of young girls disrupts their education and chances for a better life, leading to early pregnancies, poor health outcomes and continuing poverty for them and their children.

from a murder charge when she killed the rapist who abducted her. The film brings to light the ongoing issue of child marriage in many parts of the world. This custom of abduction of young girls disrupts their education and chances for a better life, leading to early pregnancies, poor health outcomes and continuing poverty for them and their children.

s among the Masai? What did you like best about it and what did you like least? If you were the film-maker, would you have done anything differently–if so, what and why?

s among the Masai? What did you like best about it and what did you like least? If you were the film-maker, would you have done anything differently–if so, what and why? Leangei Gomez Nuñez

Leangei Gomez Nuñez