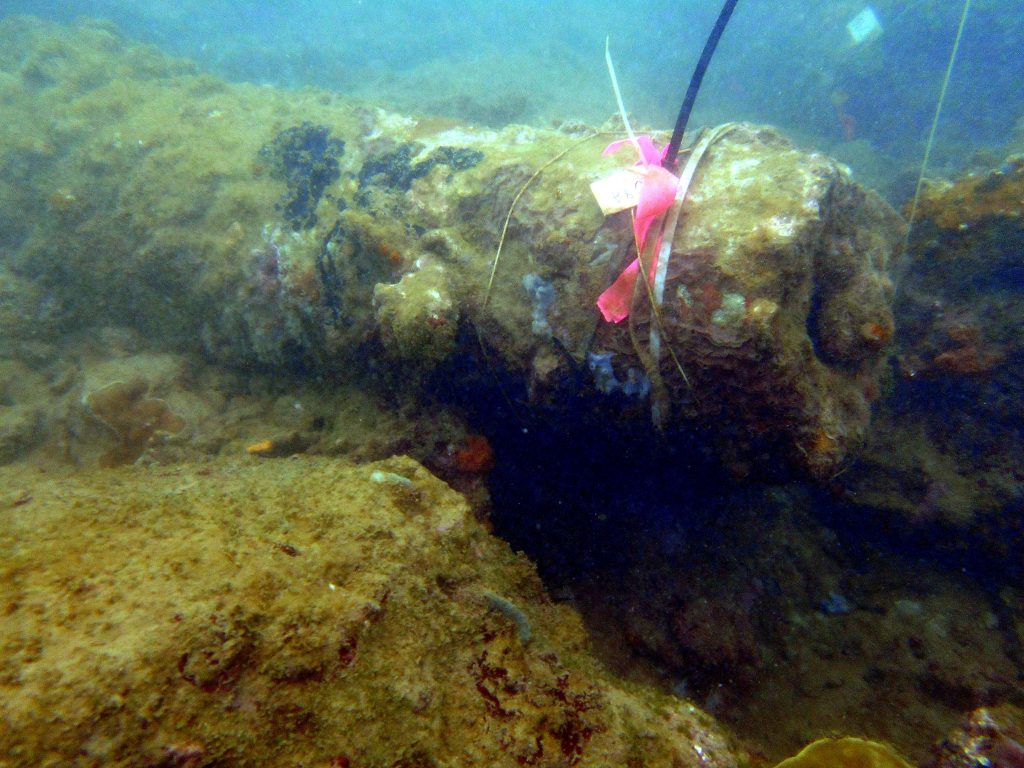

There are only two anchors on site. This one is missing its flukes. The shaft and ring still stand proud on the ocean floor, though.

Some cannon are broken. Others, like this one have artifacts, identifiable and not, concreted to them.

The Cannon site is also home to some impressive corals. Some, like these, have grown overtop of the shipwreck features. Others stand alone, scattered through the site.

To date the two shipwrecks in Cahuita National Park have not been positively identified.

Possible candidates are slave ships belonging to the Danish West Indies Company. The ships are Christianus Quintus and Fredericus Quartus, which are documented to have wrecked in that area in 1710 (Transatlantic Slave Database Voyages 2009; Lohse 2005). These two slave ships and their human cargoes are richly documented in the National Archives of Costa Rica, which is further supplemented by documents from Danish archives. Primary sources provide details of the ships’ voyage on the African coast, the Middle Passage, and discharge of Africans into the Costa Rican community.

Fredericus Quartus took on 11 slaves when it stopped for provisions at Cape Three Points (Cabo Três Pontas) on the western Gold Coast and 323 slaves at Denmark’s main trading station at Christiansborg, near Accra. On 15 September, some of the captives revolted aboard the ship while it was anchored off the Slave Coast; the crew killed the alleged leader and tortured an unspecified number of rebels as an example to the others before the Fredericus Quartus sailed for the St. Thomas in the Caribbean. The Christianus Quintus obtained the whole of its cargo on the Slave Coast in the Bight of Benin. During the voyage to St. Thomas disease and starvation claimed the lives of 135 Africans on board Christianus Quintus V and Fredericus Quartus IV. The ships were more than 1200 nautical miles off course to their planned destination, finally landing at ‘Punta Carreto’ (modern day Cahuita), on 2 March 1710. Captain Diedrich Pfieff wanted to head to Panama, but provisions on board were almost completely exhausted, so the crew sent 650 African slaves ashore and then mutinied, breaking open the ship’s chests of trade goods to secure provisions for themselves.

They proceeded to burn Fredericus and allowed Christianus to run aground in the surf. According to information later supplied by the Danes, most Africans escaped into the coastal forest bush. Reports suggest they were assimilated by the Miskito Indians or absorbed into the local community as slaves. According to oral history, Costa Rican colonists captured 24 of the Africans, who claimed to be culturally affiliated to peoples from the Slave and Gold Coast (Lohse 2005b:135).

Interest in the archaeological project and shipwreck site in the waters off Cahuita Point began with a preliminary site assessment by archaeologist Steven Gluckman in 1978 (now deceased). His site report depicted a map of cannon and a brick area with evidence of manilas or slave trade bracelets (Gluckman 1998:453-468). In June 2012, maritime archaeologists Lynn Harris (East Carolina University) and David VanZandt (Cleveland Underwater Explorers) visited the site. The results of the fieldwork suggest that there are 2 anchors, at least 10 cannon on a reef – representing one site – and a cargo/ballast area, containing brick ballast and 2 cannon located closer to shore that may represent part of the original site or a second shipwreck. Another Park Service report stated that they found “cannon, cannon balls, cooper or bronze manacles, or armbands, used in slave trade, a grindstone under the bricks, and another wooden object also under bricks, several swords, a glass, two plummet stones, a barrel, a glass, and a piece of a bottle” (Boza and Mendoza 1981: 279-280).

Slave ship archaeological investigations currently have high research priority within the discipline of maritime archaeology. Thematically, these sites represent a neglected aspect of scholarship that includes shipwrecks like Meermin, Henrietta Marie, Fredensborg, and Adelaide.

Anchor Recording

One of the sites we will investigate is known to have numerous cannon and at least two anchors. There is an alleged third anchor associated with the second shipwreck site, too. Anchors can help identify a shipwreck’s time period, origin, and purpose because they have diagnostic and stylized features that have undergone a visible evolution through time. When an anchor is present on site, typologies can assist archaeologists in identification and interpretation.

The Cahuita shipwreck sites are thought to be from the eighteenth century – clues from the anchors will help to determine if this is an appropriate date range. Anchor style was evolving at this time. Arms were becoming more curved and there were several stock shapes including straight, upturned, and concave. These can be identifying characteristics. Different countries were using a variety of anchor designs based on the styles perceived strengths. Similar to cannon, though, a broken anchor would have been replaced at the next possible port. Thus, one ship could have a variety of anchors in different styles. This means that even precise identification of an anchor cannot positively define a shipwreck’s age and origin; instead, archaeologists gather a variety of data to interpret a wreck site.

The Cahuita project will use the Nautical Archaeology Society’s (NAS) Big Anchor Project proforma and recording guidelines. Challenges include the proforma’s restrictions and potential missing features on the anchors. The Big Anchor Project generally records “decorative” anchors – samples found outside of historic sites, museums, and ports that are not commonly concreted or broken like the anchors found on the Cahuita shipwrecks. Concretion layers will make it difficult to record the shapes, sizes, and details. Almost all anchors from this time period also had wooden stocks. These have likely deteriorated over time. Features associated with wooden stock may be present, but will require additional identification and interpretation.