By Alexis Bullin

Trigger Warning: This contains discussion including sexual violence, abuse, warfare, and death.

“I was thirteen when the war spread to my city. I was kidnapped by four sol

diers who locked me in a house where I was raped every day by

different men for eight months. I had a miscarriage while I was there. When the war ended, soldiers wearing unfamiliar uniforms came and told me to go home, but my city had been destroyed and

my family was dead. I moved to Sweden with a man I trusted, and he sold me to a pimp in Stockholm. Later the police sent me back to my country, but I am still afraid to go outside, because I worry that everyone can tell what happened just by looking at me”. The encounter above is told by Suada, a woman from Bosnia-Herzegovina. This encounter is similar for many women and children globally. Manipulation and violation perpe

tuated through war is a growing threat. The instability of war leads to the victimization of women and children in the wake of warfare perpetuating the manipulation of women and children through sexual assault/violence, forced militar

y recruitment, human trafficking and displacement.

Women are often the victims of violence during warfare. They can be killed or maimed but they also suffer sexual violence through war rape. Many times, soldiers view rape as a way to terrorize and humiliate the male members of enemy groups. But women bear the consequences which can include pregnancies and psychological trauma. Women and children are also used for forcible impregnation causing them to bear their rapists’ children. The US labels this a form of implicit genocide, where the rapists take over the bodies of their victims and act to exterminate the indigenous population.

forced pregnancy – a tactic that has been recorded historically and used by Genghis Khan. Forced pregnancy is a form of enacting genocide or slavery. These various attacks and violations against women and children are used as an extension of the battlefield.

In addition, women and children are often forced into serving the military goals of the enemy as forced soldiers or terrorist instruments. Attacks such as these have been seen during the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Women and children are forcibly recruited and used to facilitate armed conflict and terrorist attacks. This is a direct violation of human right as well as the murder of millions of women and children. Forced soldiers lose their rights to healthcare, education, and autonomy; working against their will, wounding themselves and others.

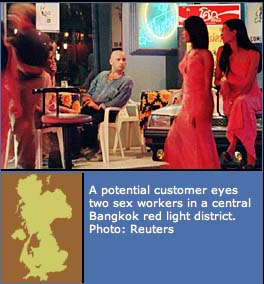

The political and economic instability of war creates the conditions leading to increased labor and sexual trafficking of women and children. Human trafficking is a global threat, however, areas that are riddled with warfare are subject to exponential spikes in activity. Many women and children are sold or forced into the sex trade. This trade sustains the sexual and mental abuse of women and children. In many places, prostitution is considered illegal and punishable, however, human trafficking is widely tolerated by governmental officials and police. This is true for many areas post-war.

Finally, women and children, are often displaced from their homes and livelihoods after war and bear a disproportionate burden of trying to find sustenance and support for their families. Poverty and displacement effects women and children at a disproportional rate. With the destruction of property, women and children often fall into the direct disadvantage of displacement and poverty. This is often the result of little to no governmental or monetary protection provided to women and children. Women’s responsibilities following war are formidable, considering women are expected to be peacemakers that maintain order on a familial and communal level. Often underrepresented, women and children find themselves excluded from governmental protection. This omittance of protection amplifies the stress and trauma that women and children face in the wake of warfare.

Women and children face adversity daily; however, these adverse circumstances are amplified in the face of war. Using women and children as an extension of the battlefield, whether through sexual violence, forced labor/recruitment, human trafficking or displacement is malice in its deepest form. For too long women and children have been the scape goats for violence and extremism, therefore something has to change. March Twelfth of this year the United Nations met to discuss the threat associated with war that women and children face. Within the next year, they plan to allocate and demand legislation that will protect women and children from the catastrophe and trauma of war. “To the best of my knowledge, no war was ever started by a woman. But it is women and children who have always suffered most in situations of conflict” – Aung Sun Suu Kyi.

Alexis Bullin is a Senior at East Carolina University. Graduating with a Bachelor of the arts in Anthropology, Alexis’ main interests are Middle/Near Eastern Ethno-Archaeology, the cross-cultural treatment of women, and the effects of warfare. In her free time, she loves gardening and songwriting.

Equality Ministries launched a public campaign program to raise awareness regarding sexual harassment. But would this effort be enough to change things? And why did it take so long to happen?

Equality Ministries launched a public campaign program to raise awareness regarding sexual harassment. But would this effort be enough to change things? And why did it take so long to happen?

e left them incontinent and shunned by their husbands and the communities in which they live. Why is obstetric fistula known as the silent epidemic and why does it disproportionately effect women in the developing world? Why do some of the women in this film say that death would be preferable to living with fistula? If you were tasked with doing something to help prevent this problem in countries like Ethiopia, what would you do–where would you begin and why?

e left them incontinent and shunned by their husbands and the communities in which they live. Why is obstetric fistula known as the silent epidemic and why does it disproportionately effect women in the developing world? Why do some of the women in this film say that death would be preferable to living with fistula? If you were tasked with doing something to help prevent this problem in countries like Ethiopia, what would you do–where would you begin and why? from a murder charge when she killed the rapist who abducted her. The film brings to light the ongoing issue of child marriage in many parts of the world. This custom of abduction of young girls disrupts their education and chances for a better life, leading to early pregnancies, poor health outcomes and continuing poverty for them and their children.

from a murder charge when she killed the rapist who abducted her. The film brings to light the ongoing issue of child marriage in many parts of the world. This custom of abduction of young girls disrupts their education and chances for a better life, leading to early pregnancies, poor health outcomes and continuing poverty for them and their children.

s among the Masai? What did you like best about it and what did you like least? If you were the film-maker, would you have done anything differently–if so, what and why?

s among the Masai? What did you like best about it and what did you like least? If you were the film-maker, would you have done anything differently–if so, what and why? Femicide is defined as a sex-based hate crime, “the intentional killing of females because they are females” Every year, about 66,000 women are killed violently across the globe. Mexico has been experiencing a crisis of femicides. The rate has more than doubled with 3580 women being killed in 2018. Fresh outrage has been sparked in Mexico by the brutal murder this month of Ingrid Escamilla, 25, who was found stabbed to death and partially skinned and by the disappearance of 7-year old Fátima Cecilia Aldrighett Antón on Feb. 11 in the Mexico City neighborhood of Xochimilco, where she was waiting to be picked up from school. Four days later, her body was found naked in a plastic bag. These crimes sparked a wave of protests in Mexico City, and feminists have accused President Andrés Manuel López Obrador of brushing them off. The Washington Post reports that in the midst of a fundraising campaign linked to the sale of the presidential plane, Obrador chastised a reporter who asked him about the attacks on women: “I don’t want femicides to distract from the raffle.” Last week protestors painted “femicide state” on the walls of the national palace. They accuse authorities of doing nothing to investigate or punish the perpetrators of violence against women. In Mexico’s National Congress, the opposition National Action Party proposed creating a special committee for femicides, claiming a “state of national emergency.” Josefina Vázquez Mota, president of the Senate Committee on Children and Adolescents, said data from Mexico’s Children’s Rights Network shows seven girls and boys disappear in the country every day. Police have also been implicated in recent crimes of rape against women. Mexico’s city first female mayor is urging action. Latin America has some of the world’s highest rates of femicide in part because gang violence is so high overall. But yet these same countries have declarations against femicide on the books but do not enforce them. Some say the issue lies with how the term is defined. In Chile and Nicaragua, a crime is not femicide if the perpetrator did not know the victim. Mexico does not define femicide, allowing many murders to go unclassified, making it difficult to gather reliable statistical data on rates of gender violence. Honduras and El Salvador have the highest murder rates for women in the world, and a key reason is the control by drug traffickers of much of the country. Patriarchal values that view rape and interpartner violence as justified or that favor the rights of men to control women also make enforcement of laws difficult.

Femicide is defined as a sex-based hate crime, “the intentional killing of females because they are females” Every year, about 66,000 women are killed violently across the globe. Mexico has been experiencing a crisis of femicides. The rate has more than doubled with 3580 women being killed in 2018. Fresh outrage has been sparked in Mexico by the brutal murder this month of Ingrid Escamilla, 25, who was found stabbed to death and partially skinned and by the disappearance of 7-year old Fátima Cecilia Aldrighett Antón on Feb. 11 in the Mexico City neighborhood of Xochimilco, where she was waiting to be picked up from school. Four days later, her body was found naked in a plastic bag. These crimes sparked a wave of protests in Mexico City, and feminists have accused President Andrés Manuel López Obrador of brushing them off. The Washington Post reports that in the midst of a fundraising campaign linked to the sale of the presidential plane, Obrador chastised a reporter who asked him about the attacks on women: “I don’t want femicides to distract from the raffle.” Last week protestors painted “femicide state” on the walls of the national palace. They accuse authorities of doing nothing to investigate or punish the perpetrators of violence against women. In Mexico’s National Congress, the opposition National Action Party proposed creating a special committee for femicides, claiming a “state of national emergency.” Josefina Vázquez Mota, president of the Senate Committee on Children and Adolescents, said data from Mexico’s Children’s Rights Network shows seven girls and boys disappear in the country every day. Police have also been implicated in recent crimes of rape against women. Mexico’s city first female mayor is urging action. Latin America has some of the world’s highest rates of femicide in part because gang violence is so high overall. But yet these same countries have declarations against femicide on the books but do not enforce them. Some say the issue lies with how the term is defined. In Chile and Nicaragua, a crime is not femicide if the perpetrator did not know the victim. Mexico does not define femicide, allowing many murders to go unclassified, making it difficult to gather reliable statistical data on rates of gender violence. Honduras and El Salvador have the highest murder rates for women in the world, and a key reason is the control by drug traffickers of much of the country. Patriarchal values that view rape and interpartner violence as justified or that favor the rights of men to control women also make enforcement of laws difficult.