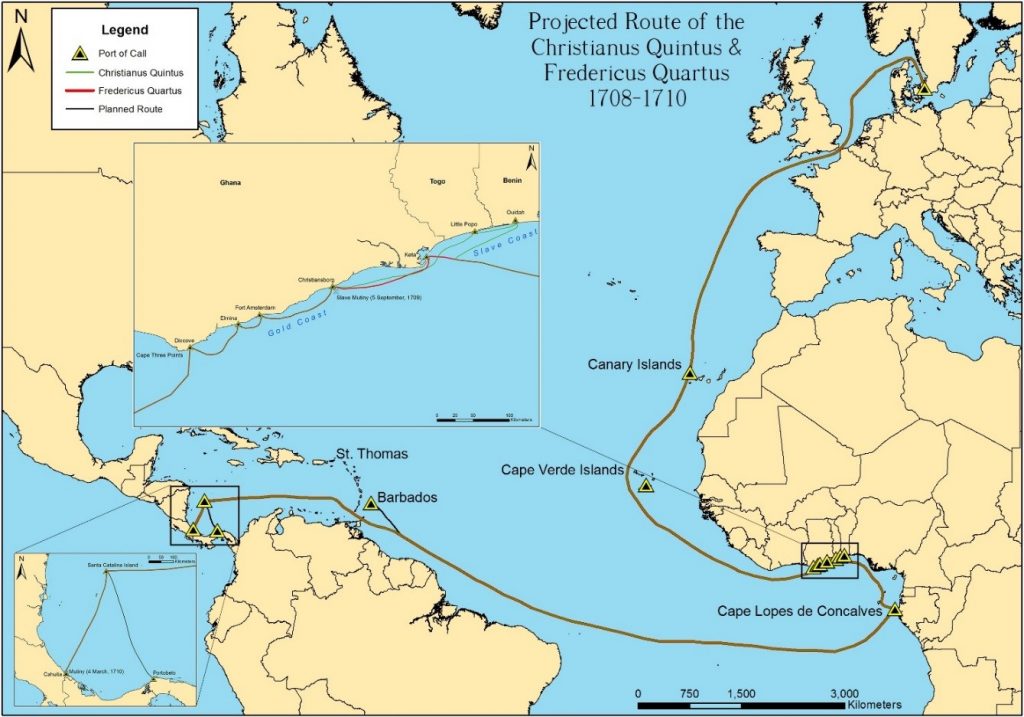

In 1708, Christianus Quintus and Fredericus Quartus commenced their final voyage for the Danish West Indies Company. Both vessels sailed from Copenhagen in December of that year armed with 24 cannon and a crew of 60 (Holm 1978:183). After loading 450 men, women and children as slaves and thousands of tons of elephant ivory, the vessels departed for St. Thomas. Fearing rebellions, the captains of the two slave ships sailed close together throughout the voyage, but due to navigation errors missed Barbados by three degrees to the north. The crew were confused about location and concerned about the small quantity of remaining food. Upon arrival in the Caribbean, they landed on St. Catalina Island, 300 miles away from St. Thomas, their original destination. After realizing their navigational errors and accepting that they could not return to St. Thomas given their lack of supplies, the captains decided to proceed to Portobelo, Panama in an attempt to sell their remaining slaves and to acquire supplies (Holm 1978:184-185; Justesen 2005:231; Lohse 2005: 147).

When the two ships approached land, the crew encountered a heavy storm forcing an unanticipated landing 500 miles away on a shoreline that they believed to be Punto Caretto in Nicaragua (Norregaard 1948: 81). Holm (1978: 185) suggests that the name of the point or peninsula was misinterpreted and rather corresponds with the location of Punta Cahuita, Costa Rica. Jamaican fishermen piloted the captains to a bay where the ships anchored.

The anxious crew confronted Captain Pfieff and demanded slaves be released so the rest of the food could be divided amongst them. When the captain denied their request, as well as their subsequent demand for a month’s pay, the discontents threatened mutiny. In an attempt to appease the sailors, Pfieff decided to release the slaves ashore, but the at this point the crew were no longer satisfied with the captain’s concessions. They broke open chests and divided the ships’ gold among themselves, thereafter setting Fredericus Quartus alight using a pile of refuse, tar and pitch. The boatswain of Christianus Quintus deposited the crew ashore and cut the anchor cable, allowing the vessel to break up in the surf. The crew hired a group of Jamaicans to transport them to Panama. Left with no other option, the captains returned to Denmark (Holm 1978:186).

When the crews of each vessel mutinied upon arrival at Punta Cahuita, one vessel was burned to the waterline and left to the elements. Initial research into the historical record for these vessels revealed that Christianus Quintus contained an outbound cargo intended for Africa such as cloth, metal goods, and weapons all to be traded with the Africans, as well as building materials, bricks, and boards to repair and enlarge Danish forts on the African coast (Nørregård 1948:70). The initial cargo of Fredericus Quartus included 30 chests of sheets, eight chests of guns, two casks of knives, 522 bars of Norwegian iron, 648 bars of Swedish iron, and nineteen cases of gifts to sell and trade in Africa (Holm 1978:183). Leftover African trade cargo often remained in the holds of vessels and was intended for further lucrative trade in the Caribbean. Both of these slave ships were bound for St. Thomas, a Danish port in the West Indies at the time. During this time, northern European building traditions heavily utilized brick, and this style of construction dominated the built heritage exhibited in the Danish West Indies.

Another possibility for the site is that the bricks represent an individual vessel with solely a cargo of bricks, bound for Costa Rica. In this instance, the yellow brick that is found on the brick site may in actuality be a type of clay brick that originated in Spain. Spanish colonial architecture made use of a variety of bricks and this style of construction was common in Central America during the suggested time period. Local fishermen often describe these shipwrecks as Spanish galleons that wrecked off the coast. This is also a strong possibility and requires further historical research into Spanish trade with the Miskito indigenous population in Cahuita (Borrelli and Harris 2017).