Site Name/Number:

Portsmouth Island Life Saving Station. LCS Number: 012512

Location (Description and Coordinates):

35⁰ 4’ 6.535”N, 76⁰ 3’ 27.424”W. WGS 1984. GPS coordinates correspond with the front door of the station. Located on the eastern portion of the Portsmouth Village Historic District on Portsmouth Island. Situated along Coast Guard Creek.

Date Dived/Inspected:

East Carolina University’s Maritime Studies Program inspected the Life Saving Station on June 3, 2019 during their Summer Field School.

Weather on date of Inspection (tide, etc.):

High of 80℉. Average wind, 7.8 mph NE, highest 16 mph NE. Measurements taken from Cape Hatteras according to National Weather Service Station in Morehead City, North Carolina. Moderate to complete cloud coverage throughout the day.

Depth:

Terrestrial site. Potentially remnants of wharf structures in Coast Guard Creek. Approximately 2-3 ft. of water.

Visibility/Current:

Terrestrial site. Within Coast Guard Creek, visibility fluctuates according to tides, wind direction, and level of activity taking place.

Environment (general and biological):

The environment of Portsmouth Island is a mixture of grassland, thick shrub savannahs, salt marshes, and shrub thickets. Portsmouth Island is also a tidal island heavily influenced by incoming and outgoing saltwater. Around the Life Saving Station, vegetation consists of shrub savannah and grassland. The Park Service and volunteers maintain the grounds and keep the grassland from growing excessively. Behind the station going towards Coast Guard Creek and Ocracoke Inlet is an expansive tidal marsh (National Park Service 2007).

Bottom Composition (sediment description, slope, topography, etc.):

Portsmouth Island is a generally flat landscape, with areas of slight elevation throughout called hammocks. Buildings, cemeteries, and other cultural resources are built on top of these hammocks to minimize damage incurred through tidal effects and flooding. The area around the Life Saving Station is flat, with a section being used as an airstrip during the 1940s. Besides sand, soil sediment on Portsmouth Island is either Lafitte-Hobucken-Carteret, associated with areas frequently flooded by salt water, or Newhan-Corolla Beaches soil, a permeable, sandy mixture. Coast Guard Creek is an extremely mucky, silty sediment (National Park Service 2007).

Brief Historical Context:

Construction of the Portsmouth Island Life Saving Station was finished in June 28, 1894, six years after Congress authorized the construction of one on the island. Similar in design to approximately twenty other stations built in the 1890’s, specifically one located at Quonochontaug in Rhode Island, the Portsmouth Island Station became the largest building on the island. The Life Saving Station provided a valuable safety net to shipping traversing through or around the treacherous Ocracoke Inlet. The most notable rescue took place in 1903 when the barkentine Vera Cruz ran aground on Dry Shoal Point. The crew performed thirty-two separate trips in the boat to rescue approximately 400 passengers from the stranded ship. After the merging of the Life Saving Service and Revenue Cutter Service into the United States Coast Guard, the station became a Coast Guard Station and its occupants took on additional responsibilities. The passage of the Eighteenth Amendment made the smuggling of alcohol the station’s primary concern until its repeal in 1933. Ultimately, the repeal of the amendment led to the decline and eventual deactivation of several Coast Guard stations, including Portsmouth in 1938. It reopened again after the attack on Pearl Harbor in order to provide coastal observation during World War II. Permanently closed after the end of the war in 1946, the station briefly served as a private club house for the Brant Rock Rod and Gun Club before being incorporated into the Cape Lookout National Seashore in 1977. The station and its grounds are currently on the National Register of Historic Places as of November 29, 1978 (Jones 2006).

Along with the Life-Saving Station house, there are several outbuildings on the property. The oil house was built in 1894 and after years of destruction from storms, finally removed before or during the early 1940s. The station privy, outhouse, was built in 1910 and originally located along the seawall. It was removed in 1940s after decades of damage from storms. A stable for horses was built in August 1896. It was destroyed in a hurricane in 1899, but replaced immediately. Eventually, new stables were constructed in 1910 and again in 1928. Currently these are used as a garage and storage building for National Park Service equipment. In 1897, a boat house was constructed on the beach to house the shore boat used in rescue operations. It was damaged by hurricane in 1899 and eventually condemned in 1905. The crew salvaged the building and moved it back to the station yard and used as storage for the shore boat. The station erected a wreck pole in early 1895. Wooden breakwaters were built in 1896, as well as a dam at the head of Coast Guard Creek. The wooden structures were frequently damaged by storms and needed to be replaced by concrete bulkheads and seawall in 1914. Due to funding issues, these structures were not completed until early 1918. Wooden walkways throughout the ground were removed during summer of 1915 and replaced with concrete walkways. In addition, concrete ramps to the boat room were completed by that fall. During the station’s reopening during WWII, the oil house and other outbuildings were removed (Jones 2006).

Methods of Investigation:

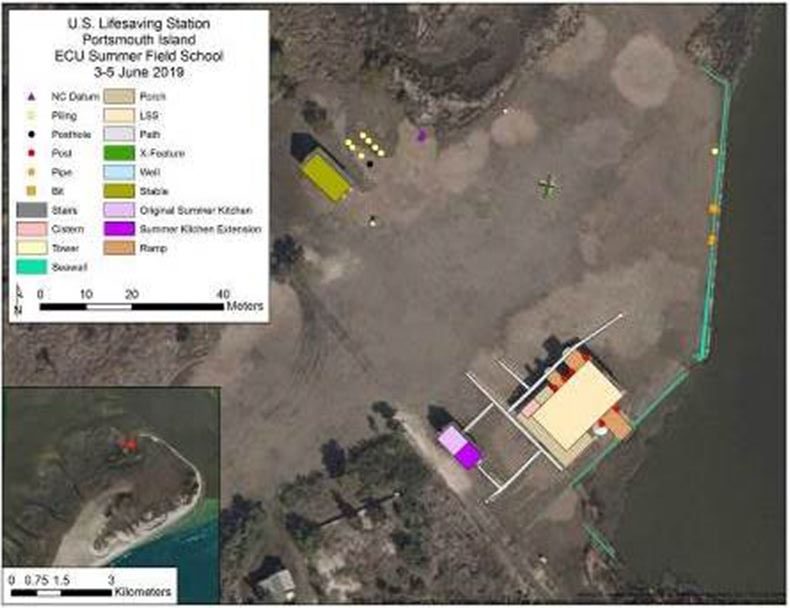

Project team performed an exterior and interior survey and recording of the Life-Saving Station. The exterior team used a RTK, Real Time Kinematic, positioning system to plot the surviving structures and station grounds. This system uses a base station and a rover station connecting to satellites in order to give positions accurate to within centimeters. The team aimed to maintain a fixed reading from the base station and stay locked to at least 20 satellites in order to maintain this level of accuracy. After establishing the base station in an open, flat location, the team used the rover station and a Windows tablet to record the corners of the buildings, walkways, and other identified features. These positions were inputted into ArcMap to demonstrate the current extent of structures on the grounds. These can also demonstrate, when combined with historical maps, the evolution of the Life Saving Station and how it has been altered recently. The interior survey recorded the dimensions of architectural features such as the windows, mess room, fireplace molding, and stairwell. These measurements were taken with a 30 meter tape and recorded in team members’ field notebooks. Specific attention was paid to the boat room and second floor crews’ quarters. Additionally, measurements were taken using 30 meter tape measure and seamstress tape from the Pigott Skiff which is housed within the Life Saving Station and recorded into field notebooks. Team members used these measurements to create first a hand drawn scale plan view of the vessel which was ultimately converted into a digitized scale drawing using Microsoft PowerPoint.

General Description (of site):

The site is situated in the eastern portion of the historic village, adjacent to Coast Guard Creek along a SW to NE axis. The dominant feature is the Life-Saving Station which contains seven rooms and an observation area on the third floor. The entranceway to the station is surrounded by a porch which also contains a brick cistern on the western side as well as a wooden one on the opposite side. The eastern cistern was originally constructed out of metal, but it was dismantled in 2000. The summer kitchen is directly in front of the station, with evidence of its extension before World War II visible along the foundation of the structure (Jones 2006). The earlier, smaller kitchen has a solid concrete foundation while the addition was built on wooden pilings. To the west, the stable stands next to the foundational pilings of another building, potentially the boat house. Additionally, a depressed part of the land next to the stables possibly indicates the historical footprint of another building. The seawall still remains along Coast Guard Creek and the boat ramp from the station, as well as two ramps on the opposite side. There is evidence of a concrete tower to the northeast of the stable, but more research is needed to confirm.

The concrete pathways are still present on site, with evidence of alteration and change of direction. No evidence of the wreck pole or coastal warning display tower were located. A fence post is in the marsh at the northeastern edge of the site, possibly the location of the property’s perimeter fence.

Features (Natural and Cultural):

Portsmouth Island’s Life-Saving Station is located along Coast Guard Creek, a small creek providing access to Ocracoke Inlet from the station. The seawall has prevented erosion of the ground and small flooding during storms. Flat terrain which was used to accommodate a landing strip during the station’s use as a hunting lodge. A road runs directly in front of the Life Saving Station providing access to Haulover Point to the west and the beach to the east. NC Geodetic survey markers located to the northeast of the stables. Signs partially obscured by marsh. In addition, there are interpretation signs scattered throughout the grounds along the path leading towards the beach, the Life-Saving Station, and one located outside a storage facility to the southwest of the station.

Artifacts:

Artifacts within the Life-Saving Station include replicas of the Lyle Gun, the shot line and flaking box, a breeches buoy, a beach cart, and the Monomoy surfboat. All artifacts were used in shoreline rescues. Also, Henry and Lizzie Pigott’s skiff is housed within the station, an artifact related to the Historic Village of Portsmouth. Outside of the station house, an iron pipe is located along the seawall. It is unclear whether or not this is associated with the station.

Human or Environmental Impacts:

Since permanent inhabitants have left the island, brush has grown significantly in areas not maintained by park staff. This, in conjunction with being a tidal island, fosters a significant mosquito and greenhead fly population. Salt water and exposure have already began to erode portions of the seawall and ramps at the Life-Saving Station. Wood shingles were replaced in 1978 and the screen was removed from the porch (Jones 2006).

Potential Threats:

Storms possess a major threat to the surviving structures of the Life-Saving Station. Severe wind and flooding can destroy or erode portions of the seawall and remaining structures. Structures are not built on tall stilts or foundations, severe rainfall and winds could drastically damage site. Hurricane Isabel flooded the station with 22” of water, severely damaging the eastern wall and boat room floor (Jones 2006). Unattended tourists can damage and alter the station’s grounds in a variety of ways. The deterioration of the seawalls and ramps exposes their construction method, a concrete mixture of sand and shells, which could be tempting to remove. Since most of the structures are constructed from wood, termite damage and other long-term exposure damage is possible. The National Park Service and volunteers have maintained and repaired the property after several flooding incidents.

Associated Artifacts Onshore or Nearby (i.e. museums, private collections):

Plot plans are housed in the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, RG26. Station Log Books from 1894-1938 are housed in the National Archives at Atlanta, RG26.4. Surviving structures from the station and Portsmouth Island may have been relocated to Belhaven, NC according to a personal testimony from Jeffrey West, NPS Superintendent for North Carolina’s Cape Lookout National Seashore.

Associated References:

Jones, Tommy H.

2006 Cape Lookout National Seashore Portsmouth Life-Saving Station Historic Structure Report. National Park Service, Southeast Regional Office, Cultural Resource Division, Historical Architecture. Atlanta, GA.

National Park Service

2007 Portsmouth Village Cultural Landscape Report. National Park Service, Southeast Regional Office, Cultural Resources Division. Atlanta, GA.

Noble, Dennis L.

1994 That Others Might Live: The U.S. Life-Saving Service, 1878-1915. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD.

Shanks, Ralph and Wick York

1996 The U.S. Life-Saving Service: heroes, rescues, and architecture of the early Coast Guard. Lisa Woo Shanks, editor, Costaño Books, Petaluma, CA.

Future Research Potential:

Further research into the specifics of Portsmouth’s Life-Saving Station is needed. Most of the information, in the NPS report and on site, are inferred from other stations constructed around the same time. Perhaps, a more in-depth social history of those inhabiting the station or how Portsmouth residents reacted to the construction and expansion of the station. The relocation of additional structures can build upon the site map created by the positions obtained from the RTK system.

Future Public Outreach Potential:

Station already opened and converted into a museum. Showcases daily life and evolution of Portsmouth Island Life-Saving Station. Summer kitchen and stable could be opened and converted in the same manner, further documenting daily life for Portsmouth’s station keepers. Additionally, demonstrations of the Lyle Gun and other saving apparatuses would reveal the difficulty of these life-saving methods.