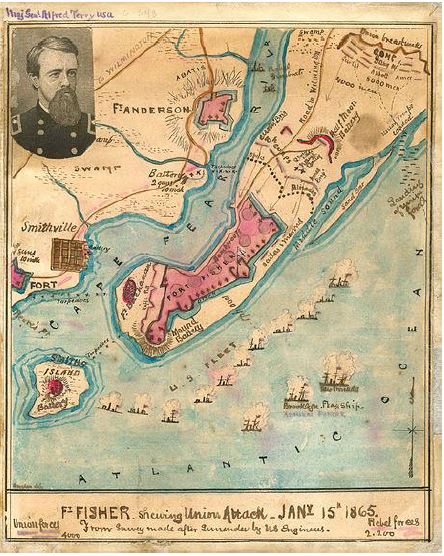

The Fort Fisher Historic Civil War site is located 18 miles south of Wilmington on U.S. 421. It is National Register Number: 66000595 defense – fortification. It was classified as threatened in 2008. Current use is a state park. Today, its significance is as an earthen Confederate stronghold which created an impassable barrier for the blockading Union fleet. Its fall, in January 1865, helped spell the collapse of the Confederacy. The earthen fortifications of Fort Fisher have suffered due proximity to the Atlantic shoreline. Beachfront erosion destroyed most of the fort by the 1950s. Fortunately, this tidal erosion was arrested in 1996 with installation of a stone revetment wall. However, the erosion caused by wind and rain continues to damage the remaining earthworks. The ground cover is inadequate for preservation, and past maintenance practices emphasizing curb appeal have been detrimental. Without appropriate ground cover and a proper maintenance plan, erosion will continue to adversely impact the remnants of the fort.

In addition to fortifications the world’s largest concentration of Civil War shipwrecks are submerged in the waters of Cape Fear. These vessels represent the evolution of ship architecture and construction during the revolutionary transition of ship propulsion from sail to steam, and wood to iron hulls. The material culture remains are evidence of the economic and social impacts to the South during this conflict and their deposition patterns closely reflects the naval boundaries established by Union blockade strategists. The shipwrecks contribute to the history of Fort Fisher, deepening our understanding of the fort as a Confederate stronghold and highlighting the pivotal role it played in the Civil War. There are six wrecks in the New Inlet area of the Cape Fear Civil War Discontiguous Shipwreck District: Arabian, Condor, Modern Greece, Stormy Petrel, USS Aster, and USS Peterhoff. Others are located further offshore or on adjacent beaches like blockade runner CSS Beauregard scuttled in 1863 is still visible at low tide about 100 yards off shore. These wrecks were part of a thesis project for a student participating in the grant initiative. The grant team attempted a reconnaissance snorkel on the site of the shipwreck.

Until its capture by the Union army in 1865, Fort Fisher was the largest earthwork fortification in the world. The “Gibraltar of the South” protected the port of Wilmington and ensured that the Confederacy had at least one “lifeline” until the last few months of the Civil War.

The Department of Geological Sciences installed a seismometer at Fort Fisher. The unit measures ground vibrations and can record the energy of the breaking waves. The objective here is to assess the possibility of using an array to monitor wave breaking, which can enhance an understanding of sediment transport and erosion processes along the coast. A seismic refraction survey was also performed to provide information on the geological framework, which partially controls the vulnerability of a site to erosion processes.

SHIPWRECK DISTRICT AT FORT FISHER

ECU conducted a rapid site assessment of USS Petershoff . The most evident change in the site since a video recorded visit in 2012 was a broken bow area. The wreck is a popular fishing site and it is likely that vessels anchoring on or near the wreck, could damage the structure. Alternatively it could represent structural deterioration, especially the bow area that presents the highest area of relief on the seabed and may lose integrity first. Students noted diagnostic hull features, the condition and marine life including fish and corals. Visibility over a two day period ranged from 1 to 10 feet.

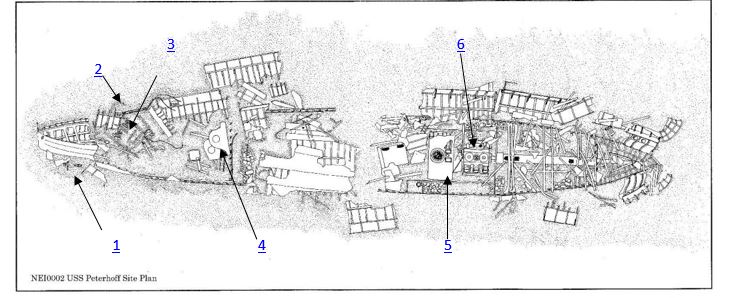

Currently, the wreck is situated within the Fort Fisher Contiguous underwater district and approximately 1.3 miles offshore. It is the wreck furthest out from the coast. The exposed remains of the vessel consist of part of one boiler and a concentration of machinery. The surviving structure has considerable profile and resides on a sand bottom in 34 feet of water. Much of the hull has collapsed, the bow and stern are readily identifiable. The bow lists slightly to starboard and the stern sits on an even keel. Amidships, the engineering space is well defined by the remains of watertight bulkheads fore and aft. Within those bulkheads the boilers and steam engine remain intact. The orientation of the hull is northwest to southeast with the bow to the southeast.

The location of the wreck of Peterhoff was well established at the time of its loss on 6 March 1864. Historical sources confirm that the ship was sunk approximately three miles off the beach three and one half miles southeast of Fort Fisher. Identification of Peterhoff is based on a combination of factors including the wreck location, the surviving hull structure and machinery, U. S. Navy ordnance recovered from the site and the base of a bowl embossed “Peterhoff.” Ordnance recovered from the site by the United States Navy in the 1960s and UAU personnel in 1974 consists of 32-pounder smoothbores, a 30-pounder Parrott rifle and elements of a small boat carriage for a 12-pounder Dahlgren howitzer. All of the ordnance matches the historical inventory of the Peterhoff’s battery. Several additional 32-pounder smoothbores, identified in 1997, remain at the site. The English ironstone bowl base with “Peterhoff” in the bottom provides confirmation of the vessel’s identity.

The overall length of the wreck is sufficient to accommodate the 220 foot length, 29 foot beam and 16 foot 11 inch depth of hold of Peterhoff recorded on the Certificate of British Registry (CBR). The 28 foot beam and 31 foot length of the engine room recorded at the wreck site correspond exactly with those recorded on the CBR. Peterhoff has two engines listed on the CBR and two inverted direct-acting cylinder steam engines were identified in the remains of the vessel. Peterhoff was also known to have a donkey engine and steam powered capstans. The remains of a steam capstan were identified in the wreck aft of the bow adjacent to the anchor davits.

The hull of Peterhoff has broken into two distinct elements. The bow, forward of the coal bunkers, and a stern section containing the engineering space amidships and stern. Most of the 120 foot long forward section of the hull has broken down to the turn of the bilge. A 22 foot section of the bow lies on the bottom listing to starboard and extends more than 10 feet into the water column. That section extends from the stem post to the forward hold bulkhead. A Trotman Patent anchor lies off the port bow and two anchor davits and a steam capstan lie within the surviving hull structure. Aft of the forward hold bulkhead, the hull has collapsed to the turn of the bilge and sections of plate and frames from the sides of the hull lie on the bottom both inside and adjacent to the hull. Deck beams and small sections of the deck clamps lie on the sand within the confines of the surviving lower hull structure.

Peterhoff was originally built by T.R. Oswald for Z.C. Pearson and launched at Sunderland, England in July 1861. The blockade running vessel was captured February 25, 1862, in the West Indies. After condemnation on July 24, 1863, the United States Navy purchased it for $80,000 and re-fitted it as a blockader and re-commissioned it as USS Peterhoff in February 1864, sending it to the North Atlantic blockading squadron and stationed off of New Inlet. On February 20, 1864, Peterhoff was rammed and sunk by USS Monticello, who had mistaken it as a blockade runner.