The wreck is located on an oyster shell beach on Calibogue Sound, Hilton Head. It was part of a South Carolina Underwater Archaeology Division training stewardship course in 2011. At this time, the team sandbagged the timbers to stabilize the shipwreck and prevent it eroding out of the beach. During the 2018 visit, the team observed that the sandbags were scattered and shredded by the wave action.

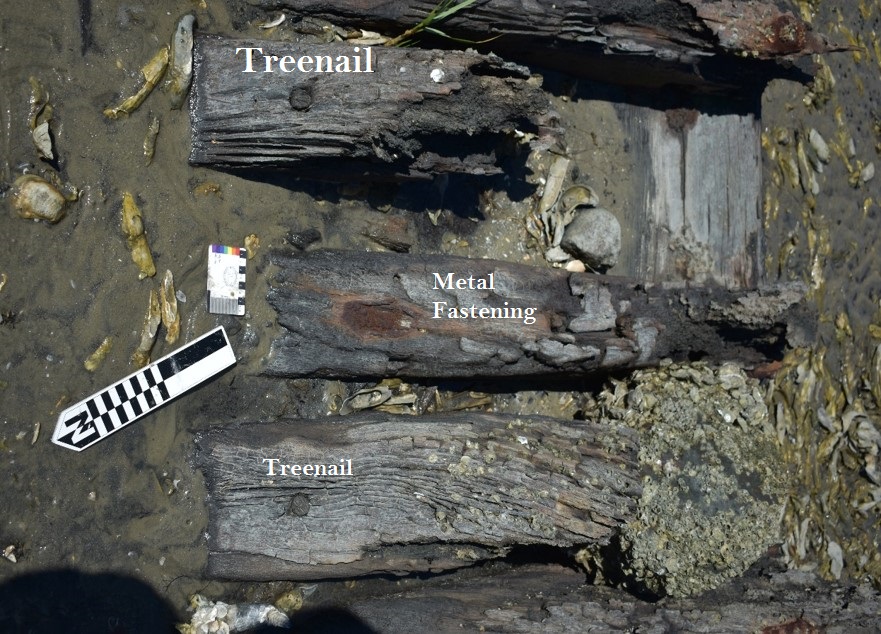

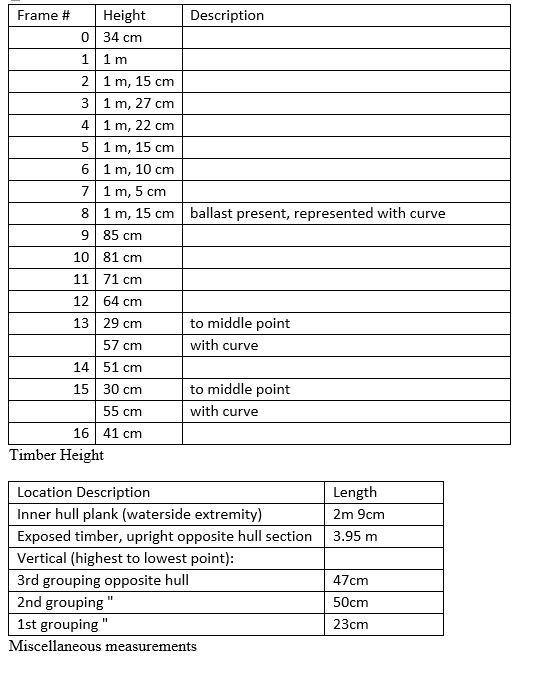

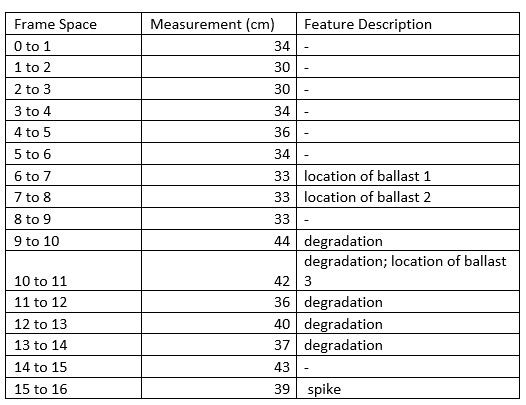

The shipwreck, with an overall length of 13.80m and maximum beam of 4.50m, comprises wood fragments primarily short sections of 17 framing members around 21cm in width and spaced 31 cm apart. The fastenings included both treenails (wooden dowels) and metal spikes. Other timbers were outer and inner hull planking on the wreckage situated higher up on the beach. The site is orientated diagonally to the waters edge. The team observed teredo worm (Teredo navalis, the naval shipworm, is a species of saltwater clam, a marine bivalve mollusc in the family Teredinidae, the shipworms. This species is the type species of the genus Teredo. Like other species in this family, this bivalve is called a shipworm, because it resembles a worm in general appearance) on a few of timbers, especially the frames.

Scattered throughout the Southern eastern seaboard of the United States, shards of different stonewares wash ashore with the ships that originally transported jars and jugs. Plantations used these utilitarian wares for a variety of daily functions. Sometimes these shards also erode out of river banks near plantation sites. Maritime landscapes throughout the South yield a wide array of pottery that reflect both time period and location of these finds. Specifically in South Carolina, the most common type of pottery found is described as Southern Alkaline Glazed Stoneware, which was developed in the early 19th century. Described as “durable, shiny transparent glazes made from a combination of wood ash or lime, clay and a silica source like sand, crushed glass or flint” (Baldwin 1993:1), Southern Alkaline Glazes can be found in a wide array of colors and textures dependent on the mineral makeup, specifically iron, and the kiln conditions that produced them. Continuing until the 20th century, the production of these glazes was centered around Edgefield, South Carolina, spreading south all the way through Texas in the 1840s, and are marked by a rough texture with a smooth drip glaze on the exterior or interior, depending on design specifications (Greer 1970: 161).

Possible Historical Context of the Wreck

Dating to the early 18th or 19th century, the Stoney Baynard Ruins are hidden away in the Sea Pines division of Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, remain the only existing structures of a plantation that once allowed the island to thrive. Originally constructed between 1790 and 1810, Captain John Stoney ran the plantation alongside his two sons, John and James. John specialized in mercantilism out of Charleston, while James worked as a planter. Together, they ran the plantations’ primary crop of sea cotton. Named after Captain Dave Cutler Braddock, owner of the “Beaufort”, the plantation was labored by 129 African slaves during its height of production; Braddock’s Point Plantation was the largest producer of cotton for the area. They owned two schooners named John and Mary and Pick Pockett.

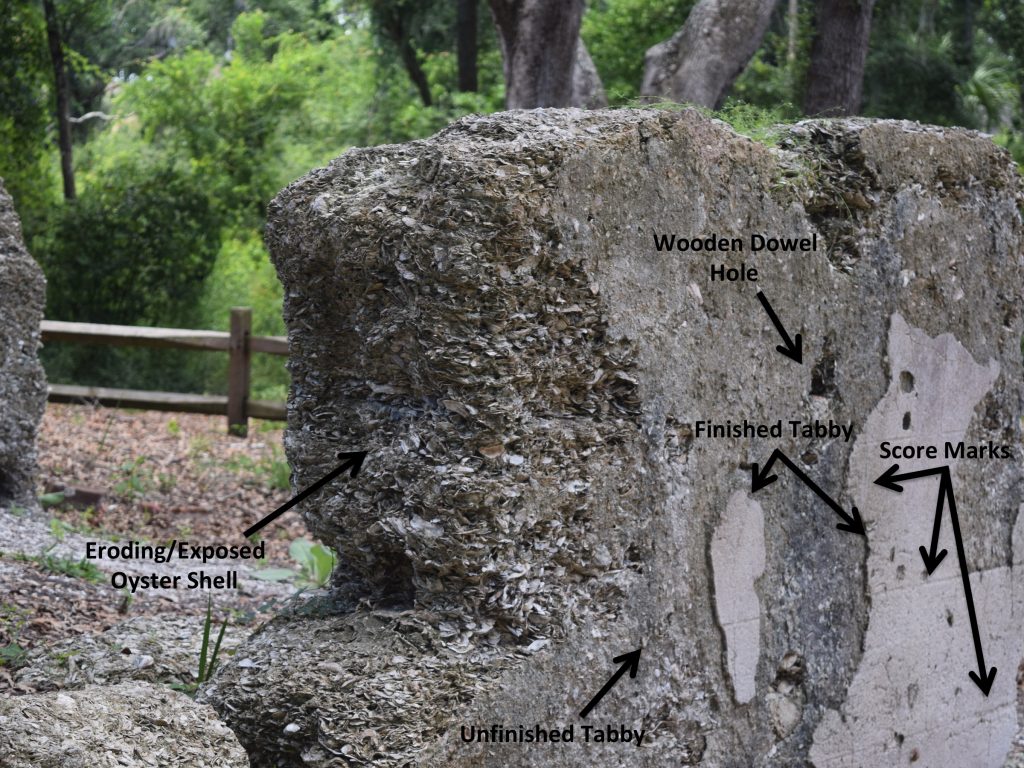

The site today is comprised of the main plantation house side structure, two slave houses, and the kitchen chimney at the furthest end of the plantation grid. Of the 129 slaves on Braddock’s Point Plantation, more than one hundred of them were field hands working to harvest the sea cotton crop day in and day out. The slave dwellings reflect the communal sentiment of the plantation, as it is laid out in almost a street canal, or row, along which other dwelling might have stood. Each dwelling housed two families of slaves, but whose dimensions depicted less than tolerable conditions. Only the tabby style concrete blocks that once supported the wooden structure of the home mark the structure today and give definition to the current conditions of these slave houses. It is interesting to note the overall tabby style used to create these dwellings. Thousands of oyster shells are mixed together to create a concreted block that has stood the test of time, and remain an aesthetic marker for the overall site.

The plantation fell into financial ruin in the early 1830s, and when John Baynard passed away in 1838, the area was sold off to the bank of Charleston to pay outstanding debts. In 1845, William E. Baynard who owned the site until the Civil War purchased the plantation. While not much is known about the involvement of the structures in the Civil War, it is documented that the site housed Union Troops, during which portions of the site were burnt in 1869. Following the Civil War, the structure fell to ruin due to the lack of continued labor previously provided by the slave population of the plantation. Today, the structure lies abandoned and deteriorated amongst an upscale suburban neighborhood at the far end of Hilton Head Island. The overall structures appear deteriorated, but lack evidence of erosion, as each individual oyster shell from the tabby construction can still be observed- a true testament to the history and influence of this structure to the local area.